|

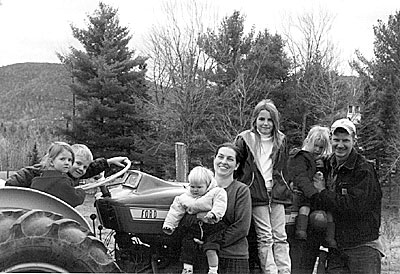

| Morrill Farm is a true family farm, with three generations working together. Here Holly and Dan Perron pose with their five children, left to right: Grace, Laura, Celine, Christian and Catherine. One enterprise on the farm is presenting “living history” events for groups, in which generations of Morrills who started the farm, and their lifestyle, are portrayed. Joyce White photo. |

By Joyce White

In creating a 21st century organic farm, the Perron family – pronounced with the accent on the last syllable – of Sumner has incorporated many elements of a much earlier lifestyle. For starters, two generations share the land – “two entities working together” is the way son Dan Perron describes the operation. The older Perrons, Laurier or “Larry,” and Patricia or “Pat,” bought the 214-acre farm in 1989 when their children were teenagers. Dan, now 31, with his wife, Holly, and their five children live in a separate house on the land and call their operation Sumner Valley Farm.

Before moving to the small, western Maine town of Sumner, the Perrons had operated Larry’s family dairy farm in Lewiston. They were the next to the last farm family to leave the area, Pat says, as one farm after another was crowded out by housing developments and by complaints about farm smells and activities. They had vowed never to leave the family farm, but as the farming community disappeared, they changed their minds.

For three years they sought a location where they wouldn’t be crowded out again. Two farms they chose went to other buyers while they waited for their farm to sell. Then Larry learned of the farm on a dead end road in Sumner that was not actually on the market. Pat had no desire to move that far into the country, but Larry approached the 91-year-old owner anyway.

A special appeal was the fact that commercial fertilizers and sprays had never been used on the land, and when Larry said he intended to create a small family farm using organic methods, the old farmer was convinced to sell. Pat came to see the farm and agreed, reluctantly; their kids were the only farm kids in their school. It was time to move.

|

| Cows are organically raised and are content both outdoors and in at Morrill Farm. Joyce White photo. |

Almost from Scratch

They kept two Jersey cows from their previous herd, which provided rich milk. They started small, raising chickens and selling surplus eggs, meat and butter. “Our farm had always been organic; we just didn’t call it that back then,” Larry explains. One of his goals for the new farm is to eliminate the middleman and to sell directly to consumers.

The farm has grown gradually as Larry has learned the details of farming in a different climate. “It’s only 32 miles farther north, but it’s a whole different world here. The growing season is shorter and the soil is different. It’s been quite an adjustment,” he concedes. In Lewiston, everything was right there – the grain store, the hardware store. Now they have to plan carefully, because trips for supplies or repairs can absorb valuable time.

Larry has used his chain saw to reclaim overgrown fields, work that continues to this day. He bought a sawmill to mill the logs into lumber for new outbuildings, another ongoing project. Stumps remain to rot in the ground and add nutrients to the soil. They now have six wood stoves, including one in the small chapel they built for Sunday use, so Larry and Dan also cut a lot of firewood.

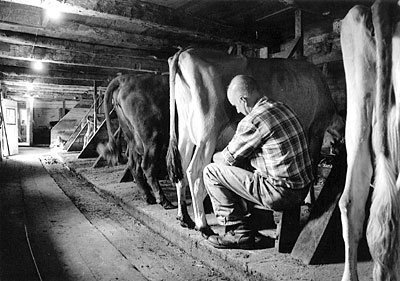

|

| Larry Perron milking the cows at Morrill Farm in Sumner. The multi-generational farm incorporates historic interpretation into its many activities. Photo courtesy Morrill Farm. |

Dan and Holly raise beef, pork and poultry to sell at Bethel Farmers’ Market. “We have sort of parallel operations, separate but cooperative,” Dan says. “It works well.” They bought 19 acres of adjoining land with frontage on a paved road, partly to save it from development but also for a farm stand (still in the planning stages) for selling organic meat and vegetables locally. Their policy is not to have big mortgages, but to “pay as we go,” notes Larry. “It’s very much a family-based operation.”

A True Family Farm

“We strive to incorporate the children into the farm work and instill a love of the farm,” Larry continues. Holly homeschools her five children, ages 1 to 8, and farm life is part of their education. They see piglets become hogs and then see them slaughtered for meat. Before slaughter, the family gives thanks and prays so that the children learn exactly where their food comes from, respect for the life of the animal and to let go.

