| The OMRI categories that may include pesticides are: amino acids Bacillus thuringiensis Beauveria bassiana biological controls boric acid botanical pesticides calcium polysulfide copper products corn gluten diatomaceous earth enzymes nonsynthetic fungicides gibberellic acid nonsynthetic herbicides hydrogen peroxide inoculants lime sulfur limonene neem cake and extract nonsynthetic nematicides narrow range oils nonsynthetic oils pheromones potassium bicarbonate pseudomonas pyrethrum animal repellents seed treatments soap spinosad sulfur trichoderma virus sprays |

By Jean English

Thinking of trying a new, home-brewed, organic insecticide on a crop that you’ll be offering for sale? Think again: If a product is used as a pesticide on a crop that is to be sold, you could be violating the federal food safety law.

This was just one eye-opening point that Gary Fish of the Maine Board of Pesticides Control (BPC) staff made at a MOFGA-sponsored talk at the Agricultural Trades Show in January. Other important points included adhering to Worker Protection Standards and keeping records of all pesticide applications.

Pesticides

Fish pointed out that 21.6% of the products listed by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) are pesticides, ranging from organically-approved formulations of Bt to copper hydroxide. A pesticide, said Fish, is defined as any substance or mixture of substances intended to prevent, destroy, repel or mitigate any pest; or any plant regulator, defoliant or desiccant.

Fertilizers or nutrients are not considered pesticides, but disinfectants, bleaches, herbicides, rat and mouse baits and fungicides are, as are insecticides, botanicals, biological controls, and paints, stains and duct cleaners.

Compost tea and manure tea may be included as well, depending on how they’re advertised. “If the sales pitch or intended use is to control diseases, then they are pesticides and need to be registered as such,” Fish explained.

Other substances listed by the USDA’s National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) that are pesticides include:

chlorine materials

calcium and sodium hypochlorite

copper sulfate

peracetic acid

sulfur dioxide

vitamin D3

potassium bicarbonate

streptomycin

tetracycline

ethylene gas

The laws regulating pesticides include federal EPA FIFRA laws and regulations; and state BPC Title 7 and Title 22 laws and regulations. “Maine, like most states, has stricter regulations that the federal EPA,” said Fish. “You [organic growers] come under the same rules as conventional agriculture.” Growers can contact the BPC to get a book of Maine pesticide laws and a book of rules that the BPC has put together.

The BPC

Fish explained that the BPC consists of seven public members appointed by the Governor: two general public members with demonstrated interest in environmental protection (Lee Humphreys and Clyde Walton); one medical doctor (Carol Eckert); one agronomist or entomologist from the University of Maine (John Jemison); one forestry specialist (Michael Dann, soon to be replaced by Dan Simonds); one commercial applicator (Andrew Berry); and one private applicator/grower (Seth Bradstreet III).

The major BPC programs that affect organic growers are:

• pesticide registration: “If it is not registered in the state, it’s illegal to use;”

• Worker Protection Standard: “It impacts you if you have employees;”

• Enforcement, i.e., looking for violations and responding to complaints.

Licensing – another BPC program – “generally doesn’t apply to organic growers because they don’t use Restricted Use pesticides.”

Pesticides, Fish continued, must be registered by both the EPA and the BPC to be used in Maine, with a few exceptions. Essential oils and other food grade products that are used as pesticides are not registered by the EPA any more, but the BPC still registers them.

Fish reviewed pesticide labels, which are legal documents that provide directions for mixing, applying, storing and disposing of pesticides. “Users must comply with all instructions on the pesticide label.”

Classes of Pesticides

Three classes of pesticide include General, Restricted and Limited Use. The General Use pesticides are lower risk products that are available over-the-counter. “You don’t need a license to purchase and apply these, with a few exceptions, such as Velpar [not used by organic growers], because it has been found in ground water; and all aquatic herbicides.” Restricted Use pesticides are higher in risk and are available only at licensed dealerships for purchase by licensed applicators. And Limited Use are higher risk yet, available only by special permits.

In licensing pesticides, the risks and benefits are weighed, continued Fish. Risks “have been given much more weight since the Food Quality Protection Act, except for microbials, such as things that help prevent public health problems.” He added that risk is a product of toxicity and exposure, and that the BPC mantra is to minimize both. “One of my concerns for organic growers,” Fish pointed out, “is if they are using a low toxicity product but are exposed to it regularly. We assume you’ll run into problems.” He emphasized that some organic pesticides have lower LD50s (the lethal dose required to kill 50 percent of test animals) than some synthetic pesticides.

