|

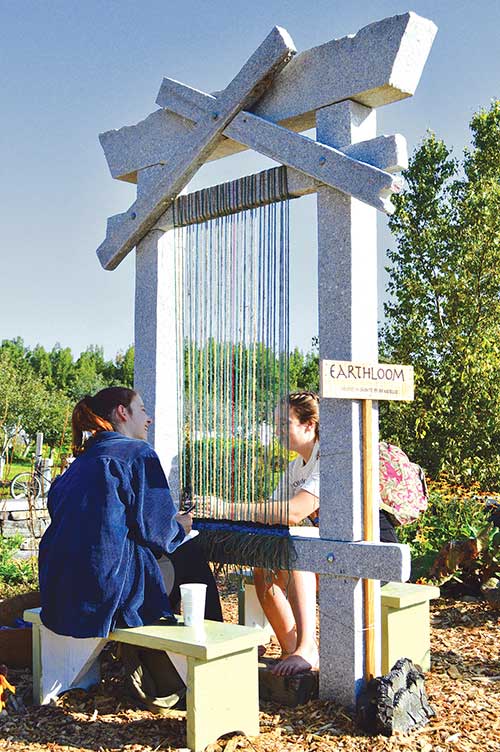

| Susan Barrett Merrill’s husband, Richard, made the old cedar EarthLoom that stood in the pocket park and dye garden at MOFGA’s Common Ground Education Center for many years. English photo |

|

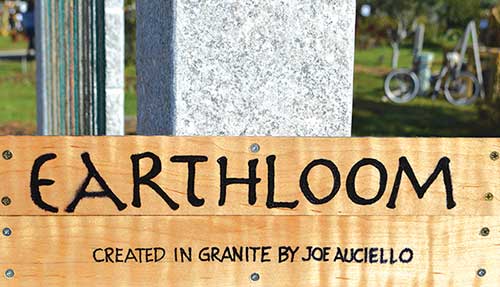

| The new granite EarthLoom. English photo |

|

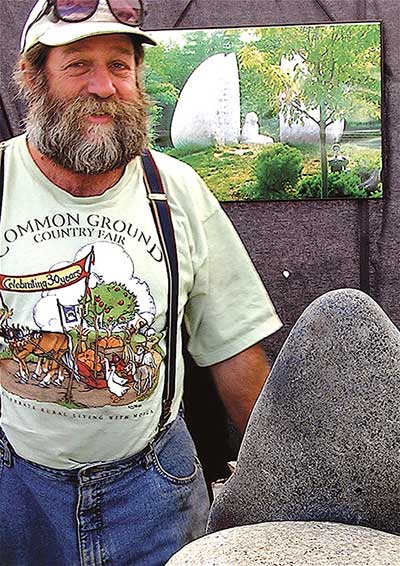

| Joe Auciello of the Maine Stoneworkers Guild created the new EarthLoom. |

|

|

| Merrill designed the EarthLoom and makes Zati masks from fiber woven on a loom. “Zati” is an Urdu word meaning “from the inside” or “the spirit inside.” English photo |

|

| In addition to the full-sized EarthLoom, a portable version called a Journey Loom keeps kids of all ages busy at the Common Ground Country Fair. English photo |

By Sonja Heyck-Merlin

Early each morning since the 2005 debut of an EarthLoom at the Common Ground Country Fair, Wednesday Spinner and Weaving a Life founder Susan Merrill spends an hour and a half preparing the loom for weaving.

Located across a busy walking lane from the Wednesday Spinners’ tent, the 9 x 4 ½-foot-tall EarthLoom is the focal point of the “pocket park” where the spinners’ dye garden and a bench-height stone wall surround the loom. Comprised of seven pieces, the large vertical rectangular frame has diagonal bracing near the top. People tell Merrill that the architecture of the loom reminds them of a Buddhist temple or a krusha, an ancient Siberian symbol of home.

EarthLooms, like the one at Common Ground, exist around the world: in playgrounds, libraries, national parks, retirement communities and museums. You can find them at funerals, retreats, weddings and graduations. No matter the venue, the goal of weaving on an EarthLoom remains consistent. “The EarthLoom,” Merrill says, “is a living symbol, planted in the ground, of our intention to weave together the fabric of community.”

Also called a GardenLoom, the EarthLoom is one of four sizes of looms that Weaving a Life sells, with all four versions having the unique seven-piece structure. The design originates from Merrill’s childhood meanderings on the Maine coast, weaving together seaweeds, sticks and other natural materials. Whether weaving on one her lap-sized models or using a larger model, she sees the process “as a way to explore the inner self and create balance and wholeness in your life and ways to work in the world with peace of mind.”

The New Granite EarthLoom

The third iteration of the EarthLoom was unveiled at the 2019 Common Ground Country Fair. The beautiful granite sculpture replaced the second wooden version. Merrill and Joe Auciello, a member of the Maine Stone Workers Guild, whose presentation area at the Fair abuts the Wednesday Spinners’, conceived the idea of the stone loom together.

Merrill recounts, “I was sitting on the wall during the Fair, and Joe came and sat beside me. I expressed that it was a shame that our loom was starting to rot. He said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to make one out of stone?’”

The loom sculpture adds to the presence of the Maine Stone Workers Guild etched throughout the fairgrounds: the sundial in the common, the north gate arch and numerous benches.

From conception to installation, the granite loom took three years to complete, supported by an $800 grant from the Maine Arts Commission. Using Merrill’s design, Auciello, with help from guild members Ray Carbone and Norman Casas, cut the seven pieces out of two large stones donated by JC Stone in Jefferson, Maine. Some parts, says Auciello, “were split and cut as a demonstration at the Fair.”

At the site the seven pieces were bolted together with stainless steel and galvanized hardware. The crew dug a wide, shallow pit and lined it “to make sure the frost doesn’t get under the loom,” Auciello says. Then they reinforced the pit with a cage of rebar, drilled through the two legs of the loom and tied them into stainless-steel rods.

Weighing about 1,400 pounds, the loom was erected using a tripod and braced into position. Then the stone masons poured 6 inches of concrete, leaving enough depth to completely cover the foundation with soil so that the sculpture “appears to come right out of the earth,” says Auciello. “With the way we erected it, the loom shouldn’t move for a few hundred years.”

Weaving at the Fair

The process of preparing the granite EarthLoom for weaving is the same as it was for wooden iterations. Each morning before the Fair begins, Merrill runs long vertical strands (called the warp) of jute twine from the top to the bottom of the loom, alternating between brown and green strands. In the middle she warps a strand of red jute so that weavers have a visual understanding of the center of the weaving.

With this setup, weaving on the loom “simply becomes a matter of picking up the brown and then picking up the green,” Merrill says. The Wednesday Spinners choose the recipient of each weaving, typically a person unable to attend the Fair. Weavers create a tapestry each day of the Fair, after which Merrill removes the work and binds of the edges. The first EarthLoom weaving, from the 2005 Fair, hangs in the entryway of MOFGA’s main building in Unity.

Merrill keeps the pocket park stocked with weaving materials such as yarn and fabric pieces, placed in separate baskets around the foot of the loom, so that weavers can choose material for their weft (the horizontal strands). She also encourages fairgoers to find any natural materials to weave into their shared creation. They frequently use grass, straw, flowers, stalks and even pine cones. Weavers sometimes incorporate handwritten notes addressed to the recipient of the weaving.

“The weaving process is intuitive and self-evident,” Merrill says. “Everyone knows how to weave on this loom. No one needs teaching.” Because of its size, the loom can accommodate up to 20 weavers who can work from both sides simultaneously, and because of its simplicity, all ages and abilities can participate.

“Weaving together,” Merrill says, “is so powerful. It is a literal act of weaving together the community. In this simple and ancient art, we connect with others whose fingers have touched the same threads to create the same fabric with the same purpose. It is a deep-rooted bond in the heart that can change the way we define our neighborhood.”