|

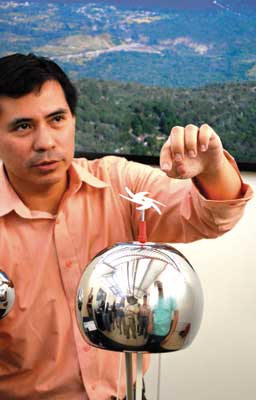

| Bernardo Bellosa (far left) and Pedro Cabezas (next to Bellosa) from the Association for the Development of El Salvador gave members of the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering delegation an overview of environmental issues facing El Salvador. We told members of our sistering organizations about organic farming successes and challenges in Maine – and shared posters for the Common Ground Country Fair. English photo |

|

| Conventional sugar cane cultivation uses large amounts of synthetic pesticides, including glyphosate (for weed control and to desiccate the crop near harvest time), synthetic fertilizers and water – a scarce resource in El Salvador. English photo |

|

| A forest was being cleared behind us to make room for more sugar cane cultivation as we heard from citizens about the harm that crop was doing to their health and environment. English photo |

|

| Mechanical harvesting is coming to sugar cane – a mixed blessing, as it will eliminate jobs, but working in sugar cane seems to be related to chronic kidney disease. English photo |

|

| A group of women in Guarjila grows and promotes use of more green vegetables in diets. English photo |

|

| Cooking with native plants. English photo |

|

| Adding chopped green vegetables to pupusa dough. English photo |

|

| Delegate Karen Volckhausen with the Virgin of the Resistance. Citizens of San Jose Las Flores placed the statue there after telling a Canadian gold mining company that they did not want their land and water destroyed by that industry. Paul Volckhausen photo |

By the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee

For 16 years MOFGA has had sistering relationships with two MOFGA-like organizations in El Salvador: CCR (Coordinating Committees for the Development of Chalatenango) and CORDES (Foundation for Cooperation and Communal Development of El Salvador). In late January/early February 2017, five members of the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee spent 10 days visiting 10 Salvadoran communities and three community radio stations where CCR and CORDES work. We deepened our understanding of organic farming and gardening in El Salvador and of social, political, economic and environmental gains and struggles. Whether talking about El Salvador’s civil war, seed saving, immigration, resisting Monsanto, or other topics (lots of talk about Trump!), we were frequently reminded of the importance of international solidarity.

Weather, Climate Change and Other Environmental Stressors

Pedro Cabezas from CRIPDES (the Association for the Development of El Salvador; the largest rural organization in the country, a leader in the Salvadoran social movement and coordinator of sistering relationships there) said that water stress and deforestation have led to soil erosion and to soil and water contamination, and climate change has led to drought and floods – and, said Bernardo Bellosa, also from CRIPDES, to increased prices.

In the farming community of Buena Vista, which produces sugar cane, honey, fish and cows, we learned that the Juan Chacon Cooperative has had trouble exporting its apiculture products because climate change has favored an insect that feeds on sorghum. Plants can be treated with liquid soap, but that’s expensive. Products have to be lab-tested to know that they’re safe to consume before being exported. Also related to climate, the cooperative plans to begin irrigating its pastures.

Food, Water and Seed Issues

In a few years, El Salvador won’t be able to provide equal access to water for all of its population, said Cabezas. Water stress is caused mainly by deforestation, which leads to erosion (which affects 75 percent of the country and has caused extensive loss of topsoil), which leads to contamination. Agricultural and industrial chemicals are also contaminating waters. More and more ag chemicals are being used to produce the same amount of food because of soil degradation. Some agricultural chemicals may also be associated with chronic kidney disease.

At the same time, rivers are drying up and are now being called “winter rivers.”

At this point, 98 percent of the surface water in El Salvador is unfit for human consumption. We were told that many studies conclude that El Salvador is the country with the least water available per capita in the region, and the country will be in a water-related crisis in 15 to 20 years. Signs of the crisis already exist, but the country has no plan to deal with it.

In Carasque, for example, the current water source for 338 people in the community is drying up – due to climate change, we were told – so the community is working on a plan to get water from the nearby river. That water, however, has a pH of 3.4 and contains excess nickel, iron and manganese that will need to be removed. The project is expected to provide good water to seven communities and will cost about $60,000, which will come from the community, from CCR and from nongovernmental organizations.

