By Holli Cederholm

Organic agriculture has a plastic problem. The problem is, said vegetable producer Lincoln Fishman, plastic is useful. Drip tape for irrigation, bread trays for harvest, and perforated bags and woven plastic feed sacks are all “beautiful inventions,” he told a room of growers during a session on plastic reduction at MOFGA’s Farmer to Farmer Conference held in Carrabassett Valley, Maine, last November. “The truth is,” he quipped, “I love plastic.”

Plastic shows up all over vegetable farms, including on Fishman’s Sawyer Farm in Worthington, Massachusetts. Plastic film covers high tunnels for season extension, and sheets of plastic mulch have been widely adopted by organic farmers as a weed-suppression alternative to herbicides sprayed on conventional farms. Plastic mulches blanketing production fields do double duty, warming the soil for heat-loving tomatoes, melons and peppers. White polypropylene fabric, sold under brand names such as Reemay and Agribon, is another trusty staple. Row cover is equally effective at buffering early plantings of kale from frost as it is at shielding broccoli from hungry caterpillars.

From seed to sale, plastic is integral to many farms. Plastic, which is cheap, widely available, and, yes, useful, has become ubiquitous in farmers’ market displays: from bags that help retain the moisture of lush baby greens to clamshells cradling cherry tomatoes as delicate as eggs. Farmers’ dependence on single-use plastic packaging spiked with increased consumer concerns at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. “People want everything in a bag,” said Fishman. “The idea of how much trash we can make in safety’s name … ” he trailed off, shaking his head.

Plastic on farms does not start out as trash. Every piece serves a purpose, and usually the farm’s bottom line. Plastic can equate to increased profitability — a high tunnel can lead to earlier sales or increased yields; insect exclusion netting can cut crop losses; and landscape fabric can save labor dollars funneled into endless weeding. Further complicating matters, plastic is a handy tool in farmers’ climate-resilience toolkit. For example, crops grown under cover may be cushioned from temperature extremes or an intense weather event.

While plastic can be practical, a product’s intended use is often short-lived — and the material itself is not. Black plastic mulch, for example, is usable for one season. Before the snow flies, farmers rip it from their fields for disposal. Not all products are destined for the dump after a single use. Many farmers try to extend the life of plastics, reusing seedling plug trays, irrigation lines, and even the more fragile row cover, but this isn’t without its own set of problems. Plastic, in a general sense, is both incredibly durable and prone to degradation. With use, plastic breaks into smaller particles, termed micro- and nanoplastics depending on size, that don’t ever fully go “away.” On farms they can pass through plant roots and into the fruits and vegetables we eat.

Fishman points out that recycling is also complicated. Only 10% of plastic produced globally has been recycled. Recycling pitfalls are exacerbated when it comes to agricultural plastic, which can be too weather-worn or dirty to have its life extended. Greenhouse film (specifically clean and dry low-density polyethylene #4) is one of the exceptions, and even then it cannot be recycled indefinitely.

Plastic is piling up — in our oceans and waterways, in landfills, and on our farms — becoming environmental and human health hazards. While Fishman recognizes the utility of plastic, and is not ready to ditch plastic altogether, he feels that reducing reliance on it is the right thing to do. He quoted Rabbi Tarfon, saying, “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.”

A Series of Small Wins

“I feel like I’m a conventional farmer who’s basically like, I don’t know how to stop using Roundup. I’ve read all the studies. I’ve talked to the people. I’ve had my kid drink it by mistake and taken him to the ER, and I don’t know what else to do next year. What am I going to do? That’s a little bit how I feel,” said Fishman.

At Sawyer Farm, which grows a handful of crops for wholesale markets, reducing plastic is a “series of small wins.” Buying potting soil in bulk “sling” bags versus smaller perforated bags is a win. So is reusing existing plastic, such as rigid plastic crates, as much as possible.

