|

OSSI Open Source Seed Pledge |

|

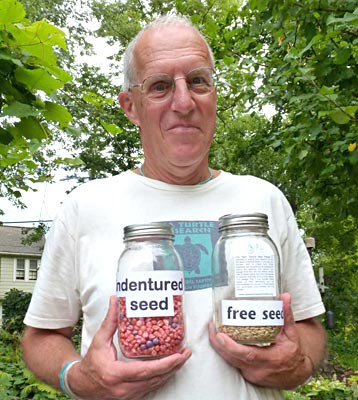

| Jack Kloppenburg, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, has devoted much of his life to seed work. In 1988 he wrote his seminal exposé of the seed business, “First the Seed.” Photo by Claire Luby |

|

| Carol Deppe with the winter squash variety she bred, Sweet Meat-Oregon Homestead. Deppe has pledged this and the other two varieties shown with this article as OSSI varieties. Photo credit: Keane McGee/Nichols Garden Nursery. |

By CR Lawn

The contract arrived this fall from a Fedco supplier of more than 30 years. We had never before gotten anything like this from this family-owned business, considered to be among the “good guys” in the trade. Sitting with them was like stepping back into the ’50s; they personified the very image of old-fashioned integrity.

“Customer shall not reproduce or transfer seed material, nor subject it to any conventional breeding … or any other genetic manipulation techniques … including but not limited to self or cross-pollination reproductions, tissue culture … or transformation techniques. The seed and its genetic material are owned by [xxx] or its licensors and is proprietary material.”

We would pay for this seed but not own it. We would get only a brief, one-time rental. No seed sovereignty here, no independent yeomanry; instead agricultural peonage. Our supplier broke no new ground but merely followed the example set by the Monsantos and Syngentas with their “intellectual property” restrictions.

If one views modern economic history as a dialectical struggle between those who would preserve the commons as a resource shared by all and those who would enclose it for their own private benefit, the recent history of seed provides an object lesson. For generation upon generation, millennia upon millennia, through happenstance, observation and diligence, farmers, as keepers of the seed, saved the best and improved our food crops in a co-evolutionary dance with plants.

Because nature annually regenerates in multiples that would turn any corporate financier green with envy, at first glance seed would seem an unlikely candidate for privatization. Three mechanisms, however, one biological (hybridization), one engineered (genetic engineering) and one legal (patents), have been used to commodify the seed, take it out of farmers’ hands and pass control rapidly to large corporations.

Unlike open-pollinated seeds, hybrid seeds that were developed from disparate inbred lines won’t come true-to-type in the next generation and will require years of arduous re-selection to produce useful, stable varieties. Beginning with sweet corn in the 1930s, the seed industry adopted hybridization, largely because farmers had to repurchase hybrids from the seed company every year; so hybrids, by creating a near-captive market, delivered a larger return on investment for their developers.

In the 1980s genetic engineering upped the ante. Because of its greatly enhanced research and development costs, it catalyzed a vast consolidation of the seed industry. Large corporations bought out smaller players who couldn’t afford to stay in the game.

The Supreme Court in 1980 generated the third stool leg with its 5-4 decision in Diamond vs. Chakrabarty to extend patenting over all aspects of the claimed invention to life forms developed through genetic engineering. In 2001 the court extended these rights to conventional breeding. In the interim, utility patenting has become the gold standard of intellectual property rights.

The Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970 (PVPA) limits protection to the covered variety and permits growers to save and re-plant seeds (but not exchange or sell them) and breeders to use protected seed in their work. Utility patents, however, are absolute, with no seed saving or research exemptions. Beginning with large farm commodity crops, their use has spread widely to lettuce and has begun impacting carrots, onions, broccoli, cauliflower and other garden vegetables. Patents have been applied for “carrots having increased lycopene content” (i.e., very red), broccoli with exserted heads for ease of harvest, lettuce with single-cut salad traits, even “pleasant taste” in melons and “heat stress resistance” in cole crops. Far from being novel, these traits readily appear in nature, or represent minuscule improvements over what is widely available. Internationally renowned plant breeder Frank Morton likens this to “getting a patent on an 18-wheeler when all you did was add a chrome lug nut. It rubs me the wrong way that works of nature can be claimed as the work of individuals.”