Adopting a new lifestyle has been a big transition, Holly concedes. To live a life rooted in simplicity, they had a lot to learn – to use a wood cook stove, for example. Holly bakes her own bread and avoids most prepared foods. Preparing food fresh from the garden while caring for and schooling the children keeps her busy.

|

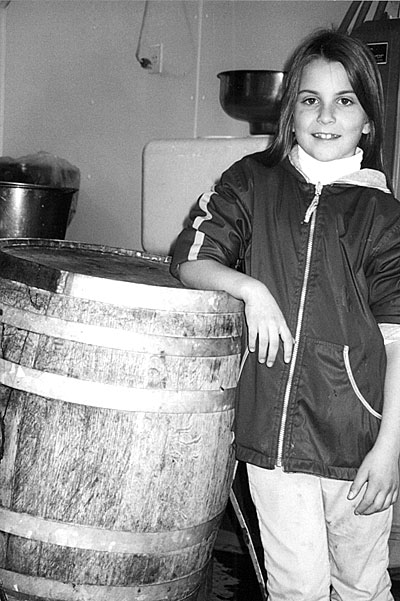

| Laura is the taste-tester for the butter. Joyce White photo. |

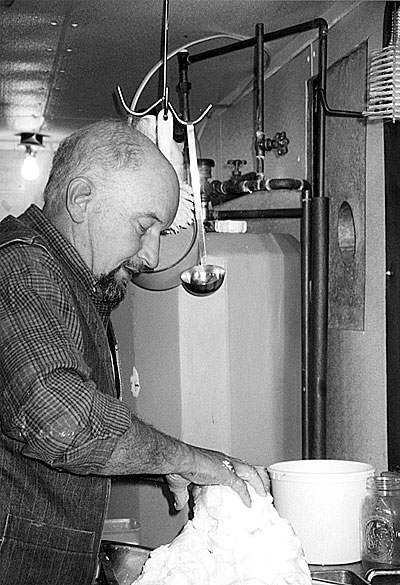

Laura, 8, and Christian, 6, help Grandpa Larry on butter making day. Laura is the official taste tester, Larry says, to be sure he gets the right amount of salt in the 16 pounds of butter they make each week in a big wooden churn. They separate the cream from the milk the old fashioned way, by setting the milk out in pans and skimming off the cream with a slotted skimmer. After scrubbing their hands, the children wrap the butter in special butter paper and put it in a plastic bag. Dan hopes to pass on to their children the experiences and values that his parents gave him.

Organic and Herbal Practices

Complying with the complexities of the organic certification process has been very time consuming, Dan says. “We were so close anyway and it seemed worth it. We wanted the benefit of the label. Now the piglets and calves are born certifiable.” But getting certification for all aspects of their diversified farm was difficult. “You don’t necessarily think of a farmer sitting behind a desk doing research, but I do more studying now than I did in school. And I learned just from being interviewed for MOFGA certification.”

They have 18 organic beef cattle now, plus two milkers, offspring of the original two Jerseys from the Lewiston farm. They rotate the herd from one section of the pasture to the other during the grazing season. The dairy cows had to be certified, because the excess milk is fed to the pigs and because they sell butter. All the gardens are certified, and excess veggies are also fed to the hogs.

Dan raises an heirloom corn (‘Wapsei Valley,’ from Fedco) and plans to plant alfalfa this spring to supplement pricey organic grains. With time, the operation gets easier and more efficient, he adds. “We can add machinery to make things easier. I like tractors and having better machinery. Dad likes horses and wants horse-drawn equipment. We try to live in the best of two worlds.”

Larry and Pat also have two grown daughters – Diane, who is married and lives in Lewiston, and Pauline who lives on the farm. Pauline works as a veterinary technician and Larry describes her as a huge asset. “She’s gardening every minute she’s not away at work.” She’s learning to grow and use herbs to help keep the farm animals and the farm families healthy. She uses Echinacea especially, to boost the immune systems of people and animals, and nettle tea for iron. She’s just a beginner, Pauline emphasizes, mostly self-taught from books; especially helpful have been Herbal Home Remedies by Joyce Wardwell, and Herbal Medicine: The Natural Way to Get Well and Stay Well by Dian Dincin-Buehman.

Pauline helps fill the root cellar with vegetables; they also can carrots and string beans and freeze peas, so the gardens feed both families for much of the year. Pauline also raises goats – an Alpine/Spanish meat goat cross and a Saanen milk goat from which she makes goat cheese. The goats have their separate pasture and shelter. Pauline’s new project will be boarding dogs in an old-fashioned, mortise and tenon building that Dan and Larry are constructing from the farm’s lumber.

|

| Larry Perron begins to work salt into 16 pounds of butter. Joyce White photo. |

As the Perron farm approaches sustainability, Pat says a lot of hard work remains, but things are easier now. The adjustment was especially difficult for her, because, soon after they moved, they realized she needed to go back to work to make ends meet. So, while her teenage children were fitting into a new school community and Larry was involved with the farm, she made the long commute to Lewiston every day for four years – a time when she felt that she belonged neither to the community where she had lived most of her life nor to her new community. “I felt as though I was missing out on my kids’ high school years. I didn’t even fit into the church here or even in my own family for a while.” That changed after she quit her job in Lewiston, began working at the local general store and got to know the local people, joined the Ladies’ Auxiliary for the fire department, and started taking a rug braiding class.

