|

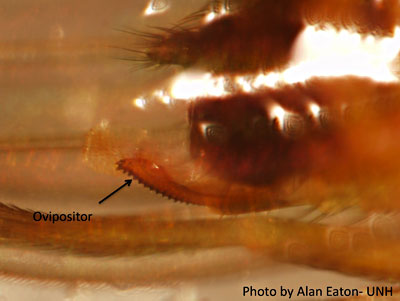

| Figure 1 – The female spotted wing Drosophila (fruit fly), a new pest in New England, uses her serrated ovipositor to make a hole in sound fruit and lay her eggs, which develop into larvae in the fruit. Photo courtesy of Alan Eaton of the University of N.H. |

By Eric Sideman, Ph.D.

I am usually not an alarmist. When local newspapers pick up stories about crops ruined by weather or pests, my initial reaction is usually, “Here they go again, sensationalizing stories to sell newspapers.”

Once in a while, though, I am as nervous as the media, and this is one of those times. The spotted wing drosophila (SWD) is just the kind of threat that all of us who grow soft fruit need to notice.

A casual observer would not notice this new pest. It looks much like the common fruit flies we see on over-ripe fruit on the kitchen counter or in the field and garden. Almost everyone thinks, “Yuck,” discards that fruit, and the game is over for the fruit fly.

The SWD, however, not only goes after over-ripe fruit but can also lay eggs in sound fruit. The female uses a structure called an ovipositor to make a hole in the fruit and lay eggs, and in this species of fruit fly, the ovipositor is serrated (Fig. 1) and can puncture the fruit. This pest, new to our area, shut down the fall raspberry harvest in Connecticut last year. Maggots that develop in the fruit from SWD eggs are not good for business.

The SWD, a common pest in Asia, is sometimes called the Asian fruit fly here. It was first seen in Hawaii in the 1980s and in California in 2008. In 2010 it jumped to Michigan and South Carolina. Last fall it appeared in New England – in August in Connecticut and by September in Maine.

We may think that this pest could not survive our winters, but it can. It does fine in similar climates in Asia. It may need to hide under a log or in a structure, but don’t count on the winter killing it.

|

| Figure 2 – Male spotted wing Drosophila have a spot on each wing. Photo courtesy of Alan Eaton of the University of N.H. |

This little fly looks like the common fruit fly we often see in our kitchens, but with a spot on each wing of the males (Fig. 2), visible with good eyes or a simple magnifying glass. Remember, only males – half the population – have spots.

The SWD is a pest of soft fruits, such as strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries, cherries, grapes, plums and peaches. I also saw it last year on tomatoes in our high tunnel in New Hampshire, but only on cracked fruit. Of course, tomatoes are a pretty soft fruit, so I’d anticipate seeing them on the list of sound fruit attacked. Apples seem to be at low risk, and the SWD has not been seen on cranberries yet.

This pest overwinters as an adult, which is uncommon for a fly that can tolerate the cold. It hides under litter or in buildings and emerges when days are regularly in the 50s, or at about 268 degree days.

The adult does not have to overwinter in the fruit field. It can overwinter in the woods or forest edges and find the field later by the fruit smell.

The overwintering population is probably small, but the generation and doubling time is very short, so populations can explode quickly. Each female lays about 300 eggs, one to three per sting, which hatch in two days. Maggots feed on the fruit for about 10 days and then pupate. New adult flies emerge from pupae in about four days. So in less than three weeks, the population of fruit flies can go from 2 to 300; in six weeks, to hundreds of thousands; in nine weeks, to millions; and in 12 weeks, to trillions!

Of course, in nature not everyone survives, but this math exercise illustrates how much more of a problem this pest will be later in the season than earlier. I think that June-bearing strawberries may escape a major attack, but raspberries, blueberries, fall strawberries, etc., may get hit hard.

This new pest may destroy Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs, whether organic or conventional. The basis for IPM is the integration of all pest management strategies, including crop rotation, sanitation, natural controls, and spraying only when monitoring demonstrates need. But SWD populations can explode quickly, and consumers tolerate maggots in the fruit much less than, say, an earworm in corn. I would say tolerance of maggots is about zero.

At this time, I know of nothing other than frequent spraying of pesticides that will get populations to zero, or near zero, but I hope lots of new management options arise.

Monitoring is still important to minimize pesticide use. New England Extension personnel will be setting up traps to see how bad this pest is this year.

Many pesticides work well, including Entrust, which is allowed in organic production – but spraying every three to five days will probably be necessary for good control. We hope to avoid that for many reasons, including environmental impact, cost, image and resistance build up. If growers need to resort to spraying, let’s not do that until monitoring shows a need. Even though Extension is doing a good job, I suggest you monitor on your own. This fruit fly, like all others, is attracted to apple cider vinegar, but the best bait found so far is a mix of yeast and sugar (see sidebar).

I am part of a group of concerned Northeastern educators meeting in March to pool thoughts and to learn. I will keep you all posted.

Thanks to Alan Eaton at the University of New Hampshire and Frank Drummond at the University of Maine for much of this information.

Eric Sideman is MOFGA’s organic crops specialist. You can address your questions to him at 568-4142 or [email protected].

Make Your Own Traps

Supplies

1 Tbsp. live baker’s yeast

4 Tbsp. sugar

12 oz. water

4- to 5-quart transparent deli containers with lids

Small yellow sticky cards (available from Great Lakes IPM, etc.; optional)

Wire to hang traps 3 to 5 feet from the ground

Mixing the bait

Stir together live yeast, sugar and water in a container large enough to handle a bit of expansion. Let the mixture ferment for 24 hours.

Building the trap

Drill seven evenly spaced 3/16-inch holes near the top of the deli containers, leaving 1/8 of the rim diameter without a hole so that you can pour used bait out of that side without having it spill though a hole.

Insert wire through two holes on opposite sides.

To be able to count SWDs, drill a hole in the container lid and hang a sticky yellow card inside the container, above the level of the bait.

Add about an inch of fermented bait to the container, snap on the lid, and hang the trap 3 to 5 feet from the ground. Replace the bait every week or two.

For an image of the trap and more details on making it, see www.ipm.msu.edu/invasive_species/spotted_wing_drosophila/monitoring.