Responding to the Milk Price Crisis

By Jon Walsh

The past few years have been difficult for organic dairy farmers in New England. After years of relatively high price premiums and steady consumer demand, the milk price began a steep decline in June 2016. As processors confronted a massive oversupply of organic milk, they began implementing production quotas and volume restrictions, selling excess milk on the conventional market. Unlike previous market slumps, this situation remains unresolved almost three years later. By the beginning of 2019, the average milk price paid to organic dairy farmers was down by 25 percent, with no signs of improvement in sight. Some observers have begun to wonder if the era of viable small-scale organic dairy farming has ended. To help consumers and producers better understand the situation, this article explains the economic causes of the current crisis in organic dairy and identifies some policy solutions that have been proposed to make organic dairy viable again in 2019.

Background

For many years organic dairy has been the fastest growing U.S. agricultural sector. Driven by ever increasing consumer demand, organic milk producers have typically received prices well above those paid to conventional dairy producers. Organic prices have also remained fairly consistent compared with the wild ups and downs of the conventional market. These economic factors have enabled many small dairy operations to stay in business.

Organic dairy producers traditionally have enjoyed higher prices partly because many consumers have been willing to pay more for products with a lower environmental impact and high animal welfare standards. While organic milk is sold as a commodity product, it is held to stricter standards than conventional milk. These rules are set by the USDA National Organic Program (NOP), with farms certified by local agencies such as MOFGA Certification Services LLC (MCS). The NOP requires that organic dairy cows spend at least 120 days on pasture and receive at least 30 percent of dry matter intake from pasture each year. It also limits synthetic inputs and mandates strict restrictions on antibiotic use. Organic standards, while raising the cost of production, have helped small-scale dairy producers by making it harder for factory farm operations to enter the organic milk market.

|

What Is the Crisis?

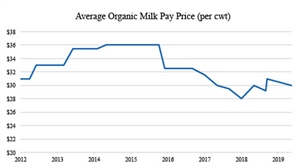

Between 2008 and 2016, organic milk prices increased steadily, reflecting increased consumer demand. While high organic production costs meant that profit margins were still small, organic farmers could rely on steady price increases. The above graph shows that this began to change in 2016. Between June 2016 and October 2018, the milk price had reduced by 25 percent, or almost $8 per hundred pounds of milk. This massive reduction was accompanied by a wave of production quotas and contract cancelations as processors were unable to find a market for the milk.

For many organic dairy farmers with tight margins, this market slump has been catastrophic. Jacki Perkins, MOFGA’s organic dairy and livestock specialist, has been working closely with Maine farmers throughout the crisis. As she says, “Organic dairy farmers are barely breaking even.” As farmers struggle to stay afloat, “there is no room for infrastructure improvements, large herd health emergencies or feed shortages.” At the same time processors have continued to impose quotas, to end contracts and to eliminate entire truck routes. Many farmers have had to make the difficult decision to stop milking. While some producers have been able to rely on savings or debt to stay afloat in the short term, without some kind of economic relief soon, many more will be forced out of business.

What Is Causing the Crisis?

Unlike conventional milk, organic milk prices are not set by the federal government, so they are more influenced by the market forces of supply and demand. Given the growing market for organic milk and the higher cost of production, organic farmers receive more money per unit of milk than conventional farmers do. However, this also means that each farmer has to negotiate an independent price contract with his or her milk buyer.

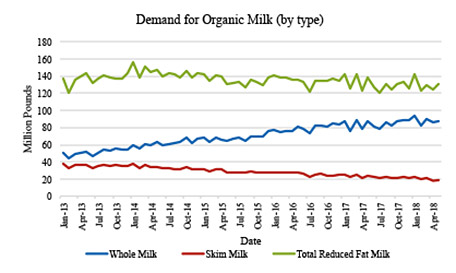

Ed Maltby, executive director of the Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Alliance (NODPA), has watched the organic dairy market for years and explains that the current crisis can be best described as a combination of slowing growth in demand and dramatic market oversupply. On the demand side, while organic whole-milk sales continue to increase, reduced-fat milk sales are declining by 1 percent per year. At the same time many consumers have switched to plant-based milk alternatives. The result has been level demand for organic milk, an unexpected trend after many years of steady market growth.

|

Unfortunately organic milk buyers were caught off guard completely by this sudden leveling of the market. A moderate supply shortage between 2014 and 2015 had raised organic milk prices to a record high $36 per hundred pounds. Assuming continued growth, milk buyers such as Organic Valley and Horizon responded to these strong prices by signing new contracts and encouraging more farms to start the multi-year process of transitioning to organic certification. At the same time, large western dairy operations were also responding to high prices. As Maltby explains, “In 2015 we saw a rapid increase in production from large-scale dairies using loopholes in the NOP pasture regulations and the origin of livestock regulations to increase supply quickly and cheaply.” These loopholes, made possible by inconsistent enforcement of USDA organic standards by local certifiers, included “continuous transition” of conventional animals to organic and insufficient use of pasture forages, according to Maltby. Market trends toward shelf-stable, store-branded milk helped these industrial-scale milk producers compete directly with small producers across the country.

