|

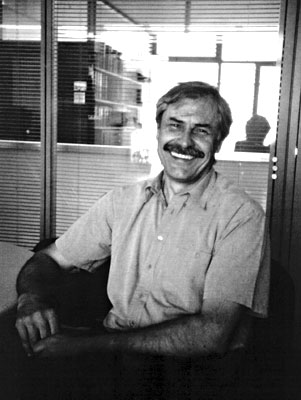

| Hans Hosbach, head of the biotechnology section of BUWAL, Switzerland’s environmental ministry. Sharon Tisher photo. |

By Sharon Tisher

Last April, a story was zapped to me over the internet about a Swiss prohibition of trials of genetically modified maize and potatoes. According to Hans Hosbach, head of the biotechnology section of BUWAL, Switzerland’s environmental ministry, this made Switzerland “a unique island within Europe, where most states, including neighboring Germany and Italy, permit growing genetically modified crops.” Since I was planning to visit Switzerland this summer, I decided to look up Hosbach in Bern, Switzerland’s capitol city.

I met Hosbach in a brand new, four story, steel and glass government office building on the outskirts of Bern. Bureaucrats in white shirts (all men, as far as I could see) strolled the halls carrying espresso in white porcelain cups and saucers, and a wetland destroyed in construction was being dutifully recreated in an adjacent lot.

BUWAL is the Swiss ministry for the environment, forests and landscape – not for agriculture or wildlife, which are handled in other departments. Hosbach, a lean, fit, fiftyish man with a bushy mustache and a broad grin, is a microbiologist who received his doctorate from the University of Zurich and then spent some years in the 1970s on a post-doc fellowship in genetic engineering at the University of California.

Along with many of his colleagues at UCAL, he had the opportunity to work for the biotech company Genentech when he completed his fellowship, but decided instead to return to Switzerland to accept a government post. He commented with bemused irony about the recent revelations (Science, June 11, 1999) of alleged theft by a Genentech employee of research DNA for development of genetically engineered human growth hormone from a UCAL laboratory, and alleged fudging of a research report to patent the material. Hosbach admitted that he did not regret his decision to work in government rather than the biotech industry.

I queried Hosbach about the process that led to the decision to deny the application of Pluess-Stauffer, a Swiss/German joint venture, to plant genetically engineered maize, and the application of RAC, a federal research institute, to plant transgenic potatoes.

Were these applications for commercial cultivation, or for test plots?

They were applications for test plots as a prelude to commercialization. They were to be quite small – no more than 2000 square meters.

Were these the first applications for transgenic crops that you have received in Switzerland?

No. Back in ’91 or ’92, there was an application for transgenic potatoes. We had no procedures then. The office of Agriculture decided to approve it. There was some opposition from Greenpeace, but it happened – for two seasons. Since then there had been a de facto moratorium. No new applications came.

Then what prompted these new applications?

We had a citizen initiative – a process where the citizens by vote attempt to pass a national law. The initiative called for a complete ban on planting any transgenic crops. It also called for a ban on issuing patents for plants and animals, and a ban on transgenic research on animals. The initiative didn’t pass, because of the part of it that called for the ban on research – all medical research involving genetic engineering would have been prohibited. When the initiative failed, then came these two requests. It seemed the way was open….

What was the process of reviewing these applications?

Since the first time in the early ’90s, we had procedures in place. BUWAL is the primary approving agency. But we must also consult the departments of Public Health, Agriculture, and Veterinary, which each has the right to veto the application. We also have an expert committee on biological safety and an expert committee on ethics in genetic engineering. These committees, along with the Canton in which the research is to take place, consult with us but do not have the power of veto. There was much opposition to the applications, from Greenpeace, World Wildlife Fund, and local organizations. The applicants for the corn trials had chosen an unusual place to conduct the trials. They were not proposed for an agricultural zone, but on property owned by Pluess-Stauffer which was in the middle of a neighborhood, a residential community. The residents were very upset about this kind of experiment being conducted in their midst.

What considerations led to your denial of the corn application?

On the one hand it was a clear political decision. The place for the trials was not good. We didn’t want to have this corn in Switzerland. The main reason we justified the denial was pollen contamination. Pollen could fly from one field to the next. This could not be completely avoided. Neighboring families could be growing corn for food and it could be contaminated by the genetic trials. Pluess-Stauffer said they would set up a buffer zone of traditional corn around the trial plot. We tried to determine how large a buffer zone was necessary. The expert committee said 200 meters would be sufficient. Then other experts we consulted said one needed 400 meters in the main wind direction. The Agriculture ministry said you should castrate this maize – cut off all male flowers. In the end there was no sound scientific basis to say in Switzerland 90% of pollen would fly no more than 200 meters, 400 meters, etc. We denied the application because of this uncertainty about contamination.

