|

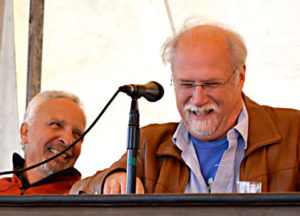

| Don Hoenig, V.M.D., (far left) said, “This idea that there is rampant resistant bacteria moving from livestock and poultry into the human population and resulting in treatment failures and disease in the human population is just not true.” He is optimistic about FDA’s voluntary guidelines regarding antibiotic use in livestock. Photos by Jean English. |

2014 Common Ground Country Fair Teach-In

How do antibiotic-resistant bacteria affect our health and the health of livestock? What can we do about this growing problem? These issues were discussed at a teach-in at the 2014 Common Ground Country Fair by Stephen Sears, M.D, M.P.H., chief of staff at VA Maine Healthcare System (Togus); Don Hoenig, V.M.D., retired state veterinarian, now with UMaine Cooperative Extension and the American Humane Association; Jennifer Obadia, Ph.D., New England coordinator for the Healthy Food in Health Care Program of the global coalition Health Care Without Harm (HCWH); and MOFGA certified organic farmer Alice Percy of Treble Ridge Farm in Whitefield. Nancy Ross, Ph.D., of MOFGA’s Public Policy Committee, moderated the session.

Dr. Hoenig defined an antibiotic as a chemical substance produced by a microorganism (and produced synthetically as well) that can inhibit the growth of or kill other microorganisms.

Antibiotics are used in farm animals generally to treat bacterial infections, Hoenig continued. They do not fight viruses such as the common cold in people or the flu.

For animal use, antibiotics can be obtained over-the-counter (without a prescription, e.g., at farm supply stores), by prescription from a veterinarian, or through a “veterinary feed directive” (the antibiotic is in the feed; this also requires a veterinarian’s involvement).

Antibiotics are used in animals to treat a disease (such as pneumonia or a skin infection caused by a bacterium); to prevent a disease (such as diarrhea in baby chicks or mastitis in dairy cows) or to control a disease (such as “shipping fever” in a group of cattle to be transported a long distance). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies treatment, control and prevention as “therapeutic” uses.

The FDA also permits non-therapeutic or “production use” of antibiotics in livestock and poultry. Antibiotics used in this manner are approved for growth promotion and/or feed efficiency. Non-therapeutic use is most common in chickens raised for meat (broilers), turkeys, swine and on some beef feedlots. The exact mechanism is not understood, but some of these antibiotics are thought to boost animal growth by eliminating some harmful gut bacteria.

Since 1993, all antibiotics approved for use in food-producing animals have required a prescription or veterinary feed directive.

Maine farmers, said Hoenig, are not heavily involved in broiler, turkey or swine production or in raising feedlot beef, so their use of non-therapeutic antibiotics is extremely low or non-existent. Even the big laying hen complexes in central Maine do not use non-therapeutic antibiotics.

Antibiotic Resistance

Any time an antibiotic is used, said Hoenig, a few resistant bacteria survive. Due to criticism of agricultural uses of antibiotics as contributing to this resistance, the FDA in December 2013 issued new voluntary guidelines with two significant changes regarding non-therapeutic antibiotic use. This action is focused on medically important antibiotics, i.e., those used to treat human disease.

First, the FDA now considers non-therapeutic use of antibiotics in feed or water to be injudicious, and it will phase out approval for all non-therapeutic uses within three years from December 2013. All 26 drug manufacturers have agreed to comply with this new policy. Companies will either withdraw some drugs from the market or will apply for new approvals for therapeutic uses.

Second, the FDA will now require veterinary oversight of all antibiotics and will draft new guidelines for this oversight. Most likely, it will use the veterinary feed directive route for farmers to obtain them.

Avoiding Antibiotic Residues in Food

Three government agencies track resistance trends in people, animals and food, said Hoenig. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracks samples from human labs, USDA samples animals and the FDA monitors retail meats.

Also, as a provision of their license to practice, veterinarians must follow judicious use principles when using or prescribing antibiotics. Those principles include proper storage and disposal of outdated drugs; correct administration of antibiotics, i.e., orally, subcutaneously, etc.; proper dosages; required withholding times from meat and milk; and advising farmers on correct procedures for antibiotic use.

