By Lauren Cormier

Even with the best intentions of buying local and avoiding produce from many miles away, it can be difficult to resist the temptation of apricots when they’re sitting on the grocery store shelf. It might be our only chance to eat them!

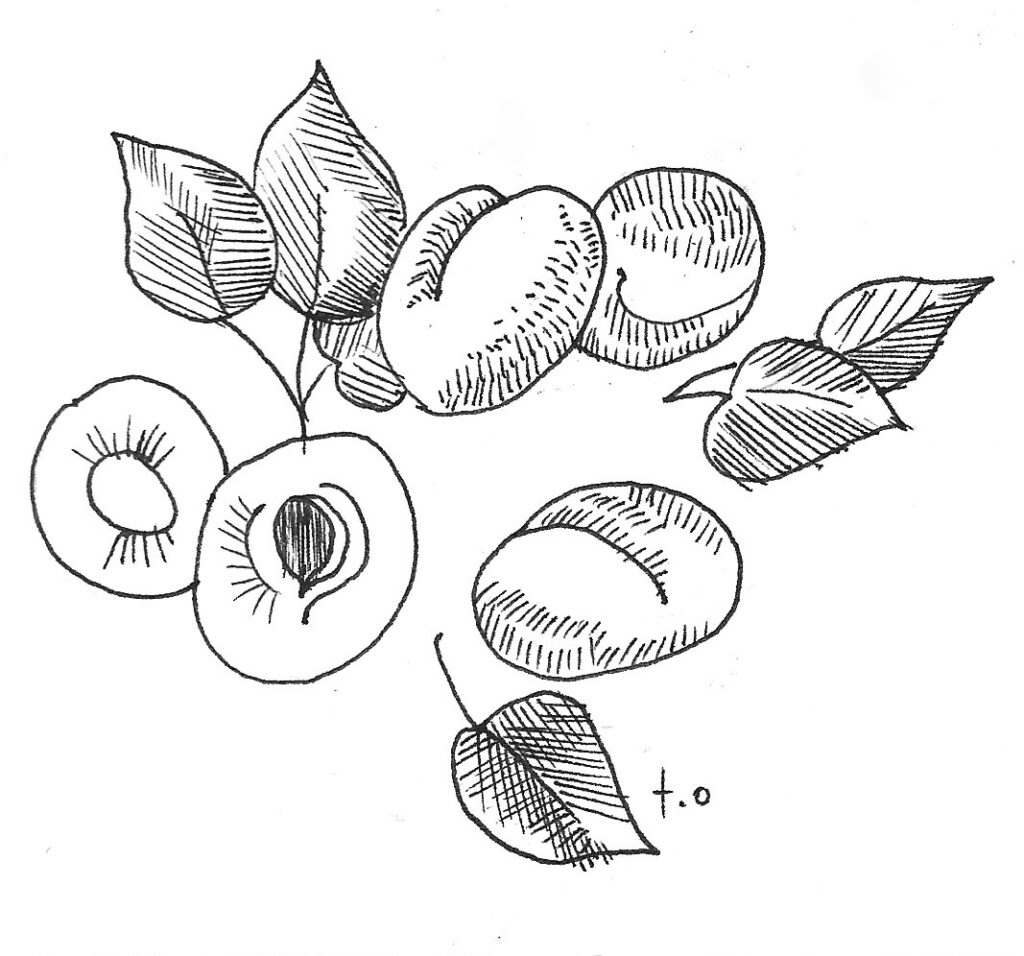

Apricots are a stone fruit along with peaches, plums, cherries, almonds and nectarines. Stone fruit belong to the Rose family and are included in the genus Prunus, containing over 400 species. Growing stone fruit in the Northeast presents a list of pest and disease challenges and, unfortunately, apricots are one of the least adapted to the northern New England climate.

Apricots have grown in central and northern China for more than 4,000 years. Their place of origin has cold winters with temperatures reaching as low as -30 degrees Fahrenheit followed by long and dry growing seasons. They were eventually brought to the Middle East where the bulk of the world’s production exists today. It was not until 70 to 60 B.C. that they were planted throughout Europe. Due to selections made over time, the apricot adapted to the mild Mediterranean climate. These strains were brought to California by the Spanish and are largely what is grown in commercial orchards today. Ninety-five percent of apricot trees grown in the United States, roughly 9,000 acres, are in California. Most of the apricot trees for the U.S. nursery trade are grown here as well.

Growing Conditions

Contrary to what it may seem, the species is actually quite cold hardy. Winter hardiness is a factor but not the main obstacle to growing apricots in Maine. It’s the freezing and thawing in late winter and early spring that damages trees in colder areas. As the trees break out of dormancy, they become less hardy and unequipped for handling late spring frosts. Once the sap in the trunk begins to thaw on warm days, a cold snap at night can cause the tree to suffer winter injury or death when the sap freezes. This happens because many cultivars from California have low chill hour requirements, which is the amount of time they need to spend between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit before breaking out of dormancy. Hardier trees require more chill hours, keeping them dormant longer. Trees suited to warmer climates will begin to wake up once temperatures warm because they have already accumulated the number of chilling hours they need. This is true of many apricot cultivars.