The results of this expansion in production were dramatic. Between 2015 and 2016 the total number of organic dairy cows in the United States grew by 15 percent, greatly increasing the amount of organic milk on the market. Unfortunately for New England buyers, growth in demand had already peaked, and traditional organic processors such as Organic Valley and Danone NA had too much organic milk. “If milk buyers had judged the demand side better, they would never have expanded their pools of milk,” Maltby says. By June 2016, price reductions, quotas and volume restrictions were the inevitable consequence as processors scrambled to cut their losses.

Through 2017 and 2018, the factors leading to depressed milk prices did not change, and farmers have continued to struggle. By spring 2019 the markets had stabilized somewhat, with production levels more closely balanced with demand. However, cheap milk from large organic farms continues to depress prices, and the situation seems to have reached a new low equilibrium. The unabated trend of low organic milk prices has led many to conclude that the economic situation for organic dairy farmers will not change without some kind of shift in policy. Fortunately for farmers, a variety of stakeholders in New England are working hard to find a solution to this ongoing crisis in organic dairy.

How Can We Solve It?

Like many economic problems in agriculture, finding a way to improve the price situation for organic dairy producers will be difficult. While consumers can do their part by buying more organic dairy products certified by reputable organizations such as MCS, most stakeholders agree that any real improvement will have to come from the supply side. Most proposed ideas relate to policy, infrastructure and farmer assistance.

Regarding policy, almost all organic stakeholders agree that inconsistent and poorly enforced organic certification standards are a major culprit in the current price crisis. Any improvement here would go a long way in helping small organic dairy producers earn a higher price. First, the USDA should be pressured to issue a new Origin of Livestock rule so that farms can transition animals only once rather than continuously. Second, the NOP should be pressured to enforce existing regulations to ensure that all producers are held to the same production standards. If the NOP holds producers to its own standards, the flood of cheap “organic” milk currently holding down the organic milk price could be abated. Maltby suggests pushing for national congressional legislation to mandate stricter certifier audits (including increased field inspections) and congressional oversight of organic standards as one way to achieve this.

In addition, producers and advocates for organic dairy have proposed changes to the current pay price structure. One idea proposed by NODPA is to develop a cost-plus pay price solution in which the cost of production is a key part of the price formula for milk buyers. While this type of change would be difficult, one example of how this might work is the tier program familiar to Maine dairy farmers. This program provides a subsidy to farmers when the milk price dips below the cost of production. Because the organic price is not currently set by a government entity, building this type of plan would require close cooperation between organic buyers, farmers and government entities.

Regarding infrastructure, another set of ideas involves enhancing milk transportation and processing infrastructure. This is particularly important in Maine, which currently has no in-state milk processing facilities. This leaves farmers vulnerable to being dropped anytime an out-of-state processor decides to change its market strategy. To address this issue, the Maine Farmland Trust (MFT) and a number of partners are working on an economic feasibility study on in-state processing for organic milk. Ellen Griswold of MFT explains the rationale for this approach. “The previous sales of an in-state organic processor, which closed in 2014, showed strong consumer support for a Maine organic milk brand. Given the demonstrated consumer support and producer need for local market access, it seems the optimal time to investigate the feasibility of establishing in-state processing to enable better market stability for organic dairy farms.”

Other ideas have included creative shifts in milk transportation infrastructure. A recent conference presentation by NODPA explored the possibility of milk collection stations, centers where small milk loads are aggregated and picked up by one large tanker truck. Another creative proposal from this presentation was the idea of non-branded milk truck routes for commodity organic milk producers. Assuming consistent regulations and standards, this approach would reduce transportation prices in order to maximize the farmer share of the retail price.

Regarding technical assistance, while the above ideas hold great promise in the long term, both policy and infrastructure improvements will take time to develop and implement. In the short term, the best approach to mitigate some of the effects of the organic dairy price crisis may be through farmer technical assistance programs. Fortunately organic dairy producers in New England have access to a variety of organizations dedicated to supporting farmers, including MOFGA, NODPA, MFT, Cooperative Extension and others. Technical assistance to dairy farmers can take many forms, including pasture and forage management advice, financial and business planning services, and nutrition advice. Building on farmers’ own knowledge, outside assistance can help organic dairy operations reduce costs, increase milk quality (and pay price) and manage risk.

While 2019 is likely to be another tough year for organic dairy producers, innovative ideas proposed by the organic dairy community should give some hope to dairy farmers across the region. Consumers also have an important role to play – buying local dairy and demanding consistent, fair enforcement of NOP standards to help end to the flood of cheap organic milk. New England’s regional organic food system depends on keeping organic dairy farms in production. A combination of policy, infrastructure development and technical assistance may enable a recovery from the current crisis and help organic dairy farms thrive once again.

About the author: Jon Walsh is from Winslow, Maine, and now lives in Burlington, Vermont. He writes about organic agriculture, economics and policy and has a master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Vermont, where he has researched organic dairy farm viability since 2016.