Leek Moth

Spinach/Beet Leafminers

Sunscald/Windwhip

Garden Springtails

Help Track Diseased Browntail Moth Caterpillars

The previous Pest Report discussed some issues created by cool and cloudy weather. With the much welcomed change towards warmer and sunnier days, take steps to avoid sunscald and/or windwhip on tender new transplants.

David Fuller of UMaine Cooperative Extension is reporting the first flight of adult leek moths in the northwest of Maine, earlier than he has seen previously. If you are near the areas where leek moth has been identified, take appropriate precautions for your allium crops. We are expecting this pest to continue its spread into Maine, so please familiarize yourself with it and its damage.

Growers in southern New England have reported some sightings of leafminer eggs on spinach and chard in high tunnels, but so far reports are far less numerous than several years ago when we had a couple bad years in a row. Garden springtails have also been spotted in high tunnels in Massachusetts, however, with the recent drying weather they are unlikely to become much of a presence this year.

Browntail moth caterpillars have emerged from their overwintering webs. You can help the Maine Forest Service track incidences of the caterpillars succumbing to a fungal disease which may help to control their population.

|

| Leek moth adults. Photo David Fuller |

|

| Leek moth caterpillar. Photo Scott Lewins |

|

| Windowpaning damage from leek moth. Photo David Fuller |

|

| Leek moth damage to onion bulb. Photo David Fuller |

| LEEK MOTH (Acrolepiopsis assectella) |

Leek moth is a newer invasive pest of allium crops like onions, garlic, shallots, chives, and as the name suggests – leeks. First introduced to Canada in 1993, it has been making its way south and east, and was reported in the northwest of Maine for the first time in 2017. Most growers in Maine will not see this pest this year, next year, and maybe not even for years to come, however, it’s important to know what to look for so that growers can help us to track the spread of this pest, and not be caught blindsided when it does arrive.

As with most moth pests the real damage is fromits larval caterpillar stage, of which there are two to three generations. Feeding damage can stunt growth as leaves are attacked, and later can impact storage and saleability of onions, garlic, and leeks as the second generation may eat its way in the direction of the bulb. If leek moth caterpillars are feeding on allium leaves around the time of harvest, the caterpillars will move into the bulbs as leaves dry down. Feeding damage and exit holes on bulbs while in storage can significantly reduce their marketability and open the bulbs up to secondary infection.

On flat-leaved garlic and leeks, the damage is often visible on the inside surface of the leaf, near the mid-rib, or in the garlic scape. In onions, damage can look similar to that of a leafminer because the caterpillar chews its way into the circular leaf, eating the interior layers of the leaf but leaving the waxy outer layer intact (called ‘windowpane’ damage).

Organic control options are limited, though a predatory wasp has been released in Canada, and will hopefully follow the pest across the border as well. The best practice for now is to use row cover to prevent adult moths from laying eggs on your crop. Row cover can be removed during the day to cultivate or harvest, as adult leek moths only fly at night. Spinosad (Entrust or MontereyGarden Spray) can be effective if applied 7 – 10 days following a peak flight.

Keep your eyes peeled for this new pest, and please let us know if you see it. Similar looking damage can occur from onion thrips, salt marsh caterpillar, or simply chlorotic leaf spots from several diseases (e.g., botrytis, purple blotch). There are a lot of helpful photos and more information at the leek moth information center website.

|

| Spinach leafminer eggs on left. Larvae at middle and mining damage right. |

SPINACH/BEET LEAFMINERS – Spinach leafminer (Pegomya hyoscyami) and beet leafminer (Pegomya betae)

These two species of leafminer attack spinach, beet, chard, and some weeds, such as lambsquarters. The spinach leafminer is more common. The adult is a fly that lays its eggs on the undersides of leaves. The eggs hatch in as few as three days, depending on temperature. The tiny, pale maggots tunnel into the interior of the leaf to feed, leaving pale mines that, when numerous, run together to form necrotic, blister-like areas. The damage is usually cosmetic, not impacting yield of beets, but it ruins the marketability of greens such as chard or spinach. When fully grown, the larvae drop out of the leaf to the ground and pupate in the soil. Leafminers overwinter in the soil as pupae and re-emerge as adult flies in the mid spring. Rotation is really important, especially if you are trying to use netting or row covers to exclude the fly, otherwise any overwintered pupae can emerge from the soil right where they want to be.

Controls include:

- Thorough harvesting where all leaves are removed, as well as, destroying crops at the end of harvest to reduce the egg and larval population. Similarly, controlling weeds, especially lambsquarters, chickweed, and plantain is important for reducing the number of overwintering pupae.

- Deep plowing can bury pupae and reduce the number of emerging flies the following spring.

- Row covers and netting if the ground is sure to not have overwintering pupae already.

