|

By Eric Sideman, Ph.D.

As everyone knows, last summer was wet and late blight was widespread on farms and in gardens. Some of you may be tired of hearing about it, but whether the crisis repeats in 2010 depends greatly on the weather and on what gardeners and farmers do to prevent the disease.

I have repeatedly stressed that understanding the biology of the organism that causes the disease is the first step in avoiding it. Late blight is caused by a fungus with great similarity to some algae, which helps explain why it needs lots of moisture to do well. The fungus is called Phytophthora infestans, which may sound familiar to those who remember history, because this organism was responsible for widespread potato problems in Ireland in the mid-1800s. Late blight occurs regularly in Maine, but usually it is spotty and not severe – and usually it does not affect tomatoes. Let’s look at what differed in 2009, and what can we do in 2010.

Life Cycle

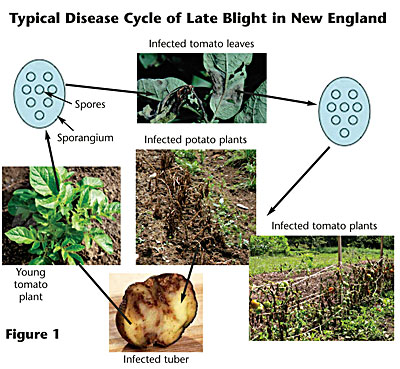

In the typical life history of late blight in Maine (Figure 1), the pathogen persists from year to year only in potato tubers and usually spreads from sprouting tubers in cull piles; from volunteer potato sprouts from culls left in the garden or field while harvesting; and, less commonly, from planting diseased seed. The diagram shows that when diseased potato pieces sprout in the spring, the young plant carries the disease, which eventually releases sporangia (spore-containing structures). These sporangia land on new potato or tomato leaves, germinate and infect the new plant, and then this diseased plant produces more sporangia that infect more plants.

The sporangia can blow in the wind for 50 miles. If conditions are damp and cool, late blight can spread fast and far.

Usually conditions are not right. The spores are actually quite wimpy and die within hours in sunlight or dry conditions. We had very little sunlight and dry conditions the first half of last summer, so late blight spread like wildfire.

[Note that two mating types, A1 and A2, are required for sexual reproduction of the late blight fungus. So far in Maine and in most of the United States, only one mating type occurs at a time in any location. For more than a decade, only mating type A2 has been found in Maine. Both occur together in Mexico. Let’s hope both never occur together in Maine. When both do occur together, sexual reproduction takes place, producing a different kind of spore (an oospore) that is very hardy and resistant to drying, cold, heat, etc.]

|

| Figure 2: Many growers had to bury or otherwise dispose of diseased tomato plants last summer. Sideman photo. |

Big Bad Big Box Supplier

The other way that last summer differed from most others and led to calamity was the source of spores. Usually late blight arises when farmers and gardeners mishandle potato tubers, but last year most late blight in Maine came from tomato seedlings brought into the state from a large producer in Alabama.

Nearly all big box stores in the Northeast get tomato seedlings that they sell to gardeners from the same producer. This large producer sends 1-inch plugs (small plants) to one or the other of two greenhouses in Maine or New Hampshire to be raised to salable size and then shipped to big box stores. This year these plugs came to Maine and New Hampshire already infected with late blight.

By the end of June, we were already finding infected tomato and potato plants in gardens and on farms in New York, New Hampshire, southern Maine, etc. By midsummer nearly every town was reporting late blight.

Interestingly, late blight in the potato growing region of Maine (The County) was no different than in an average year. It was the same strain (US 8) of Phytophthora infestans that commonly appears there, and it was managed well. The southern half of Maine (as well as New York, New Hampshire, etc.), however, had a different strain, US 14/17 – the same strain that was on the tomato seedlings.

|

| Figure 3: The strain of late blight that hit Maine last summer was much more virulent on tomatoes than potatoes. |

Hoping to contain the spread last summer, MOFGA quickly recommended that growers and gardeners pull and destroy infected plants in order to reduce the number of windblown spores infecting other farms and gardens. Many followed our guidelines. Gardeners bagged plants and took them to the dump; farmers dug large graves for their diseased tomato plants (Figure 2).