According to the CDC, Hoenig continued, 2 million people acquire serious infections with resistant bacteria, and 23,000 die each year of antibiotic-resistant infections. Fifty percent of antibiotics prescribed to people are not needed.

In written comments, Hoenig said that the 80 percent figure that consumer groups often cite for the percent of antibiotics used in agriculture is misleading, as it reflects total kilograms sold by the manufacturer and not the volume sold to the end user (farmer). The CDC does say, “It is difficult to compare the amount of drugs used in food animals with the amount used in humans but there is evidence that more antibiotics are used on food production.” (CDC report, Antibiotic Resistance Trends in the U.S. 2013.)

Several scientific, peer-reviewed risk assessments demonstrate that resistance in animals does not transfer to humans in measurable amounts, if at all, said Hoenig. Still, chicken producers are phasing out subtherapeutic or “growth uses” of antibiotics that are important in treating humans.

Hoenig stressed that antibiotic resistance is a characteristic of bacteria, not of chickens or people; what can transfer between people and animals are antibiotic-resistant bacteria, not antibiotic resistance. “Antibiotic resistance is a universal phenomenon in bacteria,” said Hoenig. “To say that an antibiotic resistant strain of bacteria was isolated from a person or flock is almost meaningless. Rather, it is normal, regardless of antibiotic use.”

Hoenig related that in June 2006 Maine adopted a purchasing policy relating to antibiotic use:

“In soliciting bids for meat products, the Division of Purchases shall inform meat suppliers that, assuming similarity in quality, quantity, availability and price, the State prefers to purchase products that have not been produced using medically important antibiotics for non-therapeutic purposes. The Division of Purchases shall continue to encourage school districts to take advantage of contracts awarded to suppliers whose products meet this preference.”

However, the Maine purchasing director reports that the current Maine policy has a limited reach: “. . .the State’s primary ‘end users’ of the contract being at the Department of Corrections and the State’s Riverview and Dorothea Dix Psychiatric Centers. (School districts can use the contract, but generally do not choose to, and make their own arrangements.)”

|

| Stephen Sears, M.D, M.P.H., sees antibiotic resistance as “one of the biggest public health threats of our time.” |

The Human Aspects of Antibiotic Resistance

“Antibiotic resistance is considered to be one of the biggest public health threats of our time,” said Dr. Sears. “We are losing the battle with bacteria. In humans, there are more and more bacteria that we can treat less and less well than we could a few years ago.

“Every time you take or are exposed to an antibiotic, you have the potential of developing antibiotic-resistant bacteria within you or on you.”

Sears said that within five years of development of penicillin, resistance evolved. So we made new antibiotics, which led to more resistance, which led to new antibiotics and more resistance, etc.

“The strategy of finding a new antibiotic is no longer viable. We’ve basically found or created all we could. We are losing the battle because we’ve been making antibiotics for 90 years; bacteria have been around for 3.4 billion years.”

When you get treated with an antibiotic, it kills some but not all of the bacteria. Some replicate and develop resistance to that antibiotic. Within 8 hours, more than 100 million bacteria can grow from a single bacterium, because of binary fission (one divides into two, which divide into four, which divide into eight …). Exposed to low levels of antibiotics, some of those bacteria continue to replicate because they don’t die.

“That’s what’s so concerning about using antibiotics en masse in … people or animals. It’s how to produce resistance.”

So now we have MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), gram-negative rods (E. coli), VREs (vancomycin-resistant Enterococci – the new superbug that is resistant to everything, worldwide) and other resistant organisms.

Ramifications

The U.S. population, Sears continued, experiences about 76 million foodborne illnesses yearly, with about 25,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths. So one in four Americans gets sick each year with a foodborne illness. One in 1,000 will be hospitalized. The cost is about $65 billion. The causes are Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli O157, Campylobacter – all bacteria found in animals and in our food supply.

“So we now have foodborne illness with resistant bacteria,” said Sears. “The Salmonellas are now resistant, as are some of the E. colis.”

