By MOFGA Crop Specialist, Caleb P. Goossen, Ph.D.

Today there are many more plant disease management products available to organic growers than in decades past, but it continues to be difficult for me to confidently recommend some of the newer products as “worth it” — especially when I’m talking with commercial growers that are relying on a crop for their livelihood — as these new materials are often considerably more expensive than the oldest, and most tried and true materials, namely copper and sulfur. The efficacy data from research trials using these newer products is oftentimes limited and inconsistent. With this in mind, I conducted a trial of fungicides approved for organic use on winter squash at the MOFGA Common Ground Education Center in Unity, Maine, during the 2023 growing season.

Fungicides Trialed

While both copper and sulfur fungicides can easily be used very safely, there are some organic farmers and gardeners who want disease management options that are even lower risk, as copper can be harmful to aquatic wildlife, and while an essential trace mineral in the human diet it is toxic at very rare high levels. This trial included Disperss (sulfur) and Kocide 3000-O (copper hydroxide) as “standard practice” treatments, though there are several other brands of similar products.

Among the fungicides trialed was Regalia, one of the better known and perhaps “oldest of the newer” materials. It is made of an extract of giant knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis, a cousin to the Japanese knotweed often found in Maine) and works by stimulating plants’ innate defense systems — such as growing a thicker cuticle that will be harder for disease organisms to penetrate.

Another material I have seen in use on some farms, called Thyme Guard, has thyme oil as its active ingredient. Thyme oil is considered a “minimum risk pesticide” by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which exempts it from normal EPA registration and regulations. As such, I have to admit that I held a bias that it likely was not very effective. That suspicion was part of my motivation for performing this trial — I wanted to know if I could confidently say “don’t bother” or if I had to reconsider its potential usefulness.

What seem to be the bulk of new disease management products, however, are bacterial-based bio-fungicides. There are many different strains of bacteria, and their extracts, that have been commercialized — and in this arena of bacterial-based bio-fungicides there are far too many new products to be able to trial them all, so I chose one to trial, named Stargus, and decided to give it its best chance for success by also including it in concert with other products.

We tested the fungicides on Honey Boat delicata squash, a crop and variety that is susceptible to foliar diseases (powdery mildew in particular), which we planted densely — two plants every 36 inches in-row — in order to best create the conditions needed to test the efficacy of the fungicides. Each fungicide treatment was randomly assigned to four identical plots — called replications — to allow for statistical analysis of the results. We applied the chosen fungicides (see Table 1) on July 21, August 5, August 10, and August 24.

| Product Name | Product Class | Active Ingredient | Rate Applied | Cost Per Application | Notes |

| Disperss | mineral/synthetic | sulfur | 5 pounds/acre | $5.50 | Active ingredient historically recommended by MOFGA staff for powdery mildew on squash, among the best demonstrated efficacy against powdery mildew. Limitations for use in hot weather conditions. |

| Thyme Guard | botanical/essential oil | thyme oil | 1 pint/acre | $14.58 | Exempt from EPA pesticide registration and of interest to many growers — largely the inspiration for this trial, as its efficacy is not well documented. |

| Kocide 3000-O | mineral/synthetic | copper hydroxide | 0.5 pound/acre | $5.40 | Typically an effective general- purpose fungicide allowed in organic production. Some producers avoid using copper, due to potential environmental and health impacts. |

| Regalia | botanical | Giant knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis) extract | 1.6 quarts/acre | $28.48 | A well-known bio-fungicide that works by stimulating plant defenses. Has shown some partial efficacy against powdery mildew in past research by others. |

| Stargus | bacterial | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain F727 cells and spent fermentation media | 1.6 quarts/acre | $28.00 | Manufacturer representative suggested their best bio-fungicide for general foliar diseases. Many growers are interested, but efficacy is not well documented. |

| Stargus + Disperss | combination/tank mix | combination/tank mix | 1.6 quarts + 5 pounds/acre | $33.50 | An attempt to combine sulfur’s known efficacy in controlling powdery mildew with Stargus’s help preventing other foliar diseases. |

| Stargus + Regalia | combination/tank mix | combination/tank mix | 1.6 quarts + 1.6 quarts/acre | $56.48 | Manufacturer recommendation for control of powdery mildew and other foliar diseases (both products from same manufacturer). |

Table 1. Fungicides trialed, and their cost per application, calculated on a per acre basis from 2022 prices.