Despite these water issues, a new, 7,400-acre Class A golf course is been developed in El Salvador, along with a big hotel and convention center. The untaxed enterprise is in an area of farming communities, and those farmers are losing access to water as the golf course is irrigated.

The Salvadoran government also lets a plant bottle water, beer, Coca Cola and other drinks even amid the water crisis, said Cabezas.

Plan Panama stipulated that at least 12 hydroelectric plants be created in El Salvador. The two already developed are creating social problems in nearby communities in El Salvador and Honduras.

Movements exist to promote access to water and food as human rights, but the Legislative Assembly is split between the four right-wing parties and the left-wing FMLN party. In 2012, the Legislative Assembly did recognize the right to food and water in the Salvadoran constitution, but that action was never ratified. The two sides are at a stalemate regarding a law ensuring equal access to water for everybody and keeping water in public, not private, hands.

The push for food sovereignty legislation seeks to strengthen local food production by supporting small and medium-scale sustainable agriculture, recovering native seeds and providing equal access to land, water and seed. This includes ownership of land, especially for women. Of the 104 articles in the proposal for food sovereignty, the Legislative Assembly has discussed 32 so far. The right wing disapproves of articles that may regulate agricultural chemicals or junk food in schools, said Ernesto Morales, director of CORDES in Chalatenango.

The Salvadoran government, said Cabezas, is trying to retain traditional crops and to buy a quota of organic seed from Salvadoran farmers to redistribute, but, due to Monsanto’s influence (via its Central American representative, Semillas Cristiani Burkard), settled for a much smaller percentage of organic seed than originally wanted.

Bellosa addressed the excess influence of a U.S. ambassador encouraging El Salvador to sign an agreement of public/private association in order to get funds from the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a U.S. aid agency. The agreement allows big companies to exploit El Salvador’s natural resources. “They are going to try to privatize every natural resource we have,” said Bellosa.

Yet another agreement, the Partnership for Growth, he added, was created by the Millennium Challenge Corporation and supported by President Obama and Vice President Biden. It enables the United States to influence economic and security policy, including the judiciary, in Ghana, El Salvador, the Philippines and Tanzania.

Bellosa noted that a law to prohibit the use of 53 agrochemicals was introduced to the Legislative Assembly but didn’t pass – due in part to the influence of a U.S. ambassador and Monsanto, he added.

Likewise, bills were presented to the Legislative Assembly in 2007 to prohibit metallic mining, in 2009 for the human right to water, in 2010 for food security and sovereignty, and to promote organic agriculture. None passed. (Update: On March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran Congress voted overwhelmingly to prohibit all metallic mining nationwide – the first country to do so.)

The government, said Bellosa, could encourage organic curricula in schools; promote local organic kitchen gardens; and eliminate laws and agreements that have hurt the environment, such as CAFTA, the Central America Free Trade Agreement, which led to social, political and economic problems. A government program is supporting some demonstration farms using native seeds and is increasing the production of native seeds to distribute to farmers.

Sugar Cane

We learned more about the devastating effects of conventional, monoculture sugar cane production and processing by the country’s six major sugar refineries (Jiboa, El Angel, El Chaparras, Tique, La Cabaña and Centro de Izalco). Intensive use of pesticides, including glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup, used pre-plant and at the end of the crop cycle to “ripen” plants and concentrate sugars), paraquat and gramaxone, applied with backpack sprayers and aerially, is contaminating soils, water, crops, home gardens and people and killing livestock.

Water being diverted from rivers and lagoons to irrigate cane plantations dangerously limits the people’s access to water. Local farmers use 2-inch pipes for irrigation, while sugar cane plantations use 9-inch pipe, irrigate day and night, and use water for processing as well. In Los Anonas we were told, “When we dig a well now, we cannot find water.” That community now brings in all of its food and water to meet its daily needs.

In addition to agrochemicals, burning is a problem (burning occurs before harvest so that only canes and not leaves are harvested and transported to mills), and cane production is destroying mango groves and increasing deforestation generally. In fact while we met with the community board of Las Anonas, surrounded by sugar cane plantations, we struggled to hear one another as men with chainsaws cut the last tree in a former forest adjacent to our meeting area in order to make more room for sugar cane planting.