Fishman calls drip irrigation — thin black tubes of plastic that dole out sips of water at the base of a crop — one of his “worst offenders.” “I don’t love the plastic packaging of produce,” said Fishman. “It all pales in comparison to just how many trash bags I fill with drip.” He cut his drip tape needs — and costs — in half by running drip on every other bed. Now he moves the drip lines, by foot, on an alternate-day watering schedule, which fortunately works well for the farm’s soil type.

More wins come in the form of cultural practices. Sawyer Farm tries to direct seed as much as possible, as their transplants are heavily reliant on plastic — from the trays they’re seeded in to the high tunnel that provides a jump on the season.

In their no-till beds, which, admittedly, are covered in plastic landscape fabric, row cover isn’t necessary to keep the bugs at bay. Fishman says that’s because there is more habitat for pest predators that naturally control many of the insects prone to damaging the cash crops. To encourage their presence, he only mows one side of the bed at a time. His goal is for the vegetable production zone to mimic nature more closely.

The permanent no-till beds are spaced 30 feet apart in pasture. Fishman mows the pasture, raking the plant material onto the beds with a hay rake to increase fertility and suppress weeds. The approach allows for tall swaths of grass — prime habitat for pest predators — to grow between crop rows. “It’s just flipping the pollinator strip and the production strip, just inverting the relationship there, so it’s primarily an ecosystem that has some vegetables growing in it,” said Fishman.

Another trial in the works is a multi-year living mulch system. In July of year one, he uses a broadcast seeder to sow Dutch white clover, at a rate of 20 to 40 pounds per acre, into bare soil of what will become a cash crop field the following year. (The clover needs to be seeded eight weeks before the first frost to reliably overwinter.) In year two, he mows the clover and transplants seedlings into the cover-cropped ground with a modified mechanical transplanter. The third year is another planting year, and then the system is tilled to “reset” it, as perennial weeds start to creep in. For in-season mowing, Fishman relies on a self-propelled commercial push mower. He cautioned not to expect it to last more than several years but likes that it is easy for anyone on the farm crew to use.

The first year of his trial, 2019, he transplanted cabbage, hemp and winter squash into the mat of clover. “It was weirdly successful,” he said, noting that his cabbage yielded nearly 30,000 pounds to the acre. Fishman didn’t use row cover or insect netting for any Brassicas grown in the clover, and the disease pressure was comparable to those grown in bare ground. The yield was about 75% in the interplanted plots, but the tradeoff seemed worth it. “It’s green and 100% covered the whole time,” said Fishman.

Since then, tomatoes, other Brassicas, garlic and beans have proven successful. In many cases, Fishman said, yields were reduced, but labor was reduced as well, so profitability was equivalent. All the while, he added, the clover worked to increase soil health. Other trials were not as successful, including cucumbers and peppers (he suspects the well-shaded soil was too cool); lettuce (lots of slug damage); oilseed sunflowers and corn (didn’t reach full maturity); and potatoes (low yields). Still, Fishman is hopeful that this system shows promise — not just for his crop rotation, but for other farms as well. With others, Fishman started Momentum Ag to pay farmers “to grow knowledge” through collaborative farm-based trials, such as incorporating living mulch.

Plastic Reduction at Murphy Family Farm

Sean Murphy also spoke at the Farmer to Farmer Conference about reducing plastic use on the farm. He has never laid black plastic mulch on the 4 acres he cultivates at Murphy Family Farm in Freedom, Maine, and has been looking for other ways to avoid plastic.

In 2021, Murphy made the decision to ditch row cover after experiencing quality issues with the product. “It was constantly unraveling these tiny, tiny, tiny threads of plastic everywhere,” said Murphy. Additionally, his farm site is windy, making row cover a challenge for the farm’s team of two to roll out and keep in place. It also doesn’t fit easily into his system of tractor cultivation for weed management. The frustration of working with row cover was compounded when he considered the waste involved. At the end of a season, farms across the country are shelling out labor dollars to bag it up and more money to send it to the landfill. For Murphy, it just didn’t add up.