The Experiment and Results

The overall experimental approach was to both maximize the potential for foliar disease development by means of cultural practices (i.e., variety selection, planting density) while simultaneously attempting to give the fungicide products their best opportunity at showing efficacy by applying them “early and often” relative to common farmer practices. Unfortunately, the unprecedented rainy conditions of 2023 may have increased environmental suitability for foliar disease proliferation in the trial, therefore limiting fungicide efficacy. Two foliar diseases of squash, squash anthracnose and cucurbit powdery mildew, were observed at the last spraying date, August 24, with anthracnose having killed enough foliage to initiate the trial’s harvest on September 7 (winter squash need to be harvested when there is no longer a leaf canopy to shade fruit from the sun). That being said, marketable yield from each plot (measuring 24 row feet in length) was 41.46 squash fruit weighing just over 1 pound each on average; this equated to 12,541 fruit on a per acre basis, with a total marketable yield of 12,867 pounds per acre, which is more than 50% greater than the New England five-year average of 7,940 pounds per acre. This gives us confidence that the results of the trial are applicable to the same real-world farming conditions of the farmers served by MOFGA’s farmer programs.

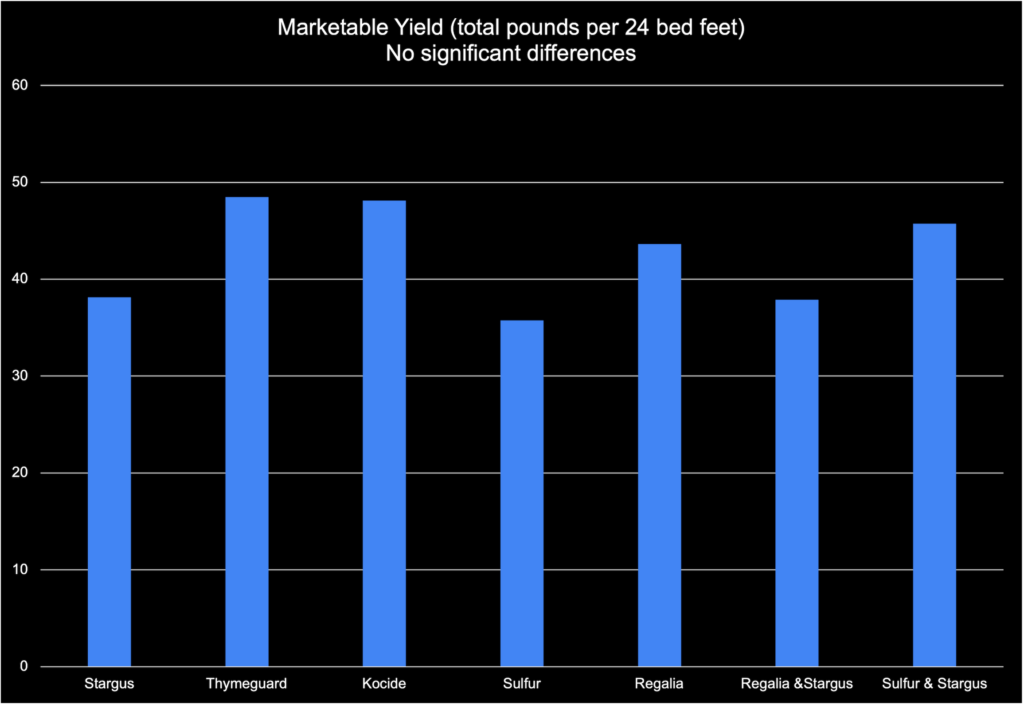

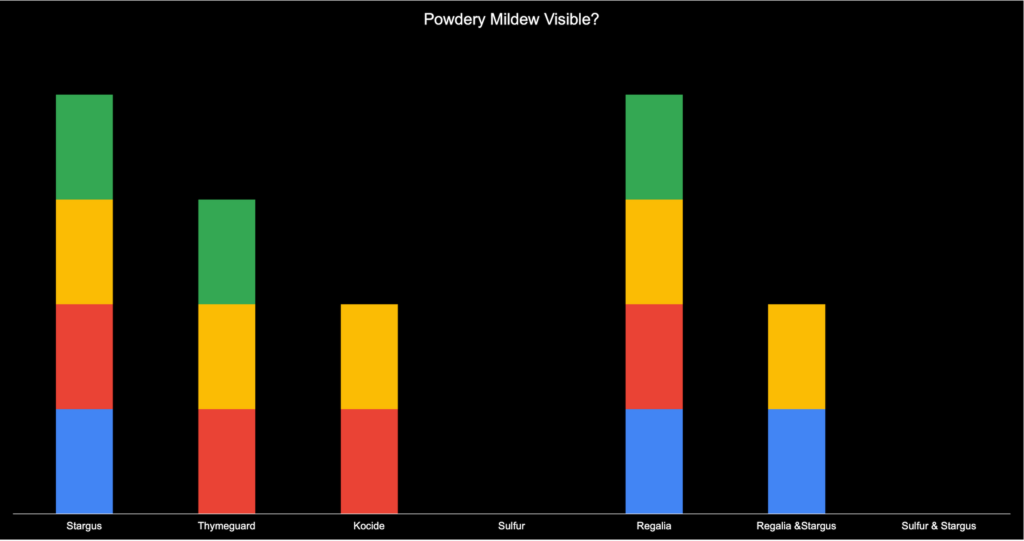

Marketable yields, and the number of fruit per plot, were not statistically different between fungicide treatments (Fig. 1). In other words, the yield differences between plots receiving different fungicides were not large enough in comparison to the differences between replicated plots receiving the same fungicide to indicate that those differences were due to anything other than random chance. The presence or absence of powdery mildew, however, was statistically different between the fungicide treatments (Fig. 2). Powdery mildew was not visible on any of the plots treated with sulfur alone or with a combination of sulfur and Stargus, though both of those treatments were only statistically different than Regalia- or Stargus-only plots, which were the only treatments to show powdery mildew in all four replications. This finding aligned with my standard recommendation of sulfur for control of powdery mildew in cucurbits.

The only other statistically significant difference between the treatments was a visual foliage health assessment, performed on September 2, five days before the harvest data was collected. This was driven by the contrast between the treatment with the healthiest foliage, copper, and the treatment with the poorest foliage health score, sulfur. While this may seem contradictory to the finding regarding powdery mildew presence, the historically wet growing season of 2023 (the second wettest June-July-August period on record for Maine) was not conducive to the progression of powdery mildew and was instead much more conducive to the spread and development of squash anthracnose.

