|

| A panel of experts addressed the issue of pesticide use in schools at the Common Ground Fair. From left to right: Maine’s IPM Specialist Kathy Murray; Willow Wetherall, U. of M. student; Ann Fuller from Mass PIRG; Sharon Tisher, President of MOFGA and U. of M. faculty member; and Sandra Haggard, professor of women’s studies and biology at the U. of Maine. In front are, left to right, Alison and Anna Tsomides, children of Kathy Murray. English photo. |

By Jean English

Our children spend six to 10 hours a day in schools, many of which are poorly ventilated. When they go out for recess or stay after school for sports, they are more likely than adults to have their feet, knees and hands contact the ground, and they are more likely to put their hands and other objects in their mouths than are adults.

As they play or study, we parents don’t know what chemicals they’re contacting or ingesting. “There is no notification requirement regarding pesticide applications at schools,” said MOFGA president Sharon Tisher at MOFGA’s Fourth Annual Public Policy Teach-in at the Common Ground Fair.

Tisher cited the Natural Resources Council 1993 report that showed that “children are not just little adults” when it comes to pesticide exposure. “Children are qualitatively and quantitatively different in their reactions to pesticides in foods,” she said. “Their brains are developing through the age of 12, with specific times when they are especially sensitive to pesticides. Organophosphates and carbamates are especially dangerous to them. Whatever levels [of pesticides] are toxic to adults, [these levels] are 10-times more toxic for children.” Children’s health was not considered when standards for pesticide residues were established.

In 1993, Tisher continued, the Environmental Working Group found that children consume far more of certain types of foods than adults do, and that millions of children receive their lifetime “allowable dose” of some pesticides by the time they are 5 years old. “The Food Quality Protection Act is trying to change that, but our kids will be young adults by the time those changes occur.”

Not only are children subjected to more pesticides in foods than are adults, but they are also subjected to pesticides at school. A 1991 study, said Tisher, found that 87% of the schools in New York used pesticides.

To discuss ways to reduce or eliminate pesticide use in schools, MOFGA invited four experts to speak at Common Ground. They were Ann Fuller, a Bates graduate who now works for Mass. PIRG (Public Interest Research Group); Kathy Murray, our state IPM specialist and formerly an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Maine; Sandra Haggard, a professor of women’s studies and biology at the University of Maine; and Willow Wetherall, a UM student who took one of Haggard’s classes.

Legislation Pending in Massachusetts

Fuller began by telling fairgoers that Mass PIRG has been focusing on pesticides for the last three years. “Pesticides are commonly being used where students spend a lot of time,” she said – ”schools, playgrounds, daycare centers – and almost always without notification to and consent of the parents of the children. Safer alternatives exist.”

Mass PIRG was seeing improvements in schools Because of its educational efforts, but not enough, so it filed the Children’s Protection Act with the state Legislature to eliminate unnecessary use of pesticides in schools and daycare centers. The legislation, if passed, would allow only antimicrobials, tamper-resistant bait stations, and low-risk dust or gel products in places where children are not active. Outdoors, pesticides could be used only if an IPM program were in place, and no known carcinogens could be used. Some pesticides would be allowed for emergency uses only, and applications would be preceded by 48 hours notice to all involved.

Because exterminators and pesticide manufacturers were able to block the passage of this bill in the Mass. Legislature, the question will be put directly to the voters on the 2000 ballot if 100,000 signatures are collected in time. “If it passes, it will be the strongest legislation in the nation” relating to schools, said Fuller.

Currently, Maryland and Connecticut require parental notification before pesticides are applied in schools, and Los Angeles, San Francisco, Albany and Buffalo have ordinances regarding phasing out pesticide use.

Efforts in Maine

Kathy Murray pointed to the numerous challenges that schools face, such as asbestos, the general safety of children, and violence. “They need help thinking about another thing,” she said.