MRSA is now found in pigs, cats, dogs and people. “We can find clearly documented situations where we have had a pig give it to a human, who then got an infection, and we can see it going both ways,” said Sears.

|

| One goal of Healthy Food in Health Care, said Jennifer Obadia, Ph.D., “is to eliminate the use of antibiotics in animal agriculture for non-therapeutic purposes.” |

Eliminate Non-therapeutic Antibiotic Use

Jennifer Obadia said that Health Care without Harm – the international organization that works with the health care sector on environmental health issues – has a U.S. program called Healthy Food in Health Care, which is working with institutions to increase purchasing of sustainably raised, nutritious food. Its main focus now is on antibiotic resistance.

“Our goal as an organization is to eliminate the use of antibiotics in animal agriculture for non-therapeutic purposes,” said Obadia. “The CDC, the Institute of Medicine, the World Health Organization and a host of organizations say this is a critical step if we’re going to preserve the use of antibiotics for human health. The reason for the focus on animal use is because 80 percent of antibiotics by sales are for the agricultural sector. About 15 percent is for human therapy. The remainder are in miscellaneous things, like antibacterial soaps.”

Obadia praised FDA’s new guidance saying that antibiotics should not be used for non-therapeutic purposes, although “the language is a little vague.”

Institutions and corporations are making changes, Obadia continued. Perdue says it won’t use antibiotics in its hatcheries. To further encourage this trend, she said, buy meat that has been raised without non-therapeutic use of antibiotics.

“If something is certified organic, it hasn’t had any antibiotics. In an organic system, if you have to treat an animal with antibiotics because it’s sick, it has to be taken out of organic certification. Know your farmer. If they are using antibiotics routinely for growth promoting, tell them that you care. Talk to the person at your supermarket who orders meat, and ask them to carry meat raised without antibiotics. Talk to your policy makers” and food service directors.

|

| Maine organic farmer Alice Percy said that relying on antibiotics to routinely prevent illness “is a symptom of the American expectation for cheap food.” |

A Farmer’s View

Since 2005, Alice and Rufus Percy have been raising organic pork, hay and grain. They keep four to six sows and raise 50 to 80 pigs every year.

In 2005, they were one of four organic pork producers in Maine. The figure is about the same now.

“A lot of people don’t really have a concept of what ‘organic’ means when it comes to livestock,” said Percy. “I often get asked at farmers’ markets, ‘Organic pork – Does that mean that you don’t spray your pigs with pesticides?’ And I say, ‘Well, I don’t … and that’s just the beginning.’

“I think spraying things with pesticides is often how people approach the concept of organic agriculture,” said Percy, but “the basic concept is that if you have a healthy system, then you will have a healthy crop, and a healthy crop does not require crutches like pesticides or synthetic medication … the same is true for our livestock. We can’t just feed organic grain and withhold synthetic medications and end up with healthy animals that will produce a crop of pork. So we rely on low stocking densities, quality feed with carefully calculated nutrition, an opportunity for our animals to express their natural behaviors. Our animals are out on pasture in the summer, and when they’re in the barns in winter, they have outdoor access – and hay bedding that they can root in. These things help make our animals resilient and have strong immune systems so that we can largely avoid those synthetic medications that are prohibited in organic agriculture.”

When an animal does become sick in an organic system, Percy continued, “you can’t let it suffer to keep it organic. So when I use an antibiotic, I have to find an alternate market for those animals; I can no longer claim that those animals are organic.”

Treble Ridge Farm also participates in the Animal Welfare Approved program, which also expects that farmers maintain a healthy system for animals and do not routinely use synthetic medication. “In their system if an animal becomes sick and you can document that the use of antibiotics was warranted, they require you to wait twice the labeled withdrawal time before the animal can go to slaughter and can still be sold under its label.”

Percy said that relying on antibiotics to routinely prevent illness “is a symptom of the American expectation for cheap food, because if you go to antibiotics first to prevent a disease problem instead of first going to cultural controls, such as keeping a clean environment, and a lower stocking density, and lowering stress, and keeping nutrition at the top of the line – going to medications first is the cheap way to do it.” Packing more animals into a small building is cheaper than having enough land and fencing to pasture them. Conventional farmers can use sheep byproducts for animal feed, can use antibiotics, and then can sell cheap pork, chicken and feedlot beef.

