By Caleb P. Goossen, Ph.D., MOFGA’s Crop Specialist

Climate impacts are already impacting your garden — whether that’s temperature fluctuations, or periods of drought, or severe or prolonged precipitation. Here I will discuss what impacts have already been observed, and what to expect moving forward. Though I have an interest in matters of weather and climate, I am neither a meteorologist nor a climatologist and can only share my understanding of the most critical components as I understand them — surely, I’ll have left something out! Weather and climate impacts interact with each other, further complicating things. While much of my understanding has been informed by the work of Maine’s state climatologist, Sean Birkel, any errors are more than likely to be my own.

Increased Temperatures

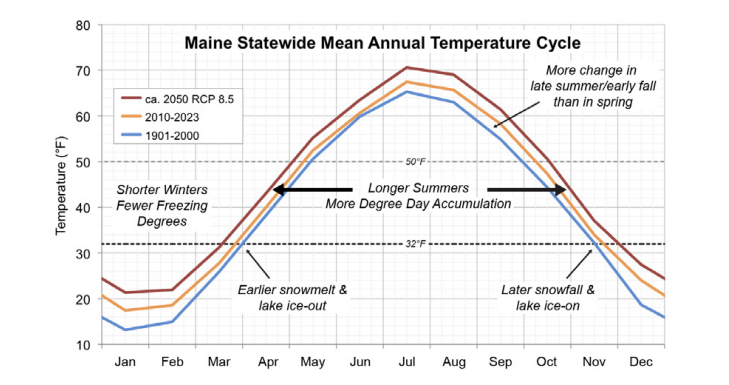

Having grown up calling climate change “global warming,” it feels almost silly to state that one of the most obvious climate impacts that we’re experiencing is increasing temperature. The Northeast’s average annual temperature has increased 3 degrees Fahrenheit since 1895. The simplicity of that statement belies the greater intricacies involved within it. We notice the increased temperature in terms of more warmer-than-normal and fewer cooler-than-normal days in a given year. There are also more daily high temperature records getting set than records for low temperature. However, focusing on this alone overlooks a few important things.

Firstly, maximum daily temperature records are just looking at the top end of the temperature range for any given day. The overnight low temperatures have actually been increasing more than daytime high temperatures. This is associated with increasing humidity — warmer air holds more moisture than colder air, and humid conditions lead to less heat loss overnight than dry conditions.

Secondly, growing degree days should be considered. A growing degree day is a measure of accumulated heat that is well correlated with growth and development of crops and/or pests. Relatively small increases in minimum, maximum, or average daily temperature may not amount to a lot in terms of individual degrees measured at a given moment, but when we consider growing degree day units, we see that relatively small increases in daily temperature minimums and maximums can quickly add up to much higher levels of accumulated heat, allowing for faster growth and development of both crops and pests. There are several different ways to calculate growing degree days, tailoring the calculation to the crop or pest of interest, but the overall idea is that each day’s heat accumulation can be measured as the difference between that day’s average temperature and a minimum development threshold temperature relevant to the species of interest. For example, apple tree flower bud development occurs at temperatures above 43 Fahrenheit. For calculations, 43 F therefore becomes the base temperature. You’ll also need the average temperature, which can be determined by adding the high and low temperatures for the day, and then dividing that value by two. Every degree above the base temperature (i.e., 43 F) on a given day is added to the growing degree days that we use to predict flower bud emergence. With only slightly warmer weather in the late winter and early spring, flower buds may accumulate enough heat to break dormancy and expand, or even fully bloom, earlier in the season. (Unfortunately, these same increased temperatures don’t come with any guarantees that we won’t still receive frosts and killing freezes in the spring, potentially causing major losses to more precociously blooming apple varieties).

Thirdly, while there are warmer temperatures in all seasons throughout the year, the biggest changes are happening at times when we’re not typically thinking of high temperatures — the fall and winter. Though the productive growing season appears to be extending both earlier and later, the most noticeable impact has been milder autumn conditions. Many growers are harvesting far later into the year than previously, and many are pushing their garlic planting date later and later into the year to avoid premature sprouting before the onset of winter conditions. I planted my own garlic in mid-November of 2024; previously, I would have aimed for mid to late October. These warmer late-season conditions have many growers re-working their typical late-season planting dates as well as reconsidering expectations for what can be grown when. However, warmer temperatures are only a piece of the equation for plant growth. Even in warmer autumn conditions, plant growth will eventually be limited, or entirely inhibited, by the shorter daylength of late autumn. At this point in the season, a plant may only be able to produce, via photosynthesis, a similar amount of sugars as it is using to maintain itself without any significant growth.