A few years ago, when the family was discussing the need to diversify, Pat said, half jokingly, “We should open a bed and breakfast.” And so the Morrill Farm Bed and Breakfast began. They renovated the woodshed and the shed attic to create three bedrooms with a shared bathroom and sitting room. They provide an old-fashioned farm breakfast of pancakes and sausage or bacon and eggs with toasted, homemade bread.

Living History at Morrill Farm

Their most recent diversification integrates nicely with their beliefs and lifestyle: Morrill Farm provides living history experiences for school and other groups. A neighbor, Debbie Frino, presented the idea of using Morrill Farm to offer living history experiences. She had provided living history programs through Norlands Living History Museum in Livermore for 12 years, taking her inspiration from the creator of those programs, Billie Gammon. Now Frino wanted to focus on Sumner’s town history. The Perrons were reluctant at first, with everything else they had going on, but students’ comments have since convinced them the project is worthwhile. One young man said, “I never cared about history before. Now that I’ve lived it, worked it, tasted it, I can’t wait to get back to my history class.”

|

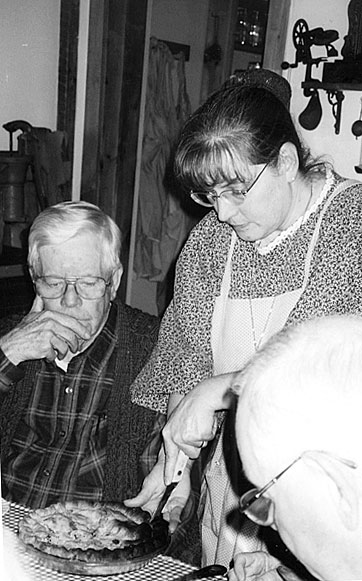

| “Emma” (Debbie Frino) serves apple pie to Sumner Historical Society guests at Morrill Farm. Joyce White photo. |

The Sumner Historical Society sampled Morrill Farm’s living history projects at its November 2004 meeting. People were welcomed into the old-fashioned kitchen by Pat Perron and Debbie Frino, wearing long dresses with aprons, and Larry in zipperless pants and vest. To recreate the period between 1850 and 1880, Larry buys period clothes from an Amish supply catalog (Gohn Brothers) and the women made their dresses. Debbie – known as “Emma” during living history programs – put elastic in her long sleeves to keep them pushed up when she kneads bread or rolls pie crust.

The kitchen is lighted by kerosene lamps with gleaming chimneys, kept that way, Emma says, by washing them every day with hot water and vinegar and by carefully trimming the wicks straight across so that the flame burns steadily and not too high. (This kitchen was created from a garage to replicate a late 19th-century kitchen, but the Perrons have a modern kitchen for everyday use, with a modern gas stove in addition to the lovely old wood cook stove.) People are invited to sit at the long table covered in red and white checked oilcloth, and some sit in rocking chairs around the room. Emma takes two apple pies from the oven of the wood cook stove to serve later. One, a little too brown on the edge, got too close to the firebox, she explains. That Priscilla stove is so old, Emma says, that there’s no temperature gauge, so she adjusts the temperature by leaving the oven door ajar, just as our ancestors did.

Emma explains that they are always in costume when students arrive, and they stay in character and in time period during their entire stay, whether one or several days (although Larry did drop his character with one group that was especially interested in how current, organic methods compare with those from the past). The staff and students portray people who actually lived in Sumner during the 1870s to 1880s, so she is always Emma, and the Perrons portray Robert and Hannah Morrill, grandparents of Alfred Morrill, from whom the Perrons bought the farm. Dan and Holly portray Alfred’s parents, George and Katiebelle. (The farm has been known as the Morrill Farm for so long that the Perrons decided to keep the name.)

|

| Pat uses a cook stove in the recreated kitchen as well as in her everyday kitchen, shown here. Joyce White photo. |

While students are there, every effort is made to replicate 19th-century farm life. Light switches are taped over and they use only wood heat. Exceptions are fire extinguishers, screens on the windows in summer and rolls of toilet paper in the outhouse. Old jokes about corn cobs in the outhouse apparently are based in fact. Debbie’s research into the period indicates that corn was dried on the cob, then shelled during the winter; then those cobs went into a basket in the outhouse to be used as we use toilet paper.