The increased barn space and time to feed the animals that are spread out on pasture adds costs, said Percy.

She added, “When you choose to buy organic food (or farm organically), you probably are lowering your exposure to harmful residues (e.g., of pesticides). You are not eliminating them. You are choosing a better system and voting for the system that you would like to see in the world. If everybody adopted those systems, then we would live in a much purer world.

“Voting with your wallet is very important but it may cost a lot more than conventional. I don’t have an instant solution for that … It’s something MOFGA’s helping us work toward; all the farmers are putting their heads together.”

Obadia said Health Care without Harm advocates “the balanced menu approach” – that people evaluate their overall diet. “One thing Americans are not deficient in is protein. We eat more than our fair share. So perhaps have one serving less of meat per week, and have that be a quality option.”

Percy agreed. “Eat less meat and make it good meat.”

Animals to Humans?

Asked about the human health effects of antibiotics that are used on animals but not on humans, Sears said most antibiotics used in animals may not be used in humans but are related. “There are only so many ways that bacteria can become resistant. So resistance genes often are passed from bacteria to bacteria … As you create increasing resistance, the potential for those genes to pick up other resistance grows … I think there are theoretical arguments that it is short-sighted to think that because a class of antibiotics is not used in humans, it won’t cause resistance.”

Hoenig said FDA’s Guidance for Industry #152 lists medically important antibiotics. “There are antibiotics used on animals that are not on that list, so they’re not considered to be medically important – like coccidiostats in poultry” and “ionophores used in cattle and poultry. Can they generate resistance in animals? Possibly, but they’re not used in humans.

“This idea that there is rampant resistant bacteria moving from livestock and poultry into the human population and resulting in treatment failures and disease in the human population is just not true,” said Hoenig. “There are very small numbers of documented cases where that has happened.” Still, he supports limiting antibiotic use in livestock and poultry.

Sears said, “My biggest concern is that we’re seeing an incredible shift in resistance across the planet. So it’s animals and humans overall.”

Obadia noted studies in North Carolina showing large numbers of antibiotic-resistant bacteria on farmworkers’ bodies as a result of daily exposure to manure lagoons and the farm environment. “They’re a population at risk for a lot of ailments and not as well protected … as other workers are.”

“The data from North Carolina about farmworkers with MRSA on their skin is compelling,” said Hoenig, “but are there treatment failures because of that? No. Is there a lot of disease because of that? Not to my knowledge.”

Wash Your Hands

Asked about hand cleaners, Sears said hand sanitizers are alcohol-based gels – antiseptics, not antibiotics. The best thing you can do, he said, is wash your hands before you eat.

Hoenig – “a firm believer that you have to eat a peck of dirt” (to gain immunity) – also advised washing hands before eating, but “I think we have gone overboard with disinfectants, hand sanitizers. I don’t have data to back that up, but soap and warm water is great.”

Sharon Tisher, a member of MOFGA’s Public Policy Committee, noted the difference between sanitizers and antibacterial soaps, cosmetics and toothpastes. She said the FDA has just asked companies that advertise antibacterial soaps to prove that they’re beneficial. She said research to date shows that regular soap is as good as antibacterial, and the widely used antibacterial triclosan has some toxicity issues.

Sears said, “In the hospital environment, which is where we have the most problem transmitting bacteria, the only things we recommend are alcohol-based gels or hand washing, and we actually recommend hand washing first.”

Voluntary Guidelines Effective?

Nancy Ross asked about potential pitfalls of FDA’s voluntary guidelines regarding antibiotic use with livestock.

Hoenig said the two steps FDA is taking are big, and he is optimistic.

Obadia said she is optimistic but slightly skeptical. “What systems get put in place for tracking and transparency are important – what materials [are used] on what animals, quantities … I would lean more toward making it mandatory instead of voluntary, because bacteria can evolve so quickly that we want to be operating more from a precautionary principle.”

Hoenig said the Danes had been using tremendous quantities of non-therapeutic antibiotics before they were banned in 2000. Antibiotic use in livestock dropped precipitously at first, but then therapeutic use increased as farmers tried to figure out how to adapt. “More animals got sick, more animals died,” said Hoenig. Colleagues who have been to Denmark have told him data on the effectiveness of the ban are not black and white.

