|

By Roberta R. Bailey

The Common Ground Country Fair is far more than the sum of its tents and activities. It is donkey brays at dawn, manure pitching of presidential magnitude, grass matted down by so many footsteps, cardboard sliding on a hill, the shush of a scythe through oats in a demonstration plot, Sweet Annie artemisia and flowers in a crown, lemonade and yellow jackets; it is the pursuit of garlic to plant, the running crack of a watermelon as the knife starts to cut, peppers roasting in the farmers’ market; it is quiet attention during an herb talk, the tink of a bell on a goat’s neck as it gets herded by a border collie, the whir of a spinning wheel as wool slips through fingers; it is the smiles as the Children’s Garden Parade goes by, the voices coming through the window of the Common Kitchen, a hot cup of cider in chilled hands, a basket of dry beans in which all are encouraged to play, a lamb kebab on a stick, the recycling crew sorting and singing, a ladybug painted on a child’s cheek, a mushroom walk, honey bees working a plot of buckwheat in bloom, and Steve Plumb making his announcements over the PA system.

But for me, and for so many who have come for a few years or 40, the Fair is a weekend-long web of paths crossing. Friends meet friends. Exclamations and hugs follow. People who see each other once a year gather in the center common and play music or share a meal, pulling out some kimchi from home, or a quart of Sungold cherry tomatoes, sharing their favorite apples, passing around a bunch of grapes. Conversation rolls through the successes, the observations, the droughty stretches that made the birds eat more of the blueberries, ripening dates, organic techniques and how they worked this year, stress on the garlic crop, fourth of July tomatoes. It is the shared science of a farming life. It is the Common Ground, the very mycelia of the Fair.

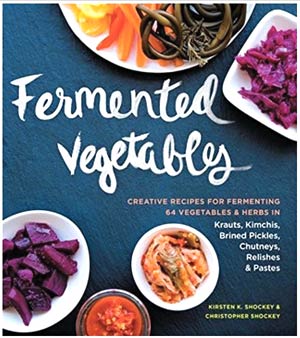

During a lunch gathering at the common last year, I had the best tomatillo salsa I have ever eaten. And I eat a lot of salsa verde. It was fermented, which surprised me and aroused much curiosity. The recipe came from “Fermented Vegetables: Creative Recipes For Fermenting 64 Vegetables & Herbs in Krauts, Kimchis, Brined Pickles, Chutneys, Relishes & Pastes” by Kirsten K. and Christopher Shockey. The book is full of unique recipes that excite and intrigue. I particularly like the herb pastes, such as basil, leek, garlic scape or cilantro paste, as they offer another way to preserve fresh herb flavor in winter. Plus one gets the added probiotic benefits of lacto-fermented foods. Three sections cover techniques on different styles of fermentation. I was informed and reassured by the pictures in the appendix titled SCUM. The fourth section of the book focuses on recipes that use the ferments, including desserts.

Here is a sampling of recipes from “Fermented Vegetables,” all used with the permission of Storey Publishing.

Tomatillo Salsa

(A quick condiment to be eaten within a few weeks or over the entire winter. For a more developed acidic flavor with a wonderful lemon-vinegar quality, allow this vinegar to ferment for 3 weeks or more.)

Yield: about 1 quart.

1 pound tomatillos, husked and washed

1 medium onion, diced

1/2 to 1 c. cilantro

2 cloves garlic, minced

juice of 1 lime (for extra lime flavor include the zest)

1 to 3 jalapenos, diced (optional); include seeds for more heat

1 tsp. unrefined sea salt

Remove the husks from the tomatillos; rinse the fruit well in cold water. Dice the tomatillos and put them in a bowl. Add the onion, cilantro, garlic, lime juice, pepper and jalapenos, if using. Sprinkle in the salt, working it in with your hands. Taste and add more salt as needed to achieve a salty flavor that is not overwhelming.

The brine will release quickly. Press the salsa into a jar. More brine will release at this stage and you should see brine above the veggies. Top the ferment with a quart-sized Ziploc bag. Press the plastic down onto the top of the ferment and then fill the bag with water and seal; this will act as a weight to keep all below brine level.

