|

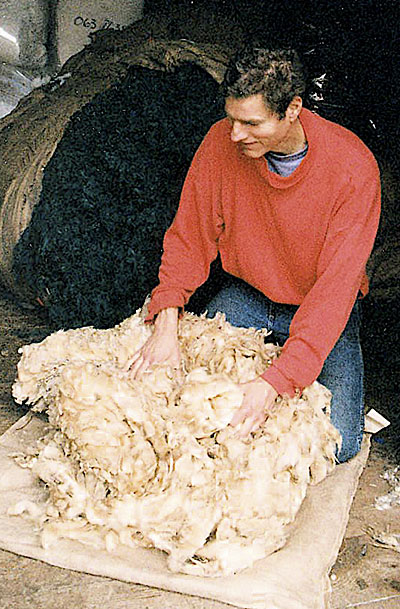

| David Ritchie sorts wool at the worker-owned Green Mountain Spinnery in Putney, Vermont. Photo courtesy of Green Mountain Spinnery. |

by Tim King

At the Green Mountain Spinnery in Putney, Vermont, shepherds can have their animals’ fleeces spun into certified organic yarn, GREENSPUN yarn, or yarn spun using conventional, petroleum-based spinning oil. Encapsulated within those three options is the story of the development of this 25-year-old wool processing and spinning plant.

“Throughout its history, the Green Mountain Spinnery has worked to sustain regional sheep farming and to develop environmentally sound ways to process natural fibers,” says David Ritchie, one of the 12 workers at the worker-owned company.

During that 25-year history, Ritchie says that he’s seen most flocks in New England get smaller – but he’s also seen many shepherds develop a better sense of the value of quality fleeces and savvier approaches to marketing wool.

As an example of the Spinnery’s work to help sustain those small, local flocks, Ritchie mentions the yarn called The Colors of Montgomery Center. Four Montgomery Center, Vermont, shepherds and artisans decided to pool their similar fleeces and then asked Green Mountain Spinnery what type of yarn could best be spun from them.

They also wanted to blend some fiber from Angora goats with the wool. That was no problem, since the Spinnery specializes in blending wool and fibers such as alpaca, mohair and cotton. So David and the shepherds decided on a yarn.

Then, since Green Mountain Spinnery does not dye fibers, the shepherds approached the local community garden club and found members who were delighted to grow plants that would provide the desired natural colors. “The skein I have here is colored with a dye from cosmos flowers,” says Ritchie. “It made a beautiful golden colored yarn. They tell me you can get one color from a species of flower one year and a somewhat different color the next year. They named the whole project The Colors of Montgomery after the town. They actually have a cooperative shop near Montgomery Center called Mountain Fiber Cooperative.”

|

| Patterns and wool from the spinnery. Photo courtesy of Green Mountain Spinnery. |

One option that the Spinnery offers to creative shepherds who want a product like a blended yarn dyed with cosmos flowers is GREENSPUN yarn, which is scoured with non-petroleum-based soap and spun with a vegetable-based spinning oil developed by a chemist especially for Green Mountain Spinnery. Additionally, no chemicals are used to bleach, shrink or mothproof the yarn, and the Spinnery uses a water recycling system.

These are the same processes used to create the Spinnery’s certified organic yarns – with two exceptions. “To be certified organic, shepherds need to feed their sheep certified organic grains,” says Ritchie. “It’s very hard to find certified organic feed in Vermont and New England. A lot of times it has to be shipped from Canada or somewhere else,” which may not be economically sustainable for the farmers.

Additionally, certified organic processing requires that fresh water be used with each new batch of yarn to be washed. The Spinnery has worked hard to develop a water cleaning and recycling program and finds the water requirements of organic certification to be somewhat wasteful.

Maine Connection

|

| The MOFGA-certified organic Noon Family Sheep Farm in Springvale, Maine, supplies organic wool that Green Mountain Spinnery turns into certified organic yarn. Here, lambs strip graze at the Noon farm. Jean Noon photo. |

The Noon Family Sheep Farm, a MOFGA-certified farm in Springvale, Maine, supplies the organic wool that the Spinnery turns into certified organic yarn. “We produce all of our own hay off our own fields and two other small local farms,” Jean Noon says. “Our grain is very expensive and currently is purchased in bulk from Blue Seal Feeds. We have a large bulk bin that the grain is blown into in 3-ton lots. We would prefer buying directly from a farmer but have not yet been able to make a solid connection.”

Noon, who raises a flock of 70 Columbia-Rambouillet-Leicester-Suffolk cross ewes, has had her farm certified organic for more than three decades. “We have farmed without chemicals since 1971,” says Noon. “We attended one of the very first meetings of organic farmers that grew into MOFGA. When the certification program was established, we decided to participate in it as a gesture of support for MOFGA. The recordkeeping is cumbersome but has made us better farmers by forcing us to keep track of what is happening on the farm.”

With the advent of USDA organic standards for meat and wool products, The Noon Family Sheep Farm, like farms across the country, gained the opportunity to supply new markets – along with the challenge of meeting the new standards.

David Ritchie sees an increasing market for yarns labeled as organic or with other “green” labels. The GREENSPUN label, with its emphasis on low energy use and locally produced inputs, is particularly interesting to certain market niches, he says.

“This whole local thing is so important right now,” he notes. “When we started this in the early ‘80s, we focused on it because we thought it was the right thing to do. Since then people have grown to understand the value of organics; but now, if the organic input has to come from Argentina, maybe locally produced makes even more sense to knitters and weavers.”

Quality Advice

Since the Green Mountain Spinnery does custom processing and makes and sells its own line of yarns, Ritchie believes that the marketing advice the company can give to a prospective customer can be useful to shepherds who want to reach those knitters and weavers with their products.

According to the Spinnery’s Web site, quality yarns are made from fleece and fibers that are:

clean and free of chaff, burrs, tags

well-shorn with few second cuts, and with short belly wool discarded

staple length from 2.5 to 5.5 inches

stored dry, preferably in burlap bags or cardboard boxes and not in plastic grain bags

free of moths and moth damage but with no mothballs

a blend of fibers that are not too coarse or slippery for the Spinnery’s machines.

“When people call I ask them what kind of sheep they have and I try and find out what they know,” says Ritchie. “I also share what we know. We have our own yarns, and we know something about the market. Every flock is different, and many shepherds are very particular about what they want. We take a lot of pride in finding what is right for a particular flock and shepherd.

“But sometimes I tell them they are never going to get there with the sheep they have. I may even advise them on what breeding stock they need to get what they want. On the other hand, I might say it’s a type of fiber we can’t do anything with, because it’s too long or too lustrous. We have limitations because of the type of machinery we have.”

The Green Mountain Spinnery’s machinery is for wool but is not suited to making worsted yarns. “The machinery for the woolen system produces a more lofty, less dense product,” Ritchie explains. “Worsted is more combed, and the machinery makes the fibers run parallel. The worsted machinery can handle longer fiber. Our equipment can handle a staple length from 2.5 to 5.5 inches. Lincoln long wool is one of the breeds that will give us a problem.”

The Spinnery’s 41-foot-long carding machine, with its two main cylinders, is the primary limiting factor. “It’s our biggest machine, but it’s a little smaller than the big mills, which have cards with four cylinders,” Ritchie says. “That means our yarn isn’t quite as processed. The more you process a yarn, the less life it has. Our yarns have a lot of life in them.”

The Spinnery’s Web site says that on average, 100 pounds of raw wool will yield roughly 55 pounds of yarn. “Both the breed and the processing affect the yield,” he adds. “How you feed also affects yield, because if you load [the sheep] up with grain, they load up with grease. Then you lose a lot when we wash, plus we may have to put it through twice and it will cost you more.”

The cleanliness of wool can affect both yarn yield and quality. “We don’t tell people they have to jacket their sheep, but there is a lot to be said for getting your wool as clean as possible,” says Ritchie. “Working on your feeding system helps keep the chaff out of the fleece. Clean wool makes a more beautiful product. Also, we charge a cleaning fee if we can clean it. If we can’t clean it, we send it back.”

Jean Noon, the Spinnery’s organic wool supplier, who also sells yarn and fleeces to hand spinners, has developed a system for keeping fleeces clean. “The sheep are kept outside all summer without blankets. I shear them myself and skirt them extensively as needed. I also try to get them sheared early in the winter, before they have been eating much hay and getting the hayseed into their fleece. The fleeces are packed into burlap wool bags and kept clean and dry until sold.”

For more information, contact the Green Mountain Spinnery, www.spinnery.com , 1-800-321-9665, or The Noon Family Sheep Farm, www.jeannoon.com.

About the author: Tim King and his wife, Jan, own Maple Hill Garden in Long Prairie, Minnesota. They also publish La Voz Libre for the local community.