Their first large winter group came from Michigan’s Calvin College in January 2004, during extremely cold weather, and that was challenging. One student commented that when he dropped the toilet paper down the hole, the wind blew it back up. The pipes to the hand pump in the slate sink froze when they had cooking and dishes to do for 27 people. Another group studying 19th century literature at that college came this January, which is not the easiest time for Morrill Farm, but it’s the interim period at the college. They arrive on Friday and are introduced to the program. Meals are planned ahead, and simple but hearty fare is ready for them to cook. Students do everything a farm family would have done – set tables, cook from scratch, wash dishes, and kill, pluck and cook a chicken.

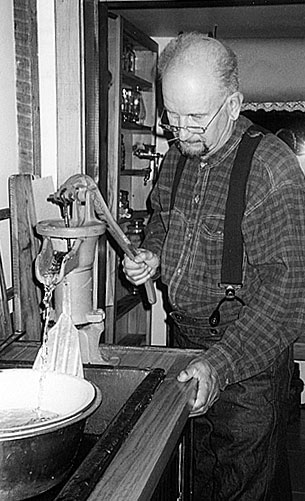

All students experience indoor and outdoor work. Spring jobs may include preparing land for planting, picking rocks, sowing seeds, clearing brush, milking cows and cleaning stalls. In summer, visitors may weed, harvest, build stone walls or make hay. Fall visitors save seed corn, harvest potatoes, cut and stack firewood and make cider. Winter is harder, but students can bring in firewood, split kindling, thresh beans, clean stables, help with milking, skim cream and churn butter. Inside they prepare dry beans for baking, shell corn for planting or popping, prepare and cook vegetables in season, wash dishes with water pumped by hand and heated in large kettles on the wood stove, keep wood fires going, and bake bread or cookies in the wood stove.

All work stops for meals, and everyone sits together at the table with Pa at the head, Ma on his left. Pa serves the main dish – some kind of meat – and the plates get handed down the table. Then Pa gives permission for everyone to take vegetables and bread. Everyone is expected to try at least a small portion of everything. Some college students aren’t accustomed to eating a family-style meal at a table using manners, Emma says; they learn a lot during meals.

|

| Larry Perron pumps water by hand in the 19th-century kitchen that he helped recreate at Morrill Farm. Joyce White photo. |

Each person in the live-in program is given the name of a person who actually lived in Sumner between 1870 and 1885, and is provided with original source research about the town and the people who lived here. Students are asked to learn what they can about their assigned character. They talk about the realities of the time, of life and death. Sumner, for example, had no town farm for elderly or poor people; instead, they stayed in different people’s homes, and that was one way Sumner residents paid taxes.

Larry tells the Sumner Historical Society, “We’ve been preparing for the winter group for months. It takes a lot of organization. We get the whole corn planting done by successive groups of students.” The spring group plants, the summer group hoes and weeds, the fall group harvests, and winter kids shell dried corn and get it ready for planting. Every kid gets a chance to do some spinning on Larry’s wheel, and everyone can try quilting. Last winter’s group started a Calvin College quilt.

The experience is not all work. The Saturday evening dance is the highlight for students, just as it was for our ancestors. Fred Legere comes with the caller to play his harmonica for circle mixers, square dances, contra dances and waltzes. The grandchildren participate along with the whole farm family. Local residents have volunteered in the past to come as a particular historical townsperson dressed in costume.

On Sunday morning, a service is held in the chapel, and Emma notes that the Calvin College choir is great. On Sunday evening, everyone sits around the table and reads and discusses 19th century poetry by lamplight.

“We go to school, too,” Emma points out. “I get to be the school marm. We do penmanship and reading and arithmetic, going through the books. We use slate and slate pencils and ink pens dipped in the ink wells for copying. We stand to read from the readers and even learn a little bit of sewing. Students even have to stand in the corner for misbehavior.” Students are asked to share what they have learned about the residents, which helps them learn more about the history of their adopted town.

Student groups are divided by gender for sleeping, with the smallest number, usually boys, using the B&B guest rooms, and the larger number sleeping in the dormitory-style open chamber over the garage/kitchen, which can sleep seventeen. Students can use chamber pots, emptying them themselves, but Pat says they never do; instead, they use flashlights to visit the outhouse at night.

Arrangements take a lot of time, because all modern furnishings have to be removed from the guest rooms before students arrive and replaced for B&B guests afterwards; and the rooms have to be cleaned, because a lot of dirt gets tracked in both in summer and winter.

The staff at Morrill Farm tailors Living History programs to family gatherings, historical societies, scouts, and other groups, and does day programs as well as live-ins. Morrill Farm can be reached at 207-388-2059; [email protected]; 85 Morrill Road, Sumner, ME 04292.

About the author: Joyce grows herbs, vegetables, berries and flowers in her organic gardens in the western Maine town of Stoneham. While exploring the countryside, she learns about using plant medicine and meets other organic growers whom she learns from and writes about.