|

| A red oak crop tree with double flagging surrounded by competing red maple, oak lacking quality and diseased beech (not pictured) marked to be cut. |

|

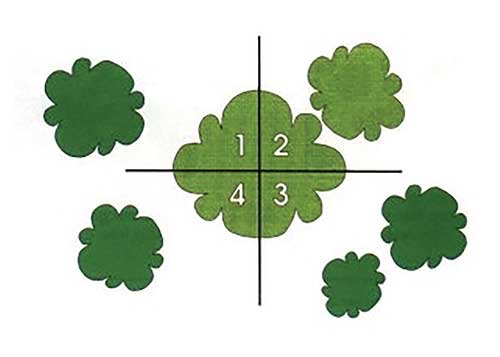

| Crown view of the same red oak crop tree. Note the crown competition and lack of available growing space. |

|

| “The crop tree crown in the center of this illustration has been separated into four quadrants, or sides. A free-to-grow rating is determined by evaluating each side for competition from neighboring crowns. This crop tree is free to grow on three sides.” From “Crop Tree Management in Eastern Hardwoods” |

By Noah Gleason-Hart

Photos by the author

As farmers and gardeners we understand that plants need three things to grow: water, nutrients and light. In our gardens we can add compost and grow cover crops to enrich our soils, and we can irrigate to provide water during dry spells. When we extend our view past the edges of our fields and consider managing our woodlots, our management tools are more limited. Irrigation and fertilization are not feasible and probably not ecologically advisable in the forest. Instead, as forest managers our primary tool for encouraging growth is to use a process called thinning to reallocate existing growing space and light resources to trees we want to grow.

One method of thinning, called area-wide thinning, removes trees from the whole stand to reach an optimum tree-per-acre density based on basal area measurements. When done well this method removes wood lacking quality and leaves all the trees in the stand with more room to grow. However, it requires such specialized tools as a cruising prism as well as training in forest measurements.

In contrast, crop tree management (CTM) identifies valuable individual trees and then focuses growth on these trees by cutting direct competitors while leaving the rest of the forest untouched. It’s an accessible method that you and I can use to start actively managing our woodlots.

Although the word “crop” implies that CTM is a tool for producing forest products, that is not necessarily the case. In a CTM system, you, as the landowner, define “value” based on your objectives. Your crop does not necessarily have to be logs headed to the mill; it could be wildlife habitat, old-growth stand characteristics, water quality or all of these objectives.

If your primary objective is timber production, select crop trees that are commercially valuable species with straight, branch-free lower trunks. Tree vigor and crown size strongly correlate with nut production, so if your primary goal is wildlife management, select trees that produce a hard mast, such as oaks or hickories with large crowns. If your goal is to develop old-growth stand characteristics, you can reintroduce large-diameter trees to your forest faster by increasing the growth rate of long-lived species. Rather than extracting all the trees you cut, you might consider leaving some on the ground to replicate the large quantities of coarse woody material found in late-successional forests.

Regardless of your specific management goals, you want to retain trees that are healthy and structurally sound. A favorite mantra of one of my forester friends is that when you are selecting trees to grow, you should “let the crowns do the talking.” A healthy, competitive tree that will respond well to increased sunlight will have a robust, full crown with few dead limbs. Although species-specific exceptions apply, a tree growing under the main canopy in a stand of similarly aged trees could be stunted and may not grow well after release. Instead choose trees that are already growing and competing in the upper canopy; they’ll respond to increased growing space with faster growth.

The next time you’re walking in your woods, bring a roll of flagging tape (biodegradable options are available). When you see a tree that is healthy and vigorous and could help meet your objectives, flag it. If you’re truly engaging with your woodlot, you’re operating on tree time, not a short human timescale, so you needn’t come back tomorrow with a chainsaw in your hand. Instead go back to the tree a few more times. Does it have any defects you missed on your first visit?

If, after your second or third visit, you still believe that this is a tree you want to keep, look up. In a crop tree release, you want to ensure that at least three sides of your crop tree are free to grow. To determine this, split the crown into four imaginary quadrants (see illustration); are crowns of other trees touching the tree you’d like to keep? These competing trees are the ones to cut.

However, moderation is key. If you let in too much light, your crop tree may respond by sending out branches from a previously clear trunk. These are called epicormic branches, and they lower timber value, so cut just enough to create space for your tree.

The condition of your woodlot will determine how many crop trees you have per acre. In some cases you may have just a few, while in others you may have as many as thirty. Your objectives also influence how many trees you select. If you prefer to retain a dense forest with significant canopy closure for ecological, carbon or aesthetic reasons, select just a few trees per acre to release. This will accelerate the growth of your best trees but leave the majority of the stand untouched. If you are interested in maximizing high-value growth per acre, you could select more crop trees and have a more open stand post-harvest.

If you have questions about tree selection or harvesting, bring in a licensed forester. These trained professionals can write a comprehensive plan to help you manage your forest to meet your objectives. If you don’t have the knowledge or equipment to carry out a crop tree release harvest yourself, a forester can also help you locate a reputable logger. In some cases the value of wood removed is high enough to include CTR in a traditional stumpage sale. In other instances you could consider hiring a practitioner to complete the work in a fee-for-service hourly arrangement. In either case funding may be available from the Natural Resources Conservation Service to help defray your investment in the quality of your future forest.

Finally, remember that if you extract the wood you cut, you must minimize damage to residual trees. Scarred trunks from careless skidding or broken tops from imprecise felling may heal over, but they will leave internal defects that reduce timber value and tree longevity. The cost of logging damage to residual trees quickly outweighs any growth benefit from increased growing space. If you don’t have the skills to do careful work or can’t find a conscientious contractor, don’t cut at all. A single harvest has decades-long repercussions, so it pays to proceed cautiously.

For more information and sample crop selection criteria, consider reading “Crop Tree Management in Eastern Hardwoods” by Arlyn W. Perkey, Brenda L. Wilkins and H. Clay Smith, USDA Forest Service, 1993 (available as free download online).

Noah Gleason-Hart is MOFGA’s low-impact forestry specialist. You can contact him at f[email protected].