|

| Nicolas Lindholm and Ruth Fiske of Blue Hill Berry Co. Photo by Kim Kral, courtesy of Blue Hill Berry Co. |

|

| The Blue Hill Berry Co. logo was designed by Molly Blake of Molly B Designs. Photo by Nicolas Lindholm |

|

| Todd Merrill. Photo courtesy of Merrill Blueberry Farms |

|

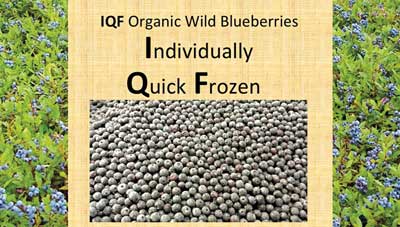

| Merrill Blueberry Farms, now with its third-generation president, Todd Merrill, processed 350,000 pounds from 22 organic growers last year, using the Individually Quick Frozen method. Photo courtesy of Merrill Blueberry Farms |

At MOFGA’s 2017 Farmer to Farmer Conference, Nicolas Lindholm, Todd Merrill and Theresa Gaffney talked about marketing organic blueberries. Gaffney’s information is included in the features about Highland Organics and about online marketing in this issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.

Lindholm, of Blue Hill Berry Company in Penobscot, Maine, said his mentor, Dennis King, told him that anybody can grow a carrot, but the hardest part of farming is selling a carrot.

Blue Hill Berry Company manages 65 to 70 acres of wild blueberry ground, some owned and some leased, most in the Blue Hill area. Lindholm and Ruth Fiske moved to the area in 1996 and started MOFGA-certified organic Hackmatack Farm, growing blueberries and vegetables, and becoming certified in 1997.

“I was trained as a vegetable farmer,” said Lindholm, “going through the MOFGA apprenticeship program in my 20s, working on three large-scale mixed vegetable farms over five years, spending four more years at a seed company.”

Their farm in Penobscot had 5 or 6 acres of tillable land for vegetables and about 15 acres of wild blueberries. “So I came to wild blueberries knowing nothing about the crop but with the experience and knowledge of organic agricultural practices, particularly the importance of the health of the soil – the basis of organic agricultural production. I still use that training as a blueberry farmer today.”

Lindholm’s farming goal has always been to be a small-scale family farmer with an economically viable homestead farm business, producing quality food, caring for a small piece of land and doing the hands-on work himself. He did not want to be a commodity farmer or to be part of the industrial food system; he wanted to provide a living for his family and himself, to provide jobs, and to be part of the rural Maine and organic agricultural community.

He learned that direct sales bring more money for a product and make up for lower-than-average yields of organic wild blueberries. They also build personal relationships with local customers – something “really important to me all along” – and those customers can provide direct feedback.

Telling Your Story

Direct marketing enables Lindholm to be creative – making his own signs, for example. And, most exciting, he gets to educate people, to tell his story. “A huge part of being a successful marketer,” he said, “is having a story and how you tell it.”

One story that Lindholm likes to tell is “the utterly unique aspect of farming wild blueberries. This crop, this species, is in its native homeland here, its center of origin. They don’t really grow anywhere else, and this is where they have the deepest genetic diversity – which is so important, especially for survival of our food crops. This is analogous to being a potato farmer in Peru or apple grower in Kazakhstan.

“Wild blueberries aren’t cultivated; they’re tended. There’s no plowing, no crop rotation, no new varieties from the seed catalog.”

That genetic diversity appears as different foliage in different clones, different flower and berry colors, the way flowers hang on plants, and variations in disease or drought tolerance. Lindholm has one clone that blooms every year but yields little. Frank Drummond, a UMaine entomologist, speculated that that clone may be a super pollen producer. This diversity is integral to Blue Hill Berry Company: “On our farm,” said Lindholm, “we never grade berries by color. It’s important for people to see and taste the breadth and depth of this genetic diversity of our native crop.”

Another story is that “we’re some of the only farmers on earth who use earth, air, water and fire to produce our crop.

“And people are always curious to hear about the organic duff layer, such an important transition zone from air to earth, rich in diversity of life and nutrients, and moisture and air exchange, and chemistry and biology and physics …”

Everyone wants to hear about bees, he added, and about the difference between native pollinators and honeybees.

The two-year cycle of wild blueberries is also interesting, starting with burning, then going through an icy winter and coming out with abundant crops.

“People always want to know how awful, hard, romantic harvesting is,” Lindholm continued; “what the rake looks like. I bring a rake to market with me. People want to know the history of it, how it’s used.”