While Murphy Family Farm isn’t certified organic, they don’t use sprays of any kind, including for pest management. Many organic growers, certified or not, lean on floating row covers to reduce reliance on pesticides approved for organic. Without row cover, Murphy had to contend with increased bug pressure on certain crops at different points in the season. For instance, he could no longer reliably grow early-season Brassicas, including radishes and salad mix, whose tender foliage are a flea beetle favorite. To fill in his display at local farmers’ markets, Murphy planted asparagus, a crop that has become the backbone of his spring income. “The asparagus is great — no row cover, no black plastic, and no early tillage. So, we kind of get the best of all worlds there,” said Murphy.

Another Brassica pest that can be challenging to manage without sprays or physical exclusion is the cabbageworm. “Nobody wants a nice fresh head of broccoli with six little friends inside,” said Murphy. Through experimenting with different varieties, he has found that Piracicaba, a non-heading broccoli, grows well without row cover.

Murphy acknowledged that sometimes he has a hard time thinking beyond plastic. “I can’t just say, ‘don’t use plastic.’ What else are you going to do?”

In 2023, on a whim, he conducted a field trial to see if cedar mulch would deter cabbageworm in his spring-planted broccoli crop. He applied 1 yard of chipped cedar to eight 150-foot beds of broccoli. “It’s just a dusting,” he said.

While one trial in one season isn’t enough to prove the mulch’s efficacy as a deterrent, Murphy reported that he hardly saw any moths on the crop. “There’s a test that the universities do: You stand in one spot for two minutes, you count cabbage moths … and two, I think, was the most I ever counted in this two-minute period. It was, you know, basically nothing.”

For $37 worth of wood chips that will add organic matter to his soil, Murphy thinks it’s an experiment worth repeating — especially with a fall crop when the pest pressure is notoriously higher.

Meanwhile, Murphy is thinking about plastic reduction for the whole farm. Instead of starting seedlings in plastic cell trays, which can be reused but have a tendency to crack and break over time, Murphy uses rigid plastic bulb crates to hold soil blocks. He finds that the gaps in the crates, which he doesn’t line with newspaper, work to naturally air-prune his seedlings. The crates are also used for toting asparagus and potato harvests from the field later in the season.

His propagation house isn’t a hoop house with a plastic skin that needs to be replaced due to solar degradation — or high winds. Plants are started in a 12-by-16-foot Amish-made seedling house, which is constructed with rigid plastic panels rather than less sturdy plastic film. The structure is unheated, so he moves cold-sensitive plants into his 400-square-foot house on chilly nights. The bulb crates come in handy once again, as he can stack them to conserve space.

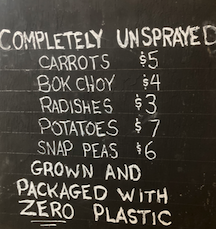

In addition to the crates, plastic shows up in various ways at Murphy Family Farm — mostly in the form of packaging. He described the farm’s market spread: “You’d have the bags of broccoli; you’d have the bags of bok choy. Bag, bag, bag, bag, bag. And nothing kind of looked like what it was.”

Murphy sought out alternatives, keeping an eye on neighboring market displays for ideas, such as green beans nestled in quart containers. He now bunches bok choy — wrapping a rubber band around the heads in the field — instead of bagging the greens post-wash in the pack house.

Part of a successful transition away from plastic, he said, comes down to education in addition to alternatives. While plastic lengthens the shelf life of produce, market farmers wouldn’t need to swaddle every harvest in it if customers chose to eat their food at its peak. “You don’t need to use two-week old lettuce,” said Murphy. He replaced lettuce mix with head lettuce in his crop plan — no bag required. After the shift, some of his existing customers asked, “Where’s your bags?”

Other shoppers saw the produce — the bunches of bok choy and heads of lettuce newly unobscured— and were drawn to the stand. Murphy said, “All of a sudden, they’re buying stuff from me. So, what’s not to like? You know, I’m spending less money, I’m using less plastic, and I’m getting new and very consistent customers.”

This article was originally published in the spring 2024 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.