- Because spinosad (e.g., Entrust, Monterey Garden Spray for gardeners) penetrates leaves to some extent, some farmers claim that it is effective against leafminers. It will be most effective if applied before eggs hatch and larvae enter the leaf.

|

| Notice the tan line where the squash leaf on the right shielded some of the leaf on the left from sunscald |

|

| Wind whip girdling a recently planted pepper seedling. Photo Rachel Stievater |

SUNSCALD/WIND-WHIP

Just like people unprepared for sunny days, plants that have not yet been hardened off thoroughly, or can’t get all the water they need, can suffer from something akin to a sunburn. The damage usually shows up first as a bleaching of exposed leaf surfaces, typically higher up on the plant, though sometimes only becomes apparent as necrotic leaf sections a day or two later. It can appear concerningly similar to a foliar disease.

Sunscald is caused by “photo-oxidative stress,” an over-loading of the plant’s photosynthesis system. We “harden off” transplants that have been started indoors, or inside greenhouses, because they have not yet devoted much energy to the coping mechanisms that will help them survive the drying winds and much stronger light they encounter outdoors. Adequate water supply is critical to plants’ ability to cope with these stresses. Plants that haven’t been hardened off, or are limited in water supply, are therefore more susceptible to sunscalding. Other root damage, such as damping-off or insect feeding damage may also impair sufficient water supply.

Seedlings that have been recently planted into black plastic mulch may suffer from tissue damage near the base of the stem. This is sometimes called wind-whip though it may be caused by a combination of bright sunlight, heat from direct contact with the black plastic and possibly some mechanical injury from strong winds – particularly if stems are a bit leggy.

The dead tissue caused by sunscalding can become an entry point for disease.

Best practices to avoid sunscald and other transplant issues, are to grow seedlings under bright light conditions and with plenty of air movement. Try to avoid leggy and pot-bound seedlings which may have inadequate root systems to supply the above ground growth. Harden off seedlings in a semi-protected area that provides “close to outdoor” conditions, with some shielding from wind and light extremes. Several days of hardening off are best, but even a single day will help as some of the plants internal stress response mechanisms are up-regulated quickly.

Actively growing plants are continually restructuring themselves, and you will notice that new leaves will be best adapted for the conditions they develop in.

|

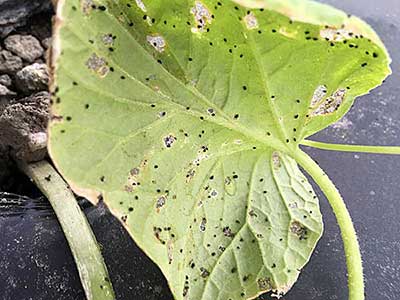

| Garden springtails on cucumber |

|

| A closer view of garden springtails |

GARDEN SPRINGTAILS

Springtails (Collembolla) are a very diverse group of soil dwelling arthropods, that largely feed on decaying organic matter. As such, most springtail species are playing a beneficial role in a healthy soil’s food web. That knowledge may be of little relief, however, if your young crop is one of the rare victims beset upon by large numbers of the garden springtail, Bourltiella hortensis.

At a glance, garden springtails and their damage resemble very much that of flea beetles, but springtails lack wings and are not true insects. They can be pale yellow to dark brown or gray. One defining feature of springtails is a tail-like appendage at the tip of their abdomen that they can use to launch themselves into the air, which is also the source of their name. Because they can’t actually fly, and because they favor tender young leaves, damage is typically restricted to cotyledons, and the first few true leaves low to the ground. Garden springtails are generalists and have been found feeding on squash, cucumber, beets, chard, beans, and even onions. However, the only reports of significant damage in New England that I’ve been made aware of are on young cucurbit transplants such as squash and cucumbers.

Though severe damage is very rare, large populations could set back young seedlings or even result in crop failure in extreme cases. Springtail lifecycles are short (less than 3 weeks from egg to sexual maturity), and females can lay up to 400 eggs in their lifetime, so populations could build up fairly quickly under favorable conditions. Conditions favorable to springtails are high in decaying organic matter and with protection from drying out, as they require fairly humid surroundings.

Management begins with common best practices; good sanitation to limit habitat, improved airflow to facilitate drying out between waterings, keeping greenhouse trays elevated on benches, and planting out vigorous seedlings that will grow past susceptible stages quickly. Spraying garlic on lower leaves has been suggested to deter garden springtails, though I cannot vouch for its efficacy. As a last resort, PyGanic is labeled for springtails.

|

| Browntail moth caterpillars infected by fungal disease. Photo Ellie Groden |

HELP TRACK DISEASED BROWNTAIL MOTH CATERPILLARS

The Maine Forest Service would like your help in reporting cases of diseased caterpillars in late May and June so we can track the progression of the outbreak. Infected caterpillars will have a puffy, swollen appearance and are covered in whitish/yellowish dust, which are spores of the fungi. As caterpillars succumb to the fungus, they will hold tight to the branches they die on which helps the spread of the browntail caterpillar-killing spores. Reports of diseased caterpillars can be made at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/9VKYFLV.

For more information on browntail moths, please see this website from the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.