Saving Land and Building Markets

Preserving land – including farmland – is also important to Lindholm, especially given the development pressure in the Blue Hill area. “If we turned all our blueberry fields into house lots, we’d lose the tourism and the food produced,” he noted.

Lindholm built his markets – almost 100 percent fresh-pack – slowly and steadily. He sold his first berries in 1998, raking about 2,000 pounds from 2 or 3 acres each summer. By 2010 the harvest was about 10 acres per year, yielding 8,000 to 10,000 pounds. His average yield, with low organic management, has been about 1,000 pounds per acre. As of 2016 he’s been harvesting about 30 acres per year and in 2017 got almost 32,000 pounds of “high value, highly clean berries” – not field weight. About 10 to 15 percent is lost in sorting the fresh-pack line.

For the first few years he sold pints and quarts at local farmers’ markets. By 1999 he had added 10-pound boxes, and demand was building as people realized blueberries were easy to use and freeze. By 2004 they were selling a lot of pre-ordered 10-pound boxes as well as pints and quarts. By 2005 the larger sizes and bulk sales had expanded outside the farmers’ market, and Blue Hill started doing a few group orders. By 2010 Lindholm focused on expanding the blueberry company. He wrote a business plan, got funding from the Farm Service Agency and incorporated the blueberry company separate from the vegetable farm – to separate their personal assets from the farm business, to leverage more funding for the blueberry business and to create more marketing opportunities for the berries. They leased more land, sold outside Hancock County and started marketing with other large farms – mostly vegetable CSAs all over Maine.

“I’ve been a vegetable farmer and been involved with MOFGA, so I knew a lot of the vegetable farmers,” said Lindholm. “I built relationships with them, selling our blueberries, usually in a one-day, local event to their CSA customers. We developed other groups orders, such as the MOFGA office [staff]. In 2012 I got into the Portland Farmers’ Market, where we really built bulk demand. We showed up there with pints and quarts at first, and people said ‘I don’t know if we can eat all of those.’ By last summer we found that 5-pound boxes flew off the table.” In winter he now does three bulk deliveries to Portland.

They also started a pre-buy CSA about five years ago. Customers pay a fixed price in April or May when pollinators are rented, and they get a guaranteed amount of blueberries in early August.

Fresh frozen blueberries are a new product. “We take our grade A blueberries off our fresh-pack line, pack them in 10- or 30-pound boxes and put them right into the freezer, unwashed so that they still have the bloom on them. We then package them into other sizes – 1 quart, 1-1/2 quart, 3 quarts and a 5-pound bag. These frozen berries as of 2016 were 15 to 20 percent of our sales. Fresh-pack was 80 to 85 percent.” Most of the frozen berries are sold directly, although some stores buy them.

In 2016 Lindholm launched a website and started shipping frozen blueberries throughout the continental United States, with dry ice in an insulated box, using FedEx second-day shipping. Only one or two of about 200 shipments have been delayed by storms. FedEx reimbursed him for the lost product.

Lindholm said at least 50 percent of his time goes into dealing with customers, “but that’s what I wanted to do.”

Nutrition-driven Markets

He’s noticed a couple of major marketing trends over the past five or so years: People are not making pies, muffins or pancakes with their blueberries so often but are making smoothies, driven by nutritional research on the health benefits of blueberries. “It’s been a real change for our culture to look at food as medicine,” said Lindholm.

Anthony William, author of “The Medical Medium” and “Life Changing Foods,” touts eating fresh produce, with Maine wild blueberries (organic if possible) at the top of his list. “He’s driving a huge percentage of sales,” said Lindholm.

Lindholm prefers to label his products with the MOFGA Certified Organic sticker; he doesn’t like the design of the USDA organic sticker.

He has sold to chefs in the past, but they don’t buy in the volume he wants to offer.

Asked about the term “wild,” a Farmer to Farmer participant said the USDA defines blueberries as either wild or tame (cultivated). Customers often ask Lindholm, “If the berries are wild, then aren’t they organic?”

“The term wild,” said Lindholm, “is somewhat of a misnomer. They are actually very tended crops. They aren’t just wild out there in the woods. And nonorganic ‘wild’ blueberry growers are very much managing these crops intentionally.”

Steady Growth for Organic at Merrill Blueberry Farms

Todd Merrill, president of Merrill Blueberry Farms in Hancock, said his grandfather started the business in 1925. His father and uncle took over when his grandfather died. In 2007 they told Merrill they were either going to sell the business, hire management from outside the company or hire him.