Cane stalks are transported daily to refineries in trucks much like the logging trucks that we see in Maine, and the trucks kick up dust and damage roads.

Representatives of CRIPDES and MOPAO (the Popular Movement of Organic Agriculture) in San Vicente told us that they are encouraging municipalities to pass ordinances to regulate synthetic chemical use on sugar cane plantations – and to have existing ordinances enforced. CRIPDES participated in a roundtable at the Office for the Defense of Human Rights in El Salvador, which investigated the impacts of chemicals used on sugar cane. They disseminated the results to the communities. Unfortunately, said Esmeralda Villalta, general coordinator for CRIPDES San Vicente, plantation owners don’t respect the rights of people living near their plantations to be protected from aerial spraying. Also, smoke from burning crop residues has killed nearby animals.

Marixa Amaya, who coordinates youth programs for CRIPDES San Vicente, explained that the communities are very well organized and have tried to encourage plantation owners to obey ordinances. They even held action days when they blocked roads so that owners and workers could not get to the plantations, but some local family members work on the plantations and feared losing their jobs. In Los Anonas we also heard about cane workers being exploited. When the Salvadoran government required a raise from $5 to $6 per day, plantation owners added more work to each worker’s daily load.

This exploitation and contamination of workers may end soon, but not due to companies’ largesse. Instead, machine harvesting is coming, so these agricultural jobs may be lost.

Sixty percent of Salvadoran sugar cane is exported to the United States, according to Abel Lora (president of the agricultural group CONFRAS el Salvador, Confederación de Federaciones de la Reforma Agraria Salvadoreña, which represents more than 100 cooperatives). We were told that buying organic sugar would help somewhat but that the demand is low. We were urged to support any calls to action by these communities for the government (especially the Ministries of Agriculture and of the Environment) to enforce existing ordinances. Unfortunately owners of two of the six major sugar cane companies are in the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly and block any such actions. The possibility of boycotting Salvadoran sugar was mentioned, although others pointed out that this would put jobs at risk. MOPAO has been educating people about producing cane without using synthetic chemicals.

Despite all the issues with conventional sugar cane production, the people of Los Anonas are planting cacao and cashews on their community land and are inspiring others to plant trees around their homes.

Mining

Some 15 mining companies have undertaken dozens of exploration projects in El Salvador, a country the size of Massachusetts. Mining uses cyanide, considerable water, involves deforestation, and leaves behind material that generates acid drainage. Many Salvadorans want a federal law to prohibit metallic mining, but the main line of resistance now seems to be at the community level.

Five municipalities in Chalatenango have passed ordinances prohibiting mining companies from entering. And on March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran Congress voted to ban metallic mining nationwide. Rubia Guardado from the CCR board in Chalatenango said that an anti-mining demonstration occurred every two months in front of the World Bank building.

In San Jose Las Flores – the first community to ban mining – we heard about a Canadian mining company that in 2004-2005 flagged areas there. The community organized and asked them to leave, but the company was unwilling to negotiate. So the community placed bee hives in the marked area. The people also pulled the survey flags and mailed them back to the Canadian company. The company left for a while but later returned – and the people of San Jose Las Flores wouldn’t let them pass. The people also carried a statue of the Virgin Mary – the “Virgin of the Resistance” – to the mountain to show respect for and protect the land. (Some of us hiked to the Virgin – an endeavor we don’t recommend except for those in top shape.) Every September 14 since then they have celebrated the Virgin of the Resistance. The community also watched videos of the effects of mining in Guatemala and Honduras. CRIPDES, CCR and CORDES organized anti-mining marches in San Salvador, and a round table against mining was organized.