Set aside on a cookie sheet to ferment, someplace cool and out of direct sunlight, for 3 to 21 days. Check regularly to make sure the vegetables stay submerged.

You can start to test the ferment from day 5 onward. The onions will retain a fresh crispness while the rest of the vegetables will soften.

Store in jars with lids tightened, in the fridge, leaving as little headroom as possible and tamping the ferment below the brine level. The shorter ferment should be eaten within a few weeks; the longer ferment will keep, refrigerated, up to 6 months.

Cranberry Relish

Yield: about 1 quart

2 oranges

16 oz. fresh cranberries

1/2 tsp. unrefined sea salt

1 c. fruit-juice-sweetened, dried cranberries

1 Tbsp. chopped candied ginger (optional)

Wash the oranges and zest one of them. Peel and section both oranges, then remove the membranes from the sections. Chop the sections and set aside.

Wash the cranberries and put them in a food processor. Pulse until lightly chopped. Transfer to a bowl and massage in the salt for a minute to develop the brine. Then mix in the dried cranberries, orange zest and sections, and add ginger, if using.

Press the mixture into a small crock or jar, eliminating air pockets. The brine will be a little thick from the oranges. Top the ferment with an open quart-sized Ziploc bag. Press the plastic down onto the top of the ferment, then fill it with water and seal. This will weigh the food down, below the brine.

Set aside on a baking sheet or in a pan, out of sunlight and in a cool place, for 5 to 7 days. Check daily to see that the fruits are submerged, pressing down as needed to bring the brine to the surface. Taste on day five. It will be deep crimson and have sour notes of cranberry and lacto-fermentation.

Store in jars with lids tightened, in the fridge, leaving as little headroom as possible, and tamping the relish below the brine. This ferment will keep, refrigerated, for 6 months.

Basil Paste

You can use leaves and some soft stems, but not flowers, as they impart a bitter taste. Add this paste at the end of your cooking time to sauces or soups, or use in salad dressings.

Any quantity of leaves, in 1/4-pound bunches

1/4 tsp. unrefined sea salt per bunch

Place leaves and non-woody stems in the food processor and pulse to make a paste. Sprinkle in the salt. The herbs will become juicy immediately. Press the herbs into a small jar. More brine should release at this stage, and you should see brine above the vegetables. Top the ferment with a plastic bag as for the Cranberry Relish (above).

Set aside for 4 to 10 days. Start to taste at 4 days. It is ready when the ferment has a pickle-y taste and a full herbal bouquet.

Store in jars in the fridge. Pack the jars with little headroom and brine above the basil paste. Keeps refrigerated up to 1 year.

Carrot Kraut

Yield:1 gallon

RB’s note: I eat this ferment tossed with winter greens as a bright and delicious salad.

Note: Due to the high sugar content of carrots, this kraut will continue to work in the fridge and will become increasingly sour with time.

8 lbs. carrots, peeled if needed, or scrubbed

1 to 2 Tbsp. grated fresh ginger

juice and zest of one lemon

1-1/2 to 2 Tbsp. unrefined sea salt

Combine the carrots, lemon juice, zest and ginger in a bowl. Add 1-1/2 Tbsp. salt, and, with your hands, massage into the veggies, then taste. They should be salty without being overwhelming. Add more salt if necessary. Liquid will begin to pool.

Transfer the mixture to a 1-gallon crock or jar, a few handfuls at a time and pressing down with your fist or a tamper to remove air pockets. Brine should be seen on top of the carrots. Fill a jar to within 2 to 3 inches of the top and a crock to 4 inches headspace.

Cover the carrots with a piece of plastic wrap or other primary follower (see book). For a crock, cover the carrots with a well fitted plate, then weigh down with a sealed, water-filled plastic bag. For a jar, use a water-filled plastic bag. Ferment 7 to 14 days in a cool, dark place on a baking sheet or in a pan. Taste at 7 days. It is ready when it has a crisp-sour flavor and the brine is thick and rich.

When it is ready, transfer the carrot to smaller jars and tamp down. Pour in any brine that is left. Cover and store in the fridge. Keeps 6 to 12 months but is best eaten in first 6 months.