By Holli Cederholm

Making miso is “actually a simple process,” said Nicholas Repenning, while stirring a spoonful of red-brown paste into a mug of warm water. Repenning encouraged a dozen or so students — gathered around stainless steel tables laden with metal mixing bowls, potato mashers, and books on mold-based fermentation — to grab a cup and do the same. “It’s the best way to taste miso,” he continued, recommending a ratio of one tablespoon to 16 ounces of water.

Repenning learned how to make miso — a salty, umami seasoning traditionally made from fermented soybeans and koji, a mold-inoculated substrate — at home with his family and formed a business with Mika Repenning to offer Japanese-style miso to the broader community. For the past 10 years, they have been commercially producing miso, koji, and tamari and selling these products directly from their commercial kitchen in Whitefield, Maine, and to natural food stores as go-en fermented foods. “Go-En is a Japanese word about connection and relationship,” according to the business’s website. “It has an interconnected holistic sense and exists in the convergence of peoples, places, and all events where each has an equal, mutual relationship.”

The website goes on to describe miso as an essential food for Japanese people: one that is made from minimal and simple natural materials, which, when combined, work together in a colony, “creating a balanced harmony.” Rich in essential amino acids, natural enzymes, beneficial microorganisms, and protein, miso is believed to be a healthy part of a diet that promotes a long life.

“It’s a really old food,” Repenning told the students, who were spending a Saturday afternoon in January at MOFGA’s Common Kitchen in Unity, Maine, to learn how to make their own. Miso, he continued, dates back 2,000 years, if not longer. And miso remains a vital part of Japan’s culture today. In 2006, koji was designated as the country’s national mold by the Brewing Society of Japan, which stated that it is “a valuable asset carefully nurtured and used by our ancestors.” Along with playing a critical role in the two-phase fermentation of miso, koji is a key ingredient in other Japanese traditional foods, including sake, rice vinegar, mirin, and soy sauce. Koji, said Repenning, is “responsible for a lot of their culture and the economy.”

In the process of making koji, the spores of a fungus that originated on the rice plant, Aspergillus oryzae, are used to inoculate rice, barley, and/or soybeans. In Whitefield, go-en fermented foods cultivates their own koji, buying A. oryzae spores from a 100-year-old producer in Japan. They steam large batches of Japanese short-grain white rice and, after it cools somewhat, inoculate it with the mold, evenly spreading the grain on white cedar trays they made from locally harvested lumbar. Cedar is known for its antimicrobial properties and their koji room, or koji muro, is paneled with white cedar as well. Repenning refers to it as a “mold sauna,” but they aren’t cultivating just any mold and monitor the conditions to maintain a temperature and humidity conducive to fostering A. oryzae specifically. After two days, the koji is ready. At this point, they either use it to make 50-gallon drums of miso or they dehydrate and package the koji for sale to home-scale miso makers.

In addition to their homegrown koji cultivated with an ancient strain of A. oryzae — a process that Repenning refers to as “farming enzymes” — they put care and consideration into sourcing the other main ingredients of miso: soybeans and salt. go-en fermented foods purchases organic soybeans from New England. For salt, they opt for sea salt, as earth salt harvested from underground deposits can sometimes yield undesirable flavors in fermentation. When making batches of miso for themselves, rather than for sale, they experiment with home-grown soybeans and Maine sea salt, as well as added flavorings like tahini.

As with all fermented foods, microorganisms are critical to the process. “This is about harmonizing,” said Repenning. “It’s taking those bacteria, it’s taking the beneficial ones, it’s excluding the harmful ones.” With miso, koji introduces the necessary enzymes while salt sets the environment to promote the proliferation of desirable microorganisms, certain yeast and bacteria, while limiting the growth of ones that would spoil the food. “Salt is like the bodyguard,” said Repenning.

The flavor of miso can be altered by changing parts of the process, including the ingredients (for example, swapping rice for barley), the concentration of salt, and the duration of fermentation, as well as the fermentation temperature. Sweet miso, for instance, has a lower salt concentration and is aged for a short period of time (usually three to six months). The resulting miso is generally light beige to yellow; the darker the miso is, typically, the older it is.

While some people make miso with beans other than soybeans, such as chickpeas or azuki beans, or by adding other ingredients — think squash, mushrooms, seaweed, garlic, leeks, red peppers, dandelion greens — to result in different flavors, go-en fermented foods sticks to a traditional soy miso, aging it for one year. The result is a rich, dark paste. Repenning, who holds a degree in sculpture and has a background in glassblowing, sees similarities in his work of making flavors. “It’s like any other art form,” he said, “but we’re working with a different set of senses.”

go-en’s Traditional Soy-Rice Miso

250 grams dry soybeans

250 grams fresh or rehydrated koji

100 grams sea salt, plus 10 additional grams

This recipe calls for equal parts dry soybeans and koji, and can be scaled accordingly.

Measure clean organic soybeans and add them to a large pot with cold water to cover. Soak the beans 18-24 hours. (You should be able to split a soaked bean with your fingers and see that the color is uniform all the way through, indicating that the moisture has reached the center. If it isn’t fully saturated, there will be a dry spot, or a darker area, in the center of the bean.)