While freezing and thawing also occurs in western regions, there is less humidity and precipitation than in the Northeast, where sites may also have heavier soils. Apricot trees don’t tolerate poorly-drained soils or excessive moisture around their root systems as well as plums or peaches. Wet ground, humid conditions and drastic temperature fluctuations are a brutal combination for apricots.

Cold-Hardy Varieties

One of the best sources of information on cold-hardy apricots is Bob Purvis, owner of Purvis Nursery and Orchard in Homedale, Idaho (plant hardiness zone 6b/7a). As the chair of the Apricot Interest Group of the North American Fruit Explorers (NAFEX), he has been compiling trial results from every region of the country for over 20 years. In NAFEX’s informative quarterly journal, called Pomona, he has reported Debbie’s Gold, Brookcot and Westcot fruiting in central Minnesota (zone 3) with temperatures reaching down to -41 degrees Fahrenheit! Yet even these extremely hardy cultivars don’t seem to grow as easily in Maine due to higher humidity.

In an effort to broaden the gene pool and introduce varieties for the East, breeding programs at Cornell, Rutgers University and Agriculture Canada have sought out strains of Prunus armeniaca in central China, where the largest selection of apricot genetic diversity exists in the world. One of these is a very cold-hardy subspecies called Manchurian apricot (Prunus armeniaca var. mandshurica) that has been used in breeding to improve hardiness.

Manchurian apricot is also the hardiest rootstock available for grafting and is better suited to northeastern soils than rootstocks grown in California. Some of the cold-hardy disease-resistant cultivars that have been released out of these programs include the Harrow Series developed in Ontario, with names such as Harogem, Harcot and Hargrand. Cultivars from the Harrow Series are now being grown for commercial markets in western New York. Rutgers has focused on disease resistance to fungal pathogens and has released Jerseycot, Ilona, Sugar Pearls and Early Blush. All are hardy to -30 degrees Fahrenheit and are more resilient to spring frosts than more common commercial cultivars.

If you’re fortunate enough to have a location where an apricot survives a couple of winters, the next daunting challenge is early bloom time. With low chill requirements, trees start to bloom as soon as temperatures begin to warm. In New England, this leads to flowering in late April and early May, when nighttime lows can easily damage flowers. In northern New England, it is advisable to plant varieties that specify a late bloom time in their descriptions. Additionally, planting on the north or east side of a slope will delay flowering and allow air drainage away from the orchard. Some of the late-blooming varieties Purvis recommends include Haroblush, Alfred, Henderson, Hoyt Montrose, Montrose, Zard, Tomcot, Precious and Sugar Pearls.

Fostering Microclimates in Maine

Despite all the challenges, it’s not completely hopeless for apricots in Maine. While traveling down Congress Street on Portland’s Munjoy Hill in the middle of summer, you might come across a large apricot tree loaded with golden yellow fruit. The tree is said to have been planted from a pit in the 1980s, making it close to 40 years old. Edgewood Nursery owner Aaron Parker says the tree annually bears decent crops of good-quality fruit. Parker collected seed and propagated seedlings from the tree a few years ago. They are now planted in the East End’s Mt. Joy Orchard, not far from the parent tree. The good news is they appear to be doing well so far. It’s a great example of how apricots are more site-specific than other tree fruits. If you want to grow apricots, look for a local tree that is surviving and bearing fruit, and graft a new tree from it. Or plant the pits.

It’s worth noting that areas in southern and coastal Maine are at a regional advantage because of milder temperatures and longer growing seasons. Well-drained soil and protection from harsh winter wind should always be considered when siting an apricot. It’s possible that some urban areas will have better winter protection due to thermal mass from surrounding buildings and pavement. Maybe this is part of the reason the tree on Munjoy Hill has been producing fruit for decades now. The tree also happens to be situated within a mile of Casco Bay where the temperatures are buffered by the ocean.

In Parker’s nursery trials in Falmouth, fungal issues have been the biggest challenge. Planting trees on the upper side of a slope where there is adequate airflow will help. Growing apricots from seed is likely to be more successful than planting cold-hardy cultivars. Trees from seed are often quite vigorous and more adaptable to different environments, partially because they do not go through the stress of being dug, grafted and transplanted. In colder regions, fruit growers have long been aware of the advantages of growing stone fruit “on their own roots” for improved resiliency. With seedlings there is no guarantee on the quality of the fruit; however, there is always a chance of finding an excellent new selection! Seedlings of self-fruitful cultivars will often be similar, though not identical, to the parent. Planting trees from seed is a long-term project that can require a considerable amount of time and space, but is also fun and can be deeply rewarding.

Cold-hardy seed and trees can be sourced from mail-order nurseries such as Burnt Ridge Nursery & Orchards, Schlabach’s Nursery, Cummins Nursery and One Green World. Planting pits from cold-hardy cultivars like Zard and Precious will likely be more successful than a pit of a Californian apricot that came from the grocery store. Locally, seed and trees can sometimes be bartered and traded at events held by the Maine Tree Crop Alliance, a local organization with a focus on growing edible tree crops of all kinds. A limited supply of seedlings of the Munjoy tree are sometimes available at Edgewood Nursery. Trials of seedling trees and cultivars are still needed statewide, especially with a changing climate that might make it easier for them to grow here. By continuing to share our results, we can continue to learn from each other and maybe someday eat apricots from Maine.

Lauren Cormier is an organic gardener with a trial nursery and orchard in Palermo, Maine.