|

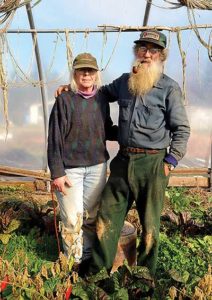

| Lois Labbe and Tom Roberts were the farmers in the spotlight at MOFGA’s 2018 Farmer to Farmer Conference. |

|

| Sam Gerry (left), Jess Moquin (right) and their son, Malachite, are part of the Snakeroot crew. |

|

| Labbe’s daughters, Debbie Ferguson (left) and Lori Labbe, are also involved with Snakeroot Farm. |

By Jean English

Photos courtesy of Snakeroot Farm

Tom Roberts and Lois Labbe of Snakeroot Organic Farm in Pittsfield were the “farmers in the spotlight” at MOFGA’s 2018 Farmer to Farmer Conference. Sam Gerry, who works at Snakeroot, joined them.

Roberts started working at Peacemeal Farm in Dixmont in 1980, when he was 35. Labbe met him in 1990, when she lived near Augusta and worked as a registered nurse. She was 45 years old then and had never farmed. She soon moved to Peacemeal, where Roberts’ mother was also living. They were looking for their own farm when a realtor said she had the perfect piece of land for them.

“Tom’s mom and I trekked in there” to find an open field with a southern exposure, said Labbe. “This is the place!” they both said. “With a lot of family help we invested a lot of money at the beginning and got it all paid off. I learned a lot at Peacemeal and from reading and talking to others.”

The couple started Snakeroot Organic Farm in 1995 while they were still at Peacemeal, the year before moving to Pittsfield. The history of the farm and thorough descriptions of its practices appear on their encyclopedic site, https://snakeroot.net/farm/.

The 8-acre opening in the woods in Pittsfield was growing timothy and red clover. It was 3 miles from town, down a rough, 700-foot woods road. The first year they spread lime from a bulk truck and then rototilled and planted two successive crops of buckwheat to shade competing grasses. In the fall they planted oats, and in the spring of 1996, they cultivated vegetables on half the ground and cover crops on the rest. They now grow vegetables, fruits and perennials, and rosemary and aloe plants, thanks in part to information gleaned from other farmers.

“We’re at the stage where we have a lot of information about how to do stuff, and we want to share with new farmers,” said Roberts.

Focused Marketing

They had already been going to the Orono Farmers’ Market when they moved to Pittsfield, and they’ve continued to focus on farmers’ markets.

“I love going to farmers’ markets,” said Labbe. “Ninety percent of our income comes from farmers’ markets – Pittsfield, Unity, Waterville, Orono.”

Roberts added that about half the farm income comes from the Saturday and Tuesday Orono markets. “Having the same person at the market each week helps,” he said. “It builds relationship with customers.”

They try to create rich and enjoyable relationships at markets so that customers’ experiences differ from going to the supermarket, which Roberts describes as sterile. “When I started going to farmers’ markets in the early ‘80s,” he said, “I realized that as soon as I got out of my truck, the curtain went up and I was the farmer for the audience of shoppers. I had to play that role. No matter what my day had been like so far, once I was there I was the farmer bringing vegetables into the city. My customers wanted that performance. I should be grateful that they took time out of their schedule to come to the farmers’ market. My job was to be the most interesting character I could be and to teach them to come to the farmers’ market first instead of saying, ‘Oh, I just bought lettuce at the grocery store.’”

He wears a nametag that just said “Tom,” so when customers go home, they know their carrots came from Tom – “even though Lois harvested and bagged them,” he quipped.

“One of the reasons I like to go to farmers’ markets with a helper is that I can have that person take care of the line of customers and I can get into in-depth conversations with someone who asks, ‘What is the best tomato to grow?’ or ‘How do you use celeriac?’ if they want that depth. I try to develop interactive responses to people’s questions or comments, or start a conversation. I let my customers know that my stand is self-service.”

The first year they were at the Orono market, they noticed that customers came even in the rain, with raincoats and umbrellas. “Their dedication to going to the farmers’ market is so strong,” said Roberts. “They know the farmers are out there and want to support them. It’s like finding earthworms in your garden,” which makes you think, “I’m doing something right!”

Roberts said that if he brings home enough money and he had a good time, that’s success. He noted that agriculture predates industry by a long time. “To call agriculture an industry, I don’t like that. You shoebox it into a format it doesn’t really belong in. Being involved in agriculture has little to do with a business; it’s a lifestyle, a different way of looking at and interacting with the world. My ecosystem includes everything from my customers at the farmers’ market, to the diesel dealer, to the microbes and worms in my soil, to people in town raking their leaves in the fall and bringing them to me. The town doesn’t have to deal with 55 tons of leaves each year because they just send them to the organic farm. My job as a farmer is to fit as many of those resources in as I can.”

Asked if those leaves contain garbage, Roberts said that those picked up with mowers with a bagger are shredded and are usually clean, and whole leaves are pretty clean, but occasionally bagged leaves will have half a bag of trash at the bottom. The farmers have learned to feel the bag before dumping it.

Sam Gerry, who farms at Snakeroot with his girlfriend, Jess Moquin, noted that they don’t stand behind their farmers’ market display but set it up “so that we’re part of it. We’re walking around our display. We bring toys – snakes and bugs that we hide in the display – and every week kids and