Next, cook the soybeans for two and a half to three hours in a large pot on the stovetop, or 20 minutes in a pressure cooker. If cooking on the stovetop (which is preferred), skim the soybean skins off as they rise to the top.

The beans will take on 2.24 times their original weight in water. The amount of salt is based on the final weight of the soy plus the weight of the fresh koji, multiplied by 12, to reach a salt content of around 12%. (A one-year miso will have double or more the amount of salt as a quicker fermented sweet miso, which could be closer to 3.5-6%.)

Once the beans can be easily crushed between two fingers, it is time to drain them, reserving 1 cup of the cooking liquid. (The remainder of the cooking liquid can be saved to use in a soup or to water plants.) It is not a big deal if the beans are somewhat overcooked.

Allow the beans to cool slightly, then mash them into a thick paste. This can be done with a potato masher, or other kitchen implement, or by using your hands. A food processer or meat grinder would also work.

Meanwhile, mix the koji and salt (reserving the 10 grams for later) together in a bowl; gently split up any koji clumps with your hands, massaging the salt into the koji to start to break the cell walls. If you are using dehydrated koji, rehydrate with 100 milliliters of water per gram of koji, 30 minutes prior to use.

Once the beans have cooled to below body temperature, add the koji/salt mixture. (The decrease in temperature is important, to avoid harming the enzymes in the koji. But you also don’t want the beans to sit out for very long before introducing the koji and salt, to help exclude bad bacteria.) Massage all three ingredients together with your hands.

At this point, you could also incorporate a small amount of existing miso, similar to adding yogurt to a batch of milk, to introduce a lineage of existing miso microbes.

Next, press the paste into balls the size of tennis balls, to remove air. You can tell if the moisture content is “right” by throwing a ball into a bowl or other empty vessel; it should flatten but stay intact. If it crumbles and falls apart, or even has large cracks, the mixture is too dry. Gradually add some of the reserved cooking liquid as needed, rechecking the consistency. Keep in mind that it is easier to add moisture than to remove it.

Press the balls, one at a time, into a clean fermentation vessel, such as a wide-mouth glass canning jar with a lid. (To first sterilize the vessel, pour in 50% alcohol, coating the vessel and pouring out the liquid. Allow the vessel to air-dry before filling.) You are aiming to compress the paste and reduce air pockets. If you’re using a crock, you can throw the balls into the vessel, rather than pressing them. Leave an inch or so of head space — do not overstuff the vessel — and smooth the surface of the paste. Use a clean, wet towel to wipe the rim to inhibit mold growth. Apply the reserved salt to the top and rub it partially in. Cover the container.

Allow your miso to age for 10 to 12 months at room temperature in a dark place, such as a cabinet or under the sink. The fermentation time will vary with the temperature of the environment, naturally speeding up and slowing down with the seasons. Flavor will deepen with time. However, microbial activity will eventually plateau and the miso might become bitter after two to three years. After the fermentation period, take the finished miso out of the jar and mix thoroughly, then repack the miso and store it in the refrigerator. It can keep years if stored properly (and if you don’t use it all before then!).

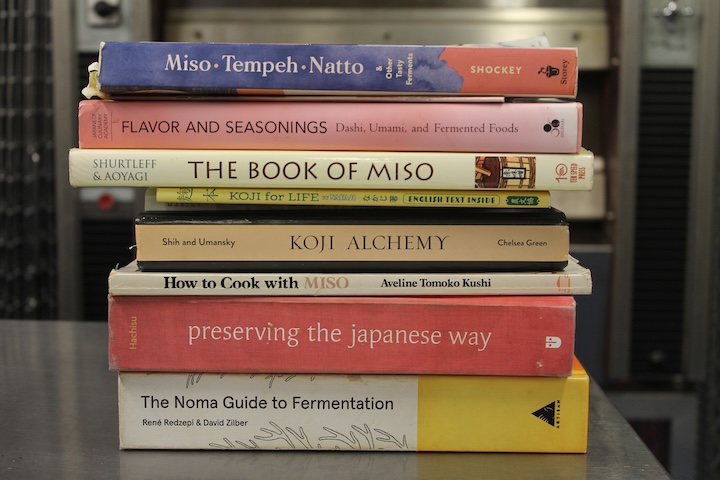

Fermentation Resources

- “The Book of Miso: Savory, High-protein Seasoning” by William Shurtleff

- “Cosy Koji” by Marika Groen

- “Flavor and Seasonings: Dashi, Umami, and Fermented Foods” by Japanese Culinary Academy

- “How to Cook with Miso” by Aveline Tomoko Kushi

- “Koji Alchemy: Rediscovering the Magic of Mold-Based Fermentation” by Rich Shih and Jeremy Umansky

- “The Little Book of Miso Recipes” by South River Miso

- “Miso, Tempeh, Natto, & Other Tasty Ferments: A Step-by-Step Guide to Fermenting Grains and Beans” by Kirsten K. Shockey, Christopher Shockey, and David Zilber

- “The Noma Guide to Fermentation: Including koji, kombuchas, shoyus, misos, vinegars, garums, lacto-ferments, and black fruits and vegetables” by René Redzepi and David Zilber

- “Preserving the Japanese Way: Traditions of Salting, Fermenting, and Pickling for the Modern Kitchen” by Nancy Singleton Hachisu

This article originally appeared in the spring 2025 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.