The current government has worked hard to keep the mining companies out of El Salvador and even won a lawsuit brought by the company Oceana Gold when that company alleged it had lost profits because it wasn’t allowed to mine. Salvadorans are still waiting for Oceana Gold to pay the $8 million in legal fees ordered by the International Court for the Settlement of Investment Disputes when it dismissed the company’s lawsuit.

|

| The certified organic cashew nut producer cooperative Aprainores is a success story in El Salvador, employing more than 100 people. English photo |

|

| A cashew fruit (used to make wine and dried fruit) with the cashew nut protruding at the base. English photo |

|

| Students at the Amún Shéa school in Perquin make compost … |

|

| grow vegetables … |

|

| raise fish … |

|

| and learn using hands-on methods. English photos |

|

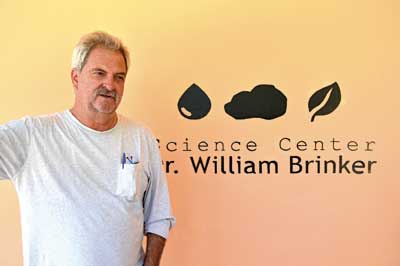

| Ron Brenneman built and started the Amún Shéa school, the science learning center and, most recently, a soil/plant/water testing lab. English photo |

Organic Farming Successes

We met with MPR 12, the Popular Resistance Movement of October 12th, which is the national day of resistance of the pueblo. Thirteen organizations make up MPR 12, which supports private businesses, cooperatives and communities.

Accompanying MPR 12 was Abel Lora of CONFRAS, who said that of the 11,000 Salvadoran producers in CONFRAS, all members of cooperatives, 17 percent are considered organic. Some are in the process of certifying. CONFRAS is active in promoting fruit tree planting, encouraging women farmers to take leadership roles in the organization, and pushing for enactment of a food sovereignty law. Through the Center for Research and Transfer of Agro-Ecological Technology (CIETTA), it shows organic production methods, including vermiculture and making bokashi, and saves and uses its own corn and bean seeds. Cooperation with Sister Cities, said Lora, has enabled them to protest Monsanto and its efforts to supplant native Salvadoran seed with its patented, genetically engineered seed.

Lora added that eight countries have organized to form the World Rural Forum (https://www.ruralforum.net/en), which, among other things, petitioned the United Nations to declare 2014 the Year of Family Farming.

In San Vicente, Fermín Meléndez, the director of MOPAO, told us that MOPAO is working in seven communities to raise awareness of issues related to agricultural chemicals and about ways to protect native seeds. Because of limited finances, most organic farmers in the area use IFOAM’s Participatory Guarantee System for farmer-to-farmer certification. The demand for their organic products exceeds the supply.

Meléndez also said that El Salvador’s national agricultural school hopes to institute a curriculum in alternative agriculture, and a certification organization supports this.

In San Vicente we visited an organic cashew nut producer cooperative called Aprainores. We learned that the nuts are dried on a patio outside the facility, then brought indoors to be roasted in an autoclave at 250 C. Reject cashews are used to fuel the autoclave. Then the nuts are cut in half by 30 workers who wear masks, gloves and protective clothing to guard against the toxic oil in the shell of the nut. The shells are removed by hand and the nuts are further sorted. Any rejects at this point go into animal feed concentrate. Ten women then grade the nuts, which are packed and exported to Europe and the United States – sold for $7 per pound, wholesale. The buyers (including Equal Exchange) sell bagged nuts or process them into cashew butter.

The coop employs 80 to 90 people – 70 to 80 percent of whom are women – and another 150 work in the cashew plantations. In a good year Aprainores produces 5,000 quintals (about 500,000 lbs.) of cashews; last year only about 2,000 quintals were produced because of drought. Trees with big fruits produce about 3 quintals of seeds each. Grafted trees produce in about three years; non-grafted take five. Trees are fertilized with bokashi (fermented compost). Pests include an ant, which takes water from trees; a fungus that affects flowers and roots; and cockroaches. Growers counter these pests with the organic product M5, made by fermenting chili peppers, garlic, mint, ginger and onions in alcohol. The cashew fruit is used to make wine or is dried and mixed with dried mangoes, pineapple, plantain and papaya. Plots growing cashew trees for Aprainores are collectively certified.

Reforestation

We visited a hillside in Guarjila that was being reforested with mango and cashew trees, a bamboo reforestation project and a well run community composting operation.

In Chalatenango we learned about CORDES’ work to reforest 6 acres of land along rivers in order to preserve soils. This and other reforestation plans in the area strive to promote plant and animal biodiversity, partly to promote tourism. Ernesto Morales, director of CORDES in Chalate, said the reforestation there includes a walking tour so that people can buy products that come from the forest.

In San Jose Las Flores we saw an asper bamboo propagation nursery. Once plants are large enough, they are planted throughout the community to hold soil and filter water that is high in sulfur, manganese and various contaminants.