Controls

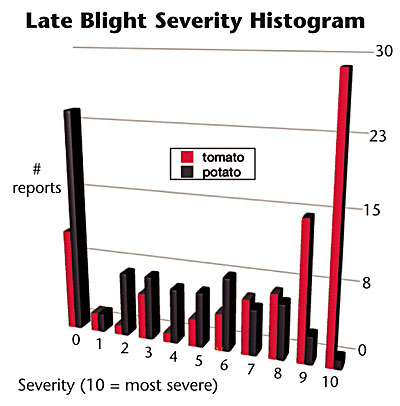

In the fall, when the grieving was over, I surveyed all MOFGA farmers about late blight and received more than 100 responses. Figure 3 shows the number of growers reporting damage on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being most severe. The survey clearly showed that this strain of late blight is much more virulent on tomatoes than potatoes. The typical strain we see in Maine is the opposite. I almost never see late blight in tomatoes.

Another difference about this strain from Alabama is that the warm weather we finally got late last summer took awhile to slow the spread. The typical US 8 strain that we normally see in The County is stopped in its tracks by warm weather.

My survey also asked about control materials. The only clear information I got was that growers who began spraying early with an organically approved copper product and sprayed weekly all season escaped major loss. Some other people reported some success with other products, such as Serenade, Sonata, Oxidate and Actinovate, but for each product reported as successful, I had other reports that that product did not work. To read about a trial comparing organic materials, see https://ospud.orgmaterials_for_late_blight_management, which reports the same results as my survey: that copper was the only really effective material.

|

| Figures 4 and 5: Tomato and potato varieties differed in susceptibility to late blight – although some varieties did better on some farms and than others. |

|

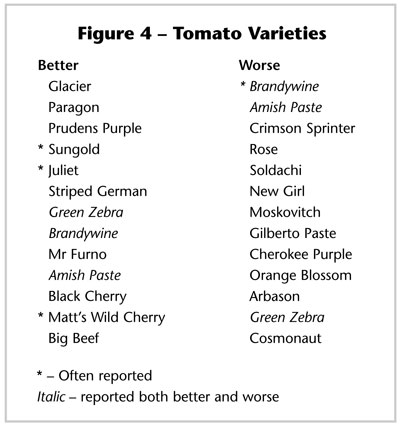

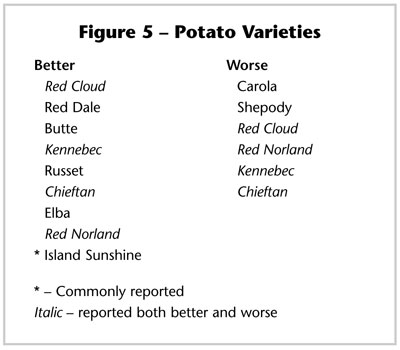

I also asked which varieties were more or less tolerant. Figures 4 and 5 show some conflicting reports, but a few tomato and potato varieties seem promising.

What about next year? The late blight fungus is an obligate parasite, i.e., it survives only on living tissue. In the Northeast, very little plant tissue survives the winter. Except in greenhouses, only potato tubers live through winter. Since the spores are wimpy, growers need only pay attention to managing potato tubers. If all growers adhere to the following steps, we should avoid the strain of late blight that invaded us from the south last year (assuming seedlings from Alabama are clean).

1. Do not keep cull piles of potatoes.

2. Do not save questionable potato seed.

3. Do not compost diseased tubers, because parts of the compost pile may not be hot enough to kill the tubers but may be warm enough so that the tubers don’t freeze in the winter, providing the pathogen with living tissue for overwintering.

4. Buy seed from a good source.

5. In the spring, scout, pull and destroy all volunteer potatoes.

People often ask me if they should clean tomato cages and whether tomato seed carries late blight. I recommend cleaning cages, stakes, etc., but not for late blight. Late blight will not survive there because all the plant tissue on the cages is dead; but other common tomato diseases do survive, so yes, clean the cages.

Here’s the good news: Late blight is not carried on tomato seed.

Eric Sideman is MOFGA’s organic crops specialist. You can address your questions to him at 568-4142 or [email protected].