“So I moved my family to where I grew up, in Ellsworth, and started as general manager and worked my way up to president over four years.” His nephew will work there after he graduates from UMaine.

The company started in a smaller facility on Main Street in Ellsworth, selling about 1 million to 2 million pounds, then built a new facility in Hancock in 1980 to handle 4 or 5 million pounds. Now its 10 fulltime employees handle 4 to 8 million pounds of IQF (individually quick frozen) berries, selling 30-pound and 10-pound boxes wholesale and to walk-in customers from the public. The berries come in fresh, full of leaves, twigs, etc., and the equipment removes the debris as well as lighter and green berries and rocks. The remaining berries are frozen in IQF tunnels, coming out at -20 F. Then they go through a couple of barrel rolls to remove any stems. After that a laser sorter sorts them by color, shape and size, and then 24 people at a pick-over table remove anything that doesn’t look good.

In 2009 Merrill processed its first organic wild blueberries from a field managed by Dwayne Shaw of Downeast Salmon Federation for Maine Heritage Trust.

“I had customers who were asking for organic,” said Merrill. “I went through the steps with MOFGA to certify our facility, wrote an organic handling plan, followed other steps – made sure no conventional berries ran on the same truck as organic berries, created different colored tags for inside our plant telling us what day they were harvested. We don’t want to get more than a day behind in processing. We came up with a green tag for the organic berries. We have to segregate them every step of the way. We have to defrost our system every 16 hours and sanitize it. Then whatever organic berries have come in, I run through the clean system first.

“In 2009 we harvested that field in two or three days and brought in 65,000 pounds from the one field from Dwayne.” Others brought organic berries, for a total of 82,000 pounds. In 2017 Merrill processed 350,000 pounds from 22 organic growers. That could have been half a million pounds, if not for the drought, said Merrill. Most of those organic growers use walk-behind machines, so their berries include small and cull berries, sticks and stems – “weight I pay for that’s lost,” said Merrill. So his 2017 packed product weighed closer to 300,000 pounds.

Merrill sells to food brokers, many of whom repack the 30-pound boxes into 15-ounce, 1-pound and 5-pound bags and sell them in grocery stores throughout the country. Some make muffins, jams, pie fillings, smoothies or toppings.

“I don’t have a big distributor,” he said, “which would be nice because they will get them directly to restaurants. Those would be nice to work into.”

About 60,000 of the 300,000 pounds of organic berries are bought back by the farmers who brought them in. “If they bring in 10,000 pounds of fresh wild blueberries, I allow them to buy back 85 percent of what they bring to me – 8,500 pounds – because of my losses. The grower doesn’t necessarily get his or her own berries back.” The buyback price in late 2017 for cleaned, frozen berries in 30-pound boxes was 89 cents per pound. If a grower could bring in about 20,000 pounds at once, Merrill could process them separately.

Merrill believes that the organic wild blueberry industry is in its infancy and has a lot of growth potential. “I can’t supply everyone who asks me for IQF organic wild blueberries. The demand seems to have increased recently, in the United States and in Europe and Asia.

Merrill has had inquiries for drying berries and said that many Asian countries prefer dried, which he doesn’t supply, “but I can sell my IQF berries to others to dry.” He would like to add drying to the company’s capabilities, but it would require developing a market.

The recent low price of conventional berries has been a big incentive for growers to transition to organic, he said.

Merrill plans by 2019 to have close to 1 million pounds or more of organic berries annually. That’s only 1 percent of the Maine crop, “so there’s a lot of room to grow,” he said.

He has paid $1.40 to $1.60 per pound for fresh organic berries delivered to the plant over the last six years. The price for conventional was 27 cents per pound in 2016, and the high over the past six years was 70 cents.

In Waldo, Knox and Hancock counties, where soils are rougher and rockier than in Washington County, conventional growers are lucky to get 5,000 pounds per acre and commonly average 3,000 to 4,000 pounds under good conditions. If organic berries yielded 2,500 to 3,000 pounds per acre at $1.40 to $1.60 compared to 27 to 50 cents for conventional, “the math adds up,” said Merrill.

The competition is cultivated organic blueberries, and wild organic blueberries from Canada. Yields in Quebec have ranged from 14 million of 125 million pounds in the last few years, partly because of early frosts there. “Buyers want a consistent supply, not this variation,” said Merrill.

Merrill pays for trucking. For a grower in Brunswick, the company paid an additional 4 or 5 cents per pound to transport the berries to Hancock.