Most concerning is its chilling effect on university breeders such as Wisconsin’s Irwin Goldman and Oregon State’s Jim Myers, whose work has been constrained by others’ utility patents. Before the advent of utility patenting, plant breeders were collegial, readily collaborating and sharing germplasm. As Myers puts it, “It’s this collective sharing of material that improves the whole crop over time.” As intellectual property rights fence off more germplasm, the available gene pool for improvement shrinks, increasingly isolating breeders. The original rationale for plant variety protection, to stimulate crop improvement, ironically is stultified.

Now comes a new organization called OSSI, the Open Source Seed Initiative, dedicated to maintaining fair and open access to plant genetic resources worldwide, led by such bioneers as Jack Kloppenburg, Frank Morton, Carol Deppe and Irwin Goldman. As Reich, Warren and Sanders are to those banks “too big to fail,” so Kloppenburg, Morton, Deppe and Goldman are to the corporate stranglehold on the seed supply. At a time of great climatic stress, when diversity is essential to ensure the resilience of agriculture itself, OSSI is racing to secure and enhance the remaining dwindling seed commons.

|

| Renowned plant breeder Frank Morton has pledged his 130 varieties of vegetables, flowers and more to the Open Source Seed Initiative. Photo by Claire Luby |

|

| Irwin Goldman of the University of Wisconsin has had his plant breeding work constrained by others’ utility patents. Here he holds his Badger Flame beet, pledged to OSSI. Photo by Claire Luby |

Kloppenburg, who has devoted much of his life to seed work, is perhaps OSSI’s heart and soul. Now an emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, he came out with his seminal exposé of the seed business in 1988. His choice of title, “First the Seed,” had more than a hint of irony, as that is the motto of ASTA, the American Seed Trade Association. In 1924 pressure by ASTA finally terminated the USDA’s huge, longtime program of free seed distribution of varieties, many from taxpayer-funded breeders at land grant universities. ASTA successfully lobbied for passage of PVPA in 1930 and 1970 and staunchly supports intellectual property rights and genetic engineering.

Inspired by Kloppenburg and alarmed by the growing dominance of genetic engineering over classical plant breeding in our universities, I initiated a two-part series beginning in the 1995 Fedco catalog entitled “Do You Know Where Your Seed Comes From?” Most people didn’t then and many still don’t. Five years later, in another unusual attempt to provide more transparency, I instituted supplier codes in the catalog (https://www.fedcoseeds.com/seeds/catalog_codes.htm). These range from 1 (small seed farmers, including Fedco staff) to 5 (multinationals engaged in genetic engineering) and 6 (manufacturers of neonicotinoids: Bayer and Syngenta).

Morton has pledged his entire oeuvre of 130 varieties of lettuce, mustard, celery, kale, peppers, calendula and more to OSSI. An outspoken opponent of trait and utility patenting in essays in his Wild Garden Seed catalogs, he continues to educate growers and seed people and to illuminate the work of plant breeding.

With her groundbreaking 1993 work “Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties,” Deppe taught and empowered a whole new generation of freelance breeders outside the big universities and seed companies, and inspired many to pledge their varieties to OSSI.

Like wild mushrooms after a warm soaking rain, OSSI-pledged varieties suddenly sprouted in the fertile soil of 2016 editions of some ethically aware seed companies. The OSSI quickly signed up 26 seed company partners and an equal number of plant breeders offering a rapidly growing collection of hundreds of pledged varieties.