Regarding homemade remedies, Fish said that if you make and use them yourself on crops for your own consumption, they do not have to be registered. However, if you use one on a crop for sale, that’s a gray area. “It’s probably a violation of law, but I don’t see it being enforced soon.”

Pesticide labels contain signal words that indicate their risk:

• ‘Caution’ is the lowest hazard;

• ‘Warning’ means moderate hazard;

• ‘Danger’ indicates a higher hazard.

• ‘Danger Poison’ with a skull-and-crossbones represents an even higher toxicity and is used for products such as Temik and Guthion. These ratings are based on whether products cause irreversible eye damage, skin burns, or “how readily they may kill you.”

Labels tell how to reduce risk, by wearing protective clothing, for instance. Gloves and eye protection are required for all pesticides; others require more.

EPA’s Worker Protection Standard

Fish explained the EPA’s Worker Protection Standard (WPS) that was passed in 1992 and fully enforceable in 1994. This Standard is intended to protect people who work with or around pesticides and includes all commercial products used on agricultural plants, in research, on the farm, in forests, nurseries and greenhouses. It exempts products used on animals but not crops grown for animals.

The Standard applies to agricultural workers and pesticide handlers who are not family members. These employees must be trained, and employers bear the primary responsibility for compliance with the Standard, while labor contractors bear joint responsibility. Compliance includes a central information display about the safe use of pesticides; pesticide safety training; emergency assistance; and decontamination materials. The Standard defines the need to notify workers about pesticide applications, how to protect themselves, and what re-entry times are required. It tells handlers about protective equipment and other aspects of safe handling. Farm owners and their families are exempt from WPS training, because the owners are expected to protect themselves and their families.

Drift Regulations

Fish covered drift regulations, which apply only to powered applications and require applicators to minimize drift to the maximum extent practicable. “But,” Fish emphasized, “drift can be a problem with any type of application, even granular or nonpowered sprays.” Drift regulations require that applicators must identify, record and map sensitive areas within 500 feet of the target site edge. Sensitive areas include homes, businesses, etc.; athletic fields; recreational areas; crop or livestock areas; and wetlands and other bodies of water. Applicators must calibrate equipment and note the wind speed, not spraying when the wind exceeds 15 mph, which “is incredibly generous,” Fish believes.

Violations are evident when residues exceed 20% of the concentration applied to the target crop; when sensitive crops are damaged; when drift causes certified organic crops to fail to meet acceptable residue standards; and when pesticides drift onto people or animals.

If neighbors within 500 feet request, they must be notified when pesticides are to be applied.

They must be told the approximate date of the application; the pesticide(s) to be applied and how they’ll be applied; and the name of a contact person for additional information.

Water Quality Protection

Standards for water quality protection require that pesticides not be mixed or loaded within 50 feet of surface water; that water pumping systems must have anti-siphon devices; that pesticides must be secured on vehicles; and that spills be cleaned up immediately.

|

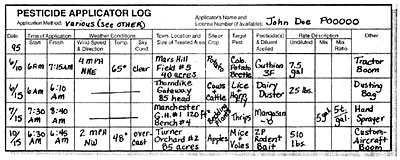

| Sample pesticide applicator log. |

Record Keeping

Regarding record keeping, Fish said that all commercial agricultural producers must keep records of all pesticide applications, and defined a commercial agricultural producer as anyone who tries to make money producing plants, animals or animal products. Use of general, restricted and limited use pesticides must be recorded, whether powered or nonpowered applications; whether granules, liquids, foggers or aerosols; and whether biological or organic pesticides. Records must be kept of all application sites, including crops, animals and buildings, indoors and out. Simply put, “If it has an EPA number and you use it in your business, KEEP A RECORD.”

These records can help with legal disputes; help prevent duplication of errors; help applicators note successes; and help plan pesticide purchases.

These records must be kept on file for two years and must be available for inspection upon request. Fish noted that private growers are not required to send reports of pesticide application to the Board of Pesticides Control.

Fish concluded his talk by noting that people may petition the BPC to define a Critical Pesticide Control Area around them. Medical or ecological proof of need for the Area must be provided.

Check BPC Web site, www.thinkfirstspraylast.org, for a list of pesticides registered for use in Maine, Worker Protection Standards, programs and regulations of the BPC, publications and more. Gary Fish can be contacted at 287-2731 or [email protected].