The community of Arcatao has set aside about 4 acres of land for a nursery for trees that can be used later for construction and reforestation. Each family will take care of one tree, which will be assigned the name of a martyr from the area so that the project has a historical meaning as well. In addition each family got 10 fruit trees, including orange, anona, guava, mandarin, avocado and others, to plant around their homes. Arcatao is reforesting the area where most of its water comes from. The community hopes to buy that land so that mining companies won’t have access to it. It is seeking technical advise on which trees would be appropriate for reforestation in its mountains.

School and Home Gardens

Some of the communities we visited were promoting organic kitchen gardens and consumption of more green vegetables in the diet. We also toured two amazing schools that produce food. The first was in San Jose Las Flores, where the entire school grounds were a botanical garden, with labeled plants, dozens of kinds of butterflies, vegetable gardens and a fish pond. Students even grew the food for the fish. The gardens and food production were completely integrated into the school curricula.

The second was in Perquin, in the eastern part of El Salvador. We had heard about this school and its founder, Ron Brenneman, from a woman named Stephanie Mollica, who visited our committee’s table at the Common Ground Country Fair. All of us read Brenneman’s book “Perquin Musings” to learn about his move from Delaware to the El Salvador/Honduras area as an aid worker, his numerous experiences during the war and his decision to stay in El Salvador afterward. In 1999 he used his construction skills to build his ecological Hotel de Montaña Perkin Lenca, where we stayed – and delighted in the solar-heated shower water.

In 2008 Brenneman started building Amún Shéa, a private, nonprofit school for students (including his children) who commute from six municipalities. Now about 80 students in the multi-age classes “learn and apply, learn and apply,” said Brenneman. The school could easily handle 100 students, he said. The 14 staff members mentor rather than teach the students. “We want a dynamic class without the direct intervention of a teacher,” he said.

We watched as students made compost from coffee pulp, chicken litter, microorganisms, wood ash, leaves and other ingredients.

Although private, the school has public alliances – as with the Salvadoran government and the national university associated with a new water/plant/soil testing lab on campus.

One greenhouse (a net house to exclude insects) at the school produces food for the school cafeteria and occasionally for local restaurants when crops are overproduced. Another, new house will produce crops to create value-added products, such as tomato sauce, as well as tilapia. The idea is to consume 50 percent of the food from these two greenhouses and from an outside garden and fish ponds, and to sell 50 percent in order to become self-sustainable.

Another new building on the campus is the third interactive science learning center in El Salvador, and the only one in a rural area. Brenneman envisions students learning through hands-on lessons in the four rooms of the center – one each for physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry – and then applying those lessons to real-world needs, and gaining patents for their work along the way. Lessons learned at the interactive center will be linked to the school grounds, by, for example, developing an interpretive path and botanical garden, with the flora identified.

Brenneman also has plans for the 22-acre site to build a community center, to develop a rain catchment system from all roofs so that all water is used at least twice, to add rooms for robotics and for music and math to the interactive learning center, and to raise money for more scholarships. He is creating a contest in which students identify a problem, and the school will finance a solution that the winner develops.

The first class will graduate from Amún Shéa this year. Brenneman says the goal is for them to have the right attitude and abilities to do social and economic work in the area. The two local high schools turn out more than 200 accountants each year, and Brenneman questions the need for so many accountants in this rural area. He would rather identify the needs of the community (e.g., a certain number of lab techs, eight to 12 alternative energy techs, people who speak English and can work in the tourism industry) and guide students toward those careers.

Brenneman’s nine-year plan is “to leave the same way I came – with a backpack,” and to have the school running on its own.

Work with Women and Youth

Juanita Morales from CCR in Chalatenango told us about CCR and CORDES’ work with about 6,000 women – on organizing microcredit, empowerment, providing technical training, including women in political decisions, promoting land ownership by women, promoting kitchen gardens and “green food,” working against violence toward women and recognizing the hard work women do at home.

Similarly, CCR in Chalatenango empowers youth in dozens of communities. The youth talk about local social issues and create social and cultural plans for their communities. The learn skills that can create environments free of violence, and they learn entrepreneurship skills, including marketing. Last year CCR in Chalatenango supported 32 enterprises in agriculture, aquaculture, planting fruit trees, raising chickens, hairdressing and construction.