The pledge is OSSI’s particular tool for ensuring seed freed from restrictions. Having begun by taking a contractual/legal approach, finding the way obstructed, OSSI changed tack, abandoning courts in favor of moral suasion.

|

| Deppe’s variety Candystick Dessert Delicata is bigger than other delicatas (up to 3 pounds but averaging 1 to 2 pounds); has much thicker flesh; is more vigorous and yields more than other delicatas. “And best of all,” says Deppe, it “has a distinctive flavor that resembles that of a Medjool date. I have no idea how that happened. There were no crosses with Medjool date trees in the breeding. Just one of those happy surprises.” Photo by Carol Deppe/Fertile Valley Seeds |

|

| Cascade Ruby-Gold Flint corn is another of Deppe’s varieties. This very early flint corn has a high yield and superb flavor as cornbread and polenta. “Each ear is solid colored, and every different color gives a completely different flavor of cornbread,” says Deppe, “so you get lots of cornbread flavors from one variety. I believe in corn that is great when fixed simply using basic recipes – not corn that requires a factory and lots of salt, fat and sugar to taste even marginally edible.” Photo by Carol Deppe/Fertile Valley Seeds |

The pledge was inspired by the open source software movement. In an early article about OSSI entitled “Linux for Lettuce,” agricultural writer Lisa Hamilton explained how the copyleft provisions of Linux stood traditional copyright doctrine on its head. Instead of restricting use as a copyright does, the OSSI pledge allows any use whatsoever, provided that the pledge and same freedom be passed on to all future users. Just as Linux encouraged users to create and share improvements, users of OSSI-pledged varieties may freely employ them as breeding material. When applied to germplasm, which, unlike computer software, is alive, the self-perpetuating feature of the pledge creates a viral effect that not only maintains the commons but also potentially expands it by extending coverage to all future varietal derivatives, be they selections or entirely new varieties. This feature of the OSSI pledge extends the public domain by creating a protected commons. Anyone, including Monsanto, can access public domain varieties and breed restricted varieties from them; but Monsanto would not access OSSI-pledged varieties because it could not agree to the pledge. In fact, some of its corn breeders called OSSI seeds “too contagious to touch.”

The pledge permits agreements between seed companies and seed breeders and growers to multiply seed productions and produce seed crops, and allows royalty arrangements between them – essential tools to reward breeders, get their seed into commerce, and remunerate seed companies that coordinate such productions. But OSSI forbids contracts in which obligations are passed on to third parties, thereby ensuring that seed once freed is always freed.

The OSSI is a contra brand, not a seed company. It is about who owns the seeds and what kind of rights they have to them. Its goal is not just to create a reservoir of shared germplasm but also to redistribute power. The OSSI partners are betting that just as a market exists for ethically grown fair trade coffee and chocolate and for organically grown seed, we can develop such a market for freed seed. Ultimately, it is up to you, garden and farm seed buyers, to support such a protected seed commons.

Bibliography

Deppe, Carol, “Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties: The Gardener’s and Farmer’s Guide to Plant Breeding and Seed Saving,” Chelsea Green, 1993, second edition 2000

Hamilton, Lisa M., “Linux for Lettuce” – https://www.vqronline.org/reporting-articles/2014/05/linux-lettuce

Kloppenburg, Jack Ralph Jr., “First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology,” University of Wisconsin Press, 1988, second edition 2004

Morton, Frank, “Holy Crap, You Can Patent That!?” 2013 Wild Garden Seed Catalog, p. 6; “Biology Defies the Nature of Patents,” 2013 Wild Garden Seed Catalog, p. 50; “The Open Source Seed Initiative,” 2015 Wild Garden Seed Catalog, p. 8

Roach, Margaret, Blog: A Way to Garden, Interview of Jack Kloppenburg – https://awaytogarden.com/a-new-brand-of-seed-in-town-ossi-or

About the author: CR Lawn founded Fedco Seeds in 1978 and has worked there since. He recently joined OSSI’s board of directors.