You mentioned your Agriculture ministry’s proposal to “castrate” this corn. I take it then your Agriculture officials were not sympathetic this time to these applications?

Agriculture was really very concerned, not very pro. A few weeks after the denial, we had a serious corn contamination problem. Corn seed contaminated by a genetically engineered variety was imported to Switzerland. It was sold, not checked at the border, some 400 hectares (about 1000 acres) were planted. We determined that the corn had to be destroyed. We requested that Pioneer Hi-Bred, the source of the genetic contamination, pay all the costs of the destruction. They paid. Swiss agriculture lives on our product’s reputation for being pure and close to nature. These gene technology experiments affect this image. This can have far reaching impact on our agricultural sector.

What was the basis for the denial of the potato application?

The potato had an active antibiotic as a marker gene. We determined that there was no real use for the antibiotic marker gene, and it added to the risk of development of resistance to antibiotics. So the risks of the use of the marker gene clearly outweighed its benefits. This is a serious problem. Resistance is growing to antibiotics, and for 30 years we have had no new antibiotics. It’s a really dramatic loss of a resource. In Switzerland we use 1000 tons of antibiotics a year in agriculture, we use far too much. Eighty percent of the antibiotics used in agriculture serve no real purpose, and 50% of antibiotics in human use is nonsense. There is no usefulness to antibiotic marker gene engineering.

I was intrigued by your ministry’s denial of these applications, because Switzerland is a relatively small country, but home of the largest agrichemical corporation in the world – Novartis. Novartis is a giant in the genetic engineering field. What influence did Novartis try to exert with respect to these decisions?

In these specific cases they had no influence at all. In a general way, they have of course been very involved in these issues. When the citizen initiative was pending, Novartis opposed it, and submitted to Parliament an alternative legislation which would address the process for consideration of applications for release of genetically engineered organisms. The Novartis proposal was approved by Parliament and had some influence on the failure of the citizen petition. The legislation contains some general standards which will have to be interpreted by us on a case by case basis. For example, in approving release of genetically engineered organisms, we must respect the “principle of dignity of creation.” If your genetic modification may touch the inherent value of a form of life, you have to justify ethically why you do it. This might preclude approval of the terminator technology. You must also demonstrate that your technology is consistent with protection of biodiversity, sustainable use of natural resources, and safety for man and the environment. And the legislation extended the statute of limitations for liability from genetic engineering to 30 years. And instead of “informing” the public, you must have a “dialogue” with the public.

So these standards will guide your consideration of the next GE applications?

There will be no new applications. I believe there will be no new applications for the next few years, as a result of the vote on the moratorium in the European Union.

What was that?

On June 25, the European Union voted on a proposed moratorium on growing genetically engineered crops. The proposal failed, with six countries opposed, five in favor, and four abstaining. The countries which favored the moratorium were France, Spain, Greece, Denmark and Luxembourg. (Switzerland is not a member of the European Union). Germany was the main opponent of the moratorium. However, the vote demonstrated that there was clearly not a majority of member states in favor of approval of new genetically engineered crops. If a country comes to the EU with a proposal for a new crop to grow and distribute in Europe, it will need a majority of members in favor. With this vote, it is clear that it will not be approved.

How does this affect GE crops that have previously been approved for cultivation in Europe?

It will not affect them. They will still be grown.

When you were considering these applications in Switzerland, did you have any communication with Dan Glickman, or others in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, attempting to support the applications?

Under the World Trade Organization, we have to give notice to the U.S. of our intention to deny such applications. They have a right to comment. But they are always very polite, the Americans. Very polite. “Might you be aware of…;” “ Perhaps you have not considered…;” We have to reply, and that is that. This was not a big problem because Switzerland is not a very big market. To Monsanto it doesn’t really matter if the whole of Switzerland is organic. To Novartis it is a little more embarrassing….

What has always puzzled me is the difference in perspective on genetic engineering in Europe and in the United States. Many in the U.S. still believe genetic engineering will save the world, feed the starving masses…. Europe is far more skeptical about the environmental consequences. How do you explain these differences?

I don’t know. I don’t know. But I can say that the perspective in Europe will have a severe impact on the U.S. The coalition of food manufacturers and retailers who have pledged to eliminate GE foods from their products – including Marks & Spencer, Sainsbury – represent 25% to 50% of the European market. They are looking for new sources of corn and soy that are not genetically engineered. They are finding them in Brazil. This will definitely impact American producers.