Community Radio

At Radio Sumpul (WERU’s sister station), we learned that the station was founded in 1993 in San Jose Las Flores. In 1994 the right wing ordered the police to capture the people and equipment from the station. The community, in response, closed the roads so that the police couldn’t leave. The community then negotiated for the police to commit that if the equipment suffered, they would have it repaired.

When the station resumed broadcasting, it suffered other setbacks, including having the building burned by accident, and having its transformer struck by lightning, twice.

Radio Sumpul has reorganized its staff since our last visit. It is now broadcasting from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. rather than 24 hours per day, and it is one of 22 community radio stations with the same frequency, organized under ARPAS (Radio and Participative Programmes Association). We visited two other community radio stations connected with ARPAS.

Lasting Effects of the War

Tours of museums and talks with community residents reinforced the horrors of the war, the amazing powers of forgiveness among Salvadorans (as well as residual trauma), and the tremendous extent to which communities have been rebuilt in just 30-some years.

In Guarjila, a young community board told us that they were all very young when they returned from a refugee camp in Mesa Grande in Honduras, where they had lived for nine years. One spoke of the trauma she suffered when, at age 15, she watched as the Salvadoran army killed her parents in front of her. About 15,000 to 20,000 refugees lived in Honduras, with limited water, services or space. Anyone who left the refugee camp would be captured and disappeared. The refugees were thankful for the international organizations that accompanied them while they were in Honduras.

They returned on October 11-12, 1987, crowded in and on top of buses, which the border patrol held up for one night. When they finally got to Guarjila, there were no more trees – just shrubby growth – and bullets continued to fly through the community until the peace accords were signed in 1992. They returned to the seven or eight remaining houses, with 15 to 20 families living in each house with no potable water and with the threat of nearby land mines.

With support from international solidarity organizations and from CCR, they built new houses, got electricity for two places where they could gather to talk, and eventually had a school, church, electricity and water. Community members would work four days per week for their families and three days on community projects.

In Arcatao we toured a museum and a church dedicated to remembering the war and the martyrs. We were struck by our guide’s perception of a fairly new army base just outside of town. Despite having been captured and tortured by the army during the war, she said that the soldiers at the new base are not those who tortured her, and she held no animosity toward them.

Immigration

Almost every community expressed concern with the U.S. crackdown on immigrants – about people who committed crimes being sent back to El Salvador, as well as people who are hard workers in the United States and who support their families in El Salvador. At least 2 million Salvadorans now live in the United States and just over 6 million live in El Salvador. The “remittances” sent by many of those 2 million to their families each year make up a large part of the Salvadoran economy.

Some family members have permission to work in the United States for a limited time only, and they don’t know how Trump’s immigration restrictions will affect them. Also, families worry about how Trump’s speech promoting discrimination against Latin Americans affects their family members in the United States.

“All that is left is for us to try to be united and look for solidarity support,” said CCR board member Jose Milton Monge Alareza.

Crime

We heard less about gang violence in El Salvador during this trip and sensed a more relaxed population in that regard, despite (or because of) the common presence of police, military and private security personnel armed with assault rifles. We were told that the government had taken away knives, cell phones and cell phone signals in prisons (from which gang murders had often been ordered); had put more army and police personnel on the streets; and many communities had organized to prevent violence. As a result, homicides have decreased from more than 30 per day in mid-2016 to 10 per day.

The government also began a national system of community police, who come to communities to monitor the crime situation. Anyone in the community can inform these police about issues. We were told in Carasque, however, that some police personnel were connected with gangs, so when the police came there, the community board let them know that they – the police – were being watched, as well.

Summary

We were struck by how far all of the communities we visited had progressed since the war. This development continues, with communities striving to find land and help build homes for those who grew up locally and now have their own families, and to install more latrines and water filters.

We also heard repeatedly about the importance of international solidarity, whether through direct aid (e.g., Philadelphia helping its sister community of Los Anonas with moral and economic support to build a church, community kitchen, storeroom and meeting room and five new houses, repairing 30 existing houses and putting in 25 latrines in this 91-family community). “Solidarity,” said Ernesto from Los Anonas, “is present in the good and the bad moments.”