|

|

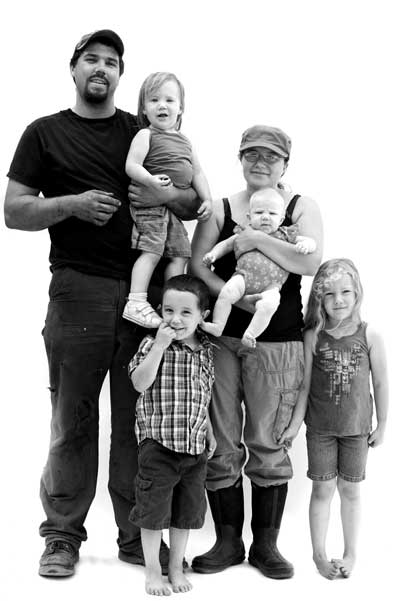

The Rusted Rooster Farm family, left to right (with ages as of Oct. 2017): Sean, Chloe (3), Jackson (5), Sandra, Lacey (17 months) and Shannon (6). Photo by Lily Piel |

|

|

Mowing a cover crop of peas and oats for cattle feed with an 826 International. Photo by Sean O’Donnell |

|

|

Sean at work in his John Deere 3300 combine. Photo courtesy of Sean O’Donnell |

|

|

Combined grain is transferred to the back of a dump truck. Photo by Sean O’Donnell |

|

|

Grain moves through a Clipper 27 grain cleaner. Photo by Sonja Heck-Merlin |

|

|

A Forsburg 10-M gravity air table provides the final step in cleaning grain at Rusted Rooster Farm. Photo by Sonja Heyck-Merlin |

|

|

Some of the 2017 grain crop, stored in 1-ton vented nylon tote bags. Photo by Sonja Heyck-Merlin |

|

|

Sean with some of the 2017 straw crop. Photo by Sonja Heck-Merlin |

By Sonja Heyck-Merlin

“I was born with a green thumb,” says farmer Sean O’Donnell, 28, of MOFGA-certified organic Rusted Rooster Farm in Piscataquis County. “As much as we tried to clean it up, it just wouldn’t come clean.”

O’Donnell’s grandfather was a potato farmer in Houlton, and although the farm became inactive before Sean was old enough to be involved, he has fond memories of the land, especially the tractors. Picture him as a toddler, captivated by the clamber and power of his grandfather’s equipment, and then as a child, trying to convince his parents that, surely, he was old enough to drive a tractor.

“I have just always liked farming,” O’Donnell explains. His family supported his interest in agriculture through his entire K-12 homeschool education, providing him with hands-on opportunities to learn about raising livestock and growing crops. The family’s first animals were chickens, and after a few years no one but Sean wanted to take care of them. Likewise with the garden: “When I was 12, the garden ended up being mine because no one else wanted to work in it,” recalls O’Donnell.

The family moved from Dixmont to its current Parkman location when O’Donnell was 10. Shortly after that, he began working for a local farmer who raised replacement dairy heifers and dry hay. By age 15, O’Donnell had a team of oxen and was interested in putting up his own hay to feed them. He purchased his first tractor, a two-cylinder John Deere 420, and some haying equipment. “That was the start of the iron disease,” he says.

He was able to raise some of his own replacement heifers at his employer’s farm, and the sale of those heifers allowed him to make a down payment on a 43-acre parcel of land adjacent to his parent’s land. That would become Rusted Rooster Farm – so named because for as long as O’Donnell can remember there have been hens running around, and “Rusted” because of his affinity for old rusty equipment.

“I also started working at Raymond Harveys in Dover-Foxcroft at that time,” he says. “Basically, I was a shop grunt, but it was a good place to start learning about equipment.”

Still employed part-time at Harvey’s, O’Donnell said it is a great avenue to continue learning about mechanics, and an opportunity to gather information from Harvey’s diverse clientele.

After purchasing his land, he began renting more hay ground and grew about 5,000 pounds of carrots a year, which were marketed to Crown of Maine. During that time he also met Sandra, now his wife, through connections of his mother, Cindy O’Donnell, a well-known central Maine midwife. The couple has four children, ages 6 and under.

Sean’s interest in grain growing grew out of his need to improve the few hundred acres of hay ground that he covers each year. About 75 percent of Rusted Rooster’s land base is used for hay, with most of that rented ground. O’Donnell says, “I saw grain growing as a chance to improve my really rough hay fields.” Rejuvenating abandoned or fallow land with a sequence of grain crops is one way to add nutrients and organic matter to the soil, at the same time making the surface of the land smoother and more suitable for haying equipment.

The farm’s sources of fertility are wood ash, manure (both from his animals and imported chicken manure) and green manures. The wood ash and manure are spread with a manure spreader. A 5-acre piece typically receives 30 tons of wood ash (sourced from Herman-based Maine Environmental) and 30 tons of manure. O’Donnell has found that plowing fallow ground and growing grain crops has increased the biological activity of his soil. “Plowing oxygenates the soils at deeper levels, which promotes aerobic bacteria and microbial activity, which releases bound up nutrients,” he says.

His original intention was not to produce grain commercially but to improve the land and grow some grain to feed his livestock. The family has 18 head of beef cattle, 30 sheep and goats, and two Norwegian Fjord ponies – all tended primarily by Sandra and the four children. Growing grain for the livestock proved successful, and then Sean decided to try saving some of their own seed rather than buying new seed annually. From there he realized he could help meet the demand for both locally grown seed and food-grade grain.

“If it has a seed head on it, I will try it,” says O’Donnell as he explains the diverse array of crops he has experimented with: soybeans, sunflowers, flint corn, rye, millet, wheat, barley, hull-less oats, standard oats, peas and buckwheat. “I have, however, had to prioritize what is making money,” he says, so heirloom wheats, oats and rye make up most of the acreage.

