|

|

|

Rotations with winter and spring cereal grains have good possibilities in Maine, said Dr. Matt Liebman at a MOFGA-sponsored talk at the Maine Agricultural Trades Show in January. The keys to successful cereal production, he continued, are adequate weed control – especially paying attention to mechanical weed control – and adequate soil fertility.

Regarding winter cereals in Maine, winter wheat and rye are generally seeded in September, when the soil is drier and soil compaction is less likely than with spring cereals. These winter cereals will be harvested in late July or August of the following year, allowing cover crops to be seeded afterward. Liebman pointed out that winter cereals require good drainage and snow cover to survive. Advantages of growing them are: they yield more than spring wheat; they compete very well against spring-germinating weeds; and they conserve soil in winter and spring.

Spring cereals – spring wheat, barley and oats – are generally planted as early as the ground can be worked into a good seedbed. These early plantings provide important yield and weed control advantages; if plantings are delayed, higher seeding rates should be used. Spring cereals are harvested from late July through September. They can survive in areas where winter cereals cannot. If both crops can be grown, however, yield of spring wheat is generally less than that of winter wheat, said Liebman.

Liebman listed three possible rotations using these crops:

Year 1 winter wheat, oil radish

Year 2 oat and pea underseeded with red clover

Year 3 soybean, winter rye

Year 4 rye, buckwheat

Year 5 barley underseeded with red clover

Year 6 red clover, winter wheat

Year 1 pea, oil radish

Year 2 spring cereal underseeded with red clover

Year 3 red clover, winter cereal

Year 4 winter cereal, buckwheat

Year 1 winter wheat, oil radish

Year 2 oat underseeded with red clover

Year 3 barley, winter rye

Year 4 winter rye, oil radish

Year 5 barley underseeded with alfalfa, timothy and brome

Year 6 forage

Year 7 forage

Year 8 forage

Year 9 forage plowed, winter wheat

Source: Macey, 1992.

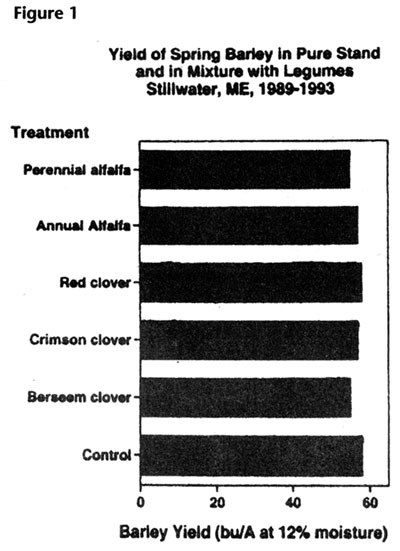

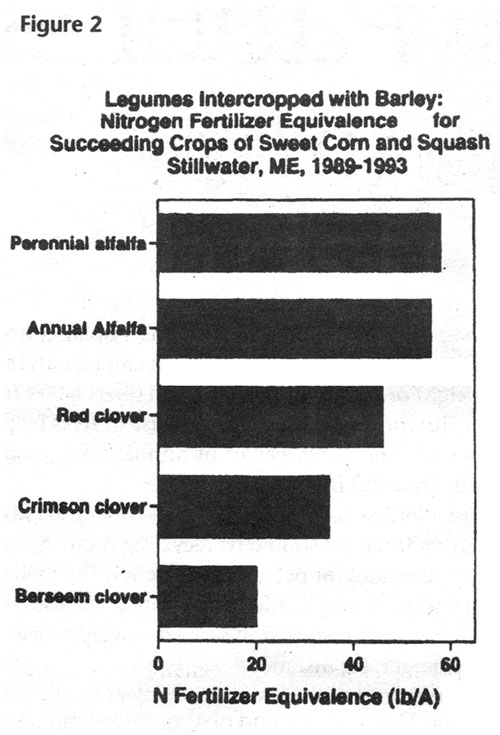

Liebman reviewed data from work that he and his coworkers at the University of Maine had done, as well as work from other areas to make several points about these crops. For example, when sweet corn and squash were grown in two-year rotations with barley underseeded with various legumes, after the barley grain was combined off (in July or August in south or central Maine), the field was left with a “decent cover” of the legume in the fall. Barley yields were not affected by addition of the legume (Figure 1), and nitrogen gained for the corn and squash crops ranged from about 20 to 60 pounds per acre (Figure 2). “The amount of nitrogen recovered depends on the amount of root growth in the first year more than regrowth in the second year,” he said. Most successful for weed control were mammoth red clover and crimson clover, while alfalfa grown under barley was less competitive against weeds.