Squash was chosen for this trial because its odds of becoming infected with powdery mildew by harvest is typically considered “a sure bet,” and therefore these fungicides would be given at least some opportunity to show their efficacy against one or more diseases. In practice, many farms choose not to spray for squash foliage diseases, except perhaps in a year when powdery mildew presence begins early and is threatening to defoliate the protective crop canopy before fruit have reached full maturity. Our results, which show no statistically significant marketable yield differences between treatments, suggest that these fungicides may not make financial sense to apply to winter squash in many, if not most, years. While the design of the trial only allows for some conservative interpretations of the statistically significant differences, the overall direction of the results suggests that sulfur treatments continue to be the most useful in a “normal” growing season that favors powdery mildew, while copper continues to be the “gold standard” in terms of efficacy against other foliar diseases. Had the overall trial not needed to be harvested at the same time, copper plots, which showed healthier foliage, may have been able to produce a greater marketable yield or more fully mature fruit with greater long-term storage potential if harvested later. Anecdotally, thyme oil plots looked much better than had been anticipated. While we now have much better footing to urge grower caution when choosing the most expensive bio-fungicides, thyme oil products may warrant further investigation as potential options for growers that are looking for alternatives to copper and/or sulfur products, despite those products’ affordability and seemingly continued outperformance of many bio-fungicides in many situations.

It is important to mention the limitations of these results. This was only one small trial of some products, at single application rates, on one variety of one crop. Crop diseases vary in their infective potential every year, and it continues to be difficult to extrapolate findings from any one trial to other potential use cases. The variety selected for this trial exhibited significant genetic diversity — while this is often a good thing in the long term, it undoubtedly added variability to the trial’s yield results, making it more difficult to distinguish impacts of fungicide treatments. Additionally, we did not leave any untreated plots as a control for comparison, meaning that we cannot say that any of these treatments provided a better outcome than doing nothing at all (and the associated labor and material cost savings of doing nothing!).

Special thanks to The Peter Alfond Foundation, Foundation For Sustainability and Innovation, and the Evergreen Foundation for their support of this trial, and Jack Kertesz, Joshua Pavese, Jake Ressel, Marta Łaszkiewicz, and C.J. Walke for assistance in planting, maintaining, and harvesting the trial.

This article was originally published in the fall 2024 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. Browse the archives for free content on organic agriculture and sustainable living practices. Subscribe to the publication by becoming a member!