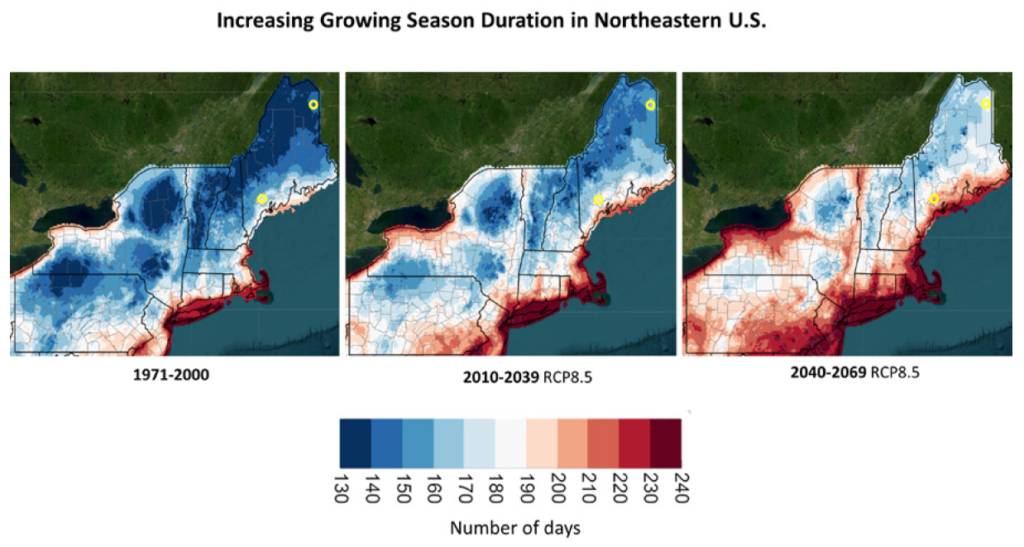

With these three considerations in mind, in the next 30 years the growing season across Maine’s coastal climate division may become more like that of present-day Connecticut, according to climate model projections of the high-emissions warming scenario (RCP 8.5).

Stagnant Weather Patterns and Weather Extremes

Rising temperatures also drive changes in weather patterns, leading to more extremes. Higher temperatures, especially in the oceans, increase water evaporation — intensifying hydrologic cycles and leading to changes in atmospheric circulation. This can lead to us getting stuck in a weather “holding pattern,” as we saw in some of our recent growing seasons that provided either too much or too little rain for too long. It has also increased the likelihood of heavy precipitation.

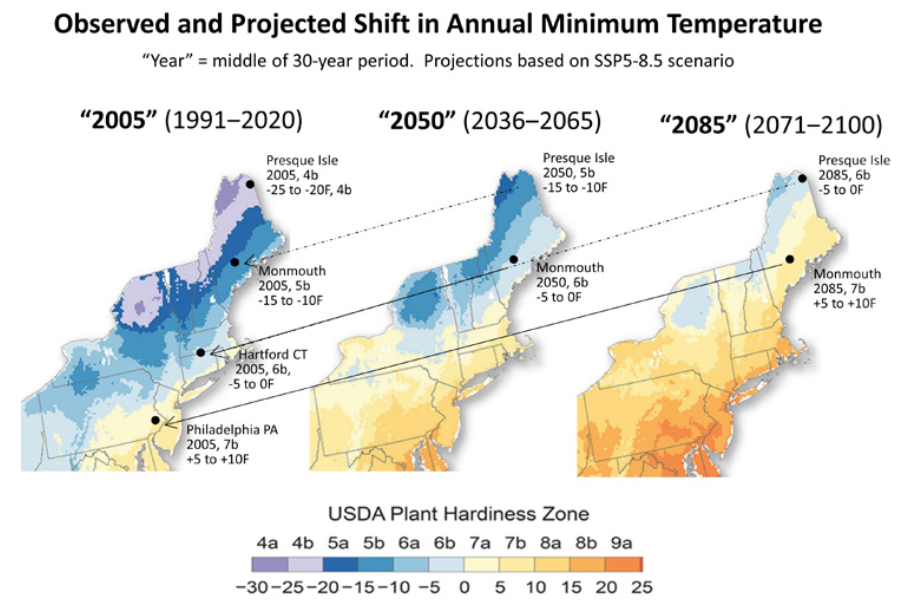

While prolonged dry or wet conditions in the main growing season are probably the most noticeable impacts to growers, the shift from one temperature extreme to the other, which is at times very rapid, can be among the most damaging. “Whipsaw” conditions in the winter or autumn seasons, where extended mild or warm periods swing to very cold temperatures, can cause winter injury to perennial plants that have not achieved sufficient dormancy. The same pattern in the late winter can cause a “false spring” — encouraging perennial plants to break dormancy, at which point their buds may be vulnerable to frost and freeze damage, as we saw in many Maine locations in May of 2023.

With increased global water cycling occurring due to higher temperatures, the Northeast region now receives, on average, about 6 inches more precipitation throughout the year compared to records beginning 1895. Although we still get some abnormally dry years, and have certainly seen some prolonged dry spells with little rain — particularly in the later portions of the growing season — average total annual precipitation is expected to increase an additional 5-14% by the year 2100. Unfortunately, the increase in total precipitation has not been in our ideal scenario of regular gentle rains spaced evenly throughout the year. Instead, the greatest increases in precipitation are happening in the summer months, with heavy rain events — where more than 2 inches of rain fall at a time — becoming increasingly common.

We are already experiencing the growing realities of our changing climate, with more noticeable extremes in temperature, dry spells, and severe or prolonged precipitation. Though we are expected to see more of these, growers of all scales have begun adapting — whether intentionally or not! While the challenges are significant, so too are the opportunities to innovate and grow in harmony with our evolving environment. By staying informed and proactive, we can ensure that our growing practices are resilient and productive.

This article originally appeared in the spring 2025 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.