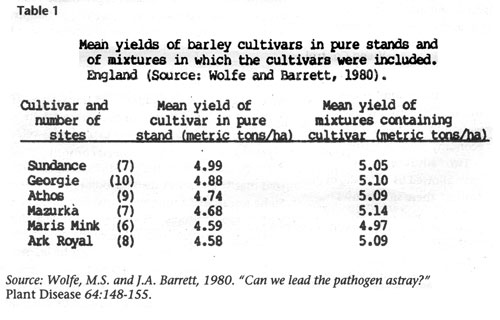

Mixtures of barley cultivars might produce higher yields than single cultivars, Liebman continued, because different cultivars will have different tolerances to various strains of disease. “A mixture of varieties is harder for any particular strain of disease to hit,” he said, “so there will be less buildup of disease than in solid stands of a single variety.” This should lead to higher yields. He cited data from England (Table 1) showing higher yields in stands containing mixtures of cultivars versus pure cultivars.

|

|

|

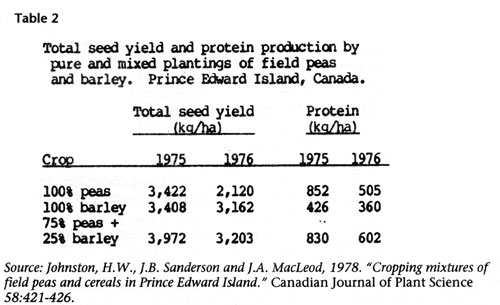

Another advantage of intercropping legumes with cereals is given by field peas mixed with cereals, such as barley. The cereal raises peas off the ground so that less disease occurs and a greater total yield of protein and seed may be achieved (Table 2). Peas make an excellent green manure, Liebman said, but seed costs are high.

Oats offer a low-cost cover crop and the seed is readily available. They provide a good way to hold the soil cheaply; they can be planted for grain in the spring with red clover or into the fall as a cover crop.

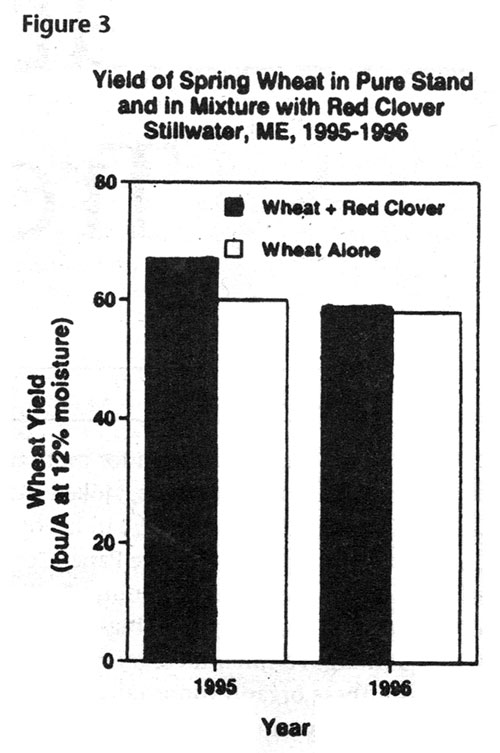

Spring wheat “grows quite well in Maine,” said Liebman. It can be sown with red clover, harvested with a combine, leaving a stubble. “We’ve seen no yield penalty when it’s intercropped,” he explained (Figure 3). The clover foliage adds 60 to 100 pounds of nitrogen per acre when it’s incorporated into the soil in May, and more is available from the roots.

Regarding winter rye, Liebman said that this vigorous cover crop grows up to 6 feet tall in central Maine by the end of May, adding a lot of organic matter to the soil. Its disadvantage is that it sequesters nitrogen in the straw, and the straw takes a while to break down – but that slow breakdown keeps organic matter levels higher longer than if the straw broke down quickly.

Winter wheat, he said, fits well when rotated with summer crops, such as dry beans. “You get good weed control when you alternate summer crops with winter crops.“ Crops such as winter wheat and barley can help with insect control, too, said Liebman. Barley, spring wheat or oats can be rotated with potatoes, and a trench lined with plastic between the crops can prevent migrating Colorado potato beetles from moving from one field to another. Table 3 shows the great reduction in Colorado potato beetle egg masses and larvae per plant when potatoes followed wheat instead of following another crop of potatoes.

Intercropping cereals and legumes can help with weed control, too. Table 4 shows that barley undersown with red clover controlled quackgrass better than barley alone. Similar results have been achieved with barley and alfalfa, and the legume has added about 60 pounds of nitrogen for subsequent crops at the same time. Again, noted Liebman, while alfalfa adds more nitrogen for the subsequent crop, clover gives better weed control.

– Jean English

| The five cereals that Liebman discussed have the following characteristics: | |||||||

| Crop & Target Yield, bu./A | Lbs./A Removed if Crop Reaches Target Yield Level | Test Wt. lb./bu. |

Seeding Rate lb./A |

Can Sow With | Weed Control | ||

| N | P | K | |||||

| Barley, 80 bu/A | 70 | 30 | 20 | 48 | 100-130 | Forage legumes and grasses, or peas. | No missing rows or skips in seeding; Spring-tine harrow pre-emergence & at 3- to 5-leaf stage; (Incorporate forage grasses & legumes w/last weed control). |

| Oats, 80 bu/A | 50 | 24 | 18 | 32 | 90-130 | “ | Same as barley |

| Spring wheat, 70 bu/A | 90 | 35 | 20 | 60 | 120-150 | “ | Same as barley |

| Winter wheat, 80 bu/A | 105 | 40 | 25 | 60 | 120-150 | Easily frost-seeded w/forage legumes. | Good control of perennials via tillage before planting; No missing rows or skips in seeding. |

| Winter rye, 30 bu/A | 35 | 15 | 10 | 56 | 100-150 | Can be frost-seeded w/forage legumes in spring. | Same as winter wheat. |

| Source: Macey, A., editor. 1992. Organic Field Crop Handbook. Canadian Organic Growers, Inc., Ottawa, Ontario | |||||||