Sears said Denmark also put strong controls on human use of antibiotics at the same time. Now rates of antibiotic-resistant staph are 5-10 percent in Denmark and 40 to 60 percent in the United States.

Percy said a lot of government regulation handed down to farmers has not been scale-appropriate, and banning antibiotics would be another instance of that.

Antibiotic resistance exists because of inappropriate use of these medicines in humans and on industrial farms, said Percy. The latter “have veterinarians on their staff, and they’re a lot more likely to get antibiotics whenever they want them, in my opinion. I do not have a veterinarian on my staff. Don [Hoenig] has been extraordinarily helpful. Expert use of a veterinarian is crucial when you need it. In the case of a small farmer, it can also often be very expensive. I’ve been farming for 10 years. I know what a case of acute Erysipelas looks like, and I know I need to get penicillin into that animal or it’s going to die soon. I would feel resentful if I had to incur a $200 vet bill before I could treat that animal. If you’ve got mandatory veterinary oversight before somebody can use an antibiotic for therapeutic purposes, I don’t think that solves the situation if the big guys can still get antibiotics whenever they want them.”

Hoenig said FDA’s new policy will apply only to non-therapeutic use. “You can get a lot of antibiotics over the counter. You can still get penicillin. Also, I wish we had a policy for organic like we used to have (before the National Organic Standards) that allowed a double withholding time.” Then an organic producer could treat an animal with acute Erysipelas with penicillin, which would be out of the animal’s system by the time it was sold. Now, though, a treated animal “is out of the organic system forever, even if it’s a 16-week-old pig, even if it’s a breeder.”

It’s Complicated

About this complicated topic, Hoenig quoted a colleague: “If you think you understand antimicrobial resistance, then it has not been properly explained to you.”

Recent Reports

In an annual report released in September 2014, the FDA said the amount of medically important antibiotics sold to farmers and ranchers for use in animals raised for meat grew by 16 percent from 2009 to 2012. Sales of cephalosporins – important in human health – rose by 8 percent in 2012 and by 37 percent from 2009 to 2012.

The report detailed (for the first time in some cases) how the antibiotics were used. About 70 percent were sold as animal feed additives and about 22 percent as drinking water additives. About 97 percent were sold over the counter without a prescription. (“Antibiotics in Livestock: F.D.A. Finds Use Is Rising,” by Sabrina Tavernise The New York Times, Oct. 2, 2014; www.nytimes.com/2014/10/03/science/antibiotics-in-livestock-fda-finds-use-is-rising.html?_r=0; “2012 Summary Report on Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals,” FDA, Sept. 2014; www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/AnimalDrugUserFeeActADUFA/UCM416983.pdf)

Reuters reports that, based on internal records (“feed tickets”) it examined relating to Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Perdue Farms, George’s and Koch Foods, major U.S. poultry firms are administering antibiotics to their flocks routinely (not just when birds are sick), far more pervasively than regulators realize, and at low doses that can promote development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, posing a potential risk to human health. Reuters found that antibiotic use by these companies sometimes differed from statements about their use on companies’ websites. (“Farmaceuticals,” by Brian Grow, P. J. Huffsutter and Michael Erman, Reuters, Sept. 15, 2014; www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/farmaceuticals-the-drugs-fed-to-farm-animals-and-the-risks-posed-to-humans/)

Ten of 22 workers at industrial hog farms in North Carolina were tested for the antibiotic-resistant bacterium Staphylococcus aureus and were found to carry strains in their noses for up to four days. Six other workers carried the antibiotic-resistant strains intermittently, and three carried S. aureus strains that were not resistant to antibiotics. The 86 percent of workers carrying S. aureus was about one-third higher than the rate in the general population. (“Taking a Health Hazard Home,” by Stephanie Strom, The New York Times, Set. 15, 2014; www.nytimes.com/2014/09/16/science/study-finds-pork-workers-retain-bacteria-for-days.html?_r=0; Original study: Persistence of livestock-associated antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among industrial hog operation workers in North Carolina over 14 days, by Maya Nadimpalli et al., Occupational & Environmental Medicine, Sept. 8, 2014; https://oem.bmj.com/content/early/2014/09/05/oemed-2014-102095)