In 2017 he planted 83 acres: 18 in wheat, 22 in rye, 3 in barley, 15 in oats, 10 in millet and 15 in sugar snap peas/oats. The 2016 crops were sold almost exclusively as seed through Fedco, but this year he anticipates selling more volume to Maine Grains in Skowhegan.

O’Donnell’s greatest challenge is controlling the noxious wild radish weed, a member of the Brassicaceae family. Others refer to it as mustard. The hundreds of weeds in this family are difficult to differentiate. O’Donnell points out that the type at Rusted Rooster has a shatter-proof seed head that splits open when it’s time to germinate.

“I am really struggling with control strategies,” he says. “Sometimes it seems like the wild radish is the bane of my existence.” He recognized that during his first few years of growing grains, he was “really good at depositing weeds” and now he is “trying to learn how to make more withdrawals from the weed seed bank rather than deposits.”

He seeds with an International 510 grain drill. His first year on a new piece of ground, he plants peas and oats; the following year, a spring grain. He says the first year in a spring grain tends to be pretty clean of weeds. Following harvest of the spring grain, he tills shallowly and immediately plants a winter grain. Only recently has he begun to develop a rotation using this strategy.

“I am curious to see what will happen in the third year by using this rotation,” he says. His goal is for five years of grain followed by five to eight years in alfalfa or a grass/alfalfa mix. Ultimately he would like to develop a market for organic baleage for organic dairy producers.

After the five to eight years, O’Donnell hopes to have some fresh ideas for handling the wild radish challenge when the land is tilled again. “I have one harebrained idea,” he says. “I would like to try a post-emergent flaming that would essentially almost kill the grain crop but at the same time knock down the weeds. The grain would come back, and it would have a head start over the weeds.” Having observed that wild radish seems to thrive where imported chicken manure has been spread, he plans to transition to dairy manure to see if that may also help minimize the weed problem.

Two years ago, O’Donnell traveled to Sweden, where he observed precision-cultivated grain farms. With only a three-point hitch cultivator, he is limited in his ability to cultivate, and he expressed skepticism about being able to effectively cultivate his grain crops. “I know there is no such thing as a silver bullet. No machine is going to fix your problems,” he says. “I think in the end that rotation is more important. I am also short on time and [on] tractors during cultivation season because of haying.”

Weed challenges aside, O’Donnell has combined 10 tons of rye and 10 tons of wheat this year with his 70 horsepower 3300 diesel combine. He refers to the purchase of his first tractor as the beginning of his “iron disease,” but his longstanding interest in machinery combined with his mechanical aptitude have allowed him to customize his combine to produce clean, quality grain crops.

“I have hacked out access doors everywhere,” he says, in order to clean out one grain crop before harvesting the next. “I think one of the biggest problems with organic grains is that people do not adequately clean out the combine. I pride myself in taking a full day to clean out the combine so there are no seeds contaminated from the previous crop. If you get one oat or rye seed, it will just multiply and choke out an heirloom wheat.” Oats and hull-less oats also easily contaminate one another.

From the combine, the grain is loaded into a dump truck with pavement doors in the back. If the grain had lodged and the combine head was run onto the ground, the grain must first be run through a destoner. If there are no stones, it enters an auger and then runs into a Clipper 27 grain cleaner. Lastly it enters another auger and then a Forsburg 10-M gravity air table for the final stage of cleaning. Gravity air separators, also known as gravity separators or density separators, use a combination of air for weighing, vibration for fluidizing and conveying, and tilt (or slope) for separating. Gravity separators are used to separate any kind of kernel and granular product of almost identical size but with different weights.

After this process, the grain goes into 1-ton vented nylon tote bags, which are stored in the greenhouse. Rusted Rooster relies on a semi-passive drying system versus an active drying system, which relies on heat from an electric or gas source. B&W brand aeration tubes are screwed into the grain, and a large fan is placed on the top. O’Donnell removed the original fans from the tubes and replaced them with 1 horsepower fans purchased from the closed Bucksport paper mill. “The original fans didn’t move enough air through the tote to dry the grain fast enough,” he says.

“The fans are only turned on when the humidity is low,” he explains. “Humidity is the biggest factor in drying grain. In Maine in the autumn, if you don’t babysit your fans, your grain will only dry to 15 percent, which the markets won’t accept. The feed market might accept it, but not a crop that is intended for human consumption or the seed market. It has to be 13.6 percent or less.”

Gauging harvest time is a challenge. While lodging is a danger, so is harvesting grain that has not dried down to around 15 percent moisture. This year he chose to leave a field of mature rye standing for a few extra weeks to save drying time in the totes. On the other hand, he harvested a field of wheat earlier than he would have liked, due to weed pressure. “The moisture won’t go down that much with so much green weed matter in it,” he says. “The moisture actually increased from 15 percent to 22 percent just from sitting in the combine hopper because of the green matter.”

In 2016 Rusted Rooster’s grain sales exceeded its hay sales for the first time – approximately two-thirds of its gross revenue came from grain and one-third from hay and straw. “Battling the weeds and weather can be a struggle,” says O’Donnell, “but I have a can-do attitude and look at everything as a challenge that can be overcome.”

The net of this positive attitude and perseverance is tons of beautiful, nutritious and aromatic grains. O’Donnell provides a unique opportunity for us all to take a piece of Rusted Rooster’s farm and nurture it in our own fields, gardens and kitchens.

About the author: Sonja Heyck-Merlin and her partner Steve Morrison raise cows, gardens, grass and kids on Clovercrest Farm in Charleston, Maine. Clovercrest Farm, a second-generation dairy farm, milks 90 Jerseys and has been MOFGA-certified organic since 1995.