|

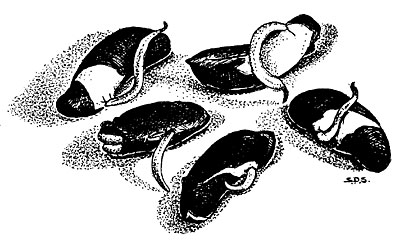

| Sue Szwed drawing |

By Roberta Bailey

Behind every packet of seed is an individual story and an entire history. The story of the seed ranges from an heirloom passed from generation to generation to the hybrid bred for perfect uniformity and ripening. The history of the seed industry is an interwoven tale of small, local seed companies, mail order houses, company buy-outs, of multinational mergers and pharmaceutical companies involved in genetic engineering, and recently of organic seed and a grassroots movement back toward local seed production. A strand of this historic tapestry includes legalities around the seed itself, the establishment and standardization of pure seed levels and germination testing. At one time, what was in the package wasn’t always what the label stated.

In the late 1800s and even into the early 1900s, adulteration of seed was fairly common in Europe and the United States. Sand, screened to the proper size and stained to match, was mixed with clover seed. Cheaper vegetable seed would be mixed with more expensive seed. Often an expensive variety would be mixed with cheaper seed that had been devitalized – treated so that it wouldn’t germinate – thus making it undetectable. England had entire factories for devitalizing seed. Seeds of dodder, a parasitic pest, commonly were mixed with forage crops. In the early 1900s, a survey of vegetable seed sold in stores showed that of 12,454 packets tested, the mean germination rate was 60.5 percent. Mail order packets averaged 77.5 percent.

These unscrupulous practices and more led to the Parliamentary passage of the Adulterated Seed Act in 1869, and in 1897, the U.S. Department of Agriculture published the first rules for standard seed tests for germination, seed purity, weed and inert seed, hard seed and moisture content. In the early 1900s, a group of people from 16 states and Canada organized the Association of Official Seed Analysts, which prepared and adopted uniform methods for testing flowers, vegetables, and forage or field crop seed. To this day, the rules are updated annually and revised every five years.

According to these rules, germination tests must be done every six months on seed being sold commercially. A seed company must have test data on file. The packet must bear the date of the test (i.e. packed for 2003). As a courtesy, some seed companies supply the germination rate and actual test date on the seed packet.

Federally established minimum germination rates for carrots and peppers are 55%, peas and lettuce, 80%; corn, squash, tomatoes, brassicas and beans, 75%; onions, 70%; and eggplant, 60 percent. Seed can be sold with lower germination rates, but this must be stated on the packet, and extra seed often will be added to compensate for the low germination rate.

Germination tests can be done at the seed company or at a seed test laboratory. Small seed companies often test seeds in defunct freezers or refrigerators, because they are well insulated and can be fitted with lights, heat and thermostatic control. Seed is tested at specific temperatures, most often 20 to 30 degrees Celsius (68 to 86 degrees F.). For example, onions are tested at 68 degrees F. The sprouts are counted on the sixth and the tenth day, then the results are added. The actual tests are done between moistened blotter paper or light and dark paper towels. At Fedco Seeds, I use paper towels, loosely rolling 50 to 100 seeds between two towels, depending on the size of the seed. Each test is for 100 seeds (so two towels of larger seeds are used to get the 100 seeds), and we do two replications, then average the two test results.

To determine whether your old seed or home-grown seed is viable, simply count 100 seeds and spread them on one or two moistened but not dripping wet paper towels. Set them in a seed tray or non-reactive container and cover the container with plastic wrap. For cool weather crops, use room temperature, allowing the test to cool to as low as 60 degrees F. at night. Give heat lovers 80 to 85 degrees F. by day and 68 at night. Be sure the seeds don’t overheat, dry out or get too soggy. Very lightly damp towels are best. The seed will be ready to count in a week, although some seed can take a month. A seed sprout is ready to count when the root has emerged and the crook at the base of the cotyledons is visible. If you do a first count partway through the test, remove the sprouted seeds from the toweling as you count them, recording your data. When you count the remaining seed sprouts on their second count, record that data, then add the two counts for your total germination test result. If 90 out of 100 seeds sprout, then the germination rate is 90 percent. If results were poor, vary the test conditions: try darkness, full light, less moisture or more heat.

Some seed, such as sweet peas, vetch and lupine, contain hard seed – seed that has a hard seed coat and does not absorb water in the first flush of germination. It will germinate in a month or a year or whenever the seed coat is sufficiently broken down to allow germination. These seeds are included as part of the final germination percentage. When looking at a test in its final days, these are the obvious, rock hard seeds.

You don’t have to buy all new seed every year. If stored well, seed lasts many years. Pepper and tomato seeds usually last for a mean of six to 10 years; lettuce, three years; carrots, three to six years; corn and beans, three years; brassicas, at least five years; cucurbits, three to five years; and flint or dent corn, 10 years. Seeds of a few species, such as parsnip, parsley, onion, delphinium and larkspur, reputedly don’t last more than one year; if they sprout a second year, overall vigor and performance are reduced.

The ideal storage place for seeds is cool, dry, low in humidity and dark; generally, the sum of the temperature (degrees F.) and relative humidity should be less than 100. Avoiding heat is important, but dryness is key. Store well dried seed in containers that reduce or stop moisture exchange. Glass containers are ideal; heavy plastic containers are good; but plastic bags are quite porous, as is paper. Store seed in glass with desiccant packs (silica, available from Johnny’s Selected Seeds and the Maine Seed Saving Network). Seed can be frozen in glass containers, but avoid frost free freezers, as their temperatures fluctuate too much. When bringing seed out of a freezer, bring the entire unit up to room temperature before opening to avoid condensation.

As a gardener or farmer, you can be assured of a certain quality and purity in the seed that you purchase. With a simple test, you can decide whether to go with what you have left over or purchase fresh seed.

Resources

Ashworth, Suzanne, Seed to Seed, 1991. Seed Saver Publications, RR3, Box 239, Decorah, Iowa 52101, $20.00.

Association of Official Seed Analysts, “The International Rules for Testing Seed,” Journal of Seed Technology, Illinois Dept. of Agriculture, 801 Sangamon Ave., Springfield, IL 62706-1001

Justice, Oren L., “The Science of Seed Testing,” in Seeds, The Yearbook of Agriculture 1961, USDA