She pointed out that by Maine law, anybody who applies pesticides in schools must be a licensed applicator, even if that person is just spraying an over-the-counter pesticide for wasps.

She also pointed out that pests themselves can pose hazards to children. Cockroaches, for example, are well known allergens and can cause asthma. “Integrated Pest Management is a way to take a systematic approach regarding identifying and controlling pests,” she said. Some IPM methods include sanitation and building repair, such as repairing screens at schools; cultural practices; traps to monitor and remove pests; and the judicious use of pesticides.

Currently, half of the states in the United States have formal IPM programs in place for schools, and they are mandatory at schools in nine states. Also, two Congressional bills have been proposed that would affect pesticide uses around children.

Maine is looking at this issue by surveying schools regarding pesticide use (in January of 2000), then beginning a pilot outdoor IPM program (in the spring of 2000), followed by guidelines for applying pesticides outdoors at schools (fall 2000) and, finally, formalizing the Northeast Indoor IPM Guidelines (fall 2000).

Murray listed the following steps for establishing IPM programs at Maine’s 722 public and more than 50 private schools:

1. Develop an official IMP policy and plan;

2. Designate pest management roles;

3. Obtain training;

4. Establish site-specific goals (Do you need a great football field with no grubs in it, or just a grassy area where small children can play?);

5. Set action thresholds (Much of the research for setting these already exists.);

6. Use IPM strategies;

7. Monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the program.

How can you get such a program started at your school? Murray suggested talking with school administrators and staff; requesting notification of pesticide applications; enlisting support for IPM from your PTA, school board and fellow parents; and contacting Murray at the Maine Department of Agriculture for further information. Her number is 287-7616.

Sharon Tisher pointed out that by following the types of steps that Murray outlined, a school in Lexington, Mass., went from making monthly applications of chemical pesticides to one application in six years.

|

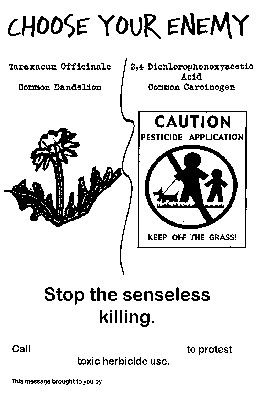

| Copy of a poster that Willow Wetherall and other students put around the U. of Maine campus after 2,4-D was applied to lawns. The number to call and sponsor of the message have been left blank in this poster so that other organizations may copy and use the it for their own protests. |

U of M Student Protests Herbicide Applications

Willow Wetherall described herself as a “super senior” (a 5th-year senior) at the University of Maine and as an activist, primarily relating to women’s issues. “But pesticides is a women’s issue,” she said.

She was taking Sandra Haggard’s class on Women, Health and the Environment last year, and within two days of starting the class, “little signs about pesticide applications appeared on the grass. The signs stayed up for a maximum of one day. Right after the herbicide application, a strange smell was noticed.” A number of students commented that they had headaches and a metallic taste in their mouths.

“The next day, there were no signs, and people were eating on the mall, and children were playing there. The space had been sprayed with 2,4-D the day before,” said Wetherall.

After the spraying, the dandelions “sort of withered,” said Wetherall, and then, oddly, the grounds crew “dug them up,” making the herbicide application even more questionable.

To raise awareness about the issue, Wetherall and other students looked up the health effects of 2,4-D and of dandelions. “It was pretty clear which was more dangerous,” she said.

She and her partner designed and posted signs to raise awareness of the issue and to provide people with the number of the grounds department as a way to protest. Many students sought her out afterwards and told her about their experiences. She believes the signs “let people know why they had the reactions they did.”

Prof. Haggard said one of her goals in Women, Health and Environment was to “try to generate cultural change in our relationship to pesticides; in our concept of what a pest is.” She believes that the current concept of a pest, such as viewing dandelions as an enemy, is an artificial concept, and she was pleased that some of her students took on the job of enlightening the university community. (Haggard’s course will be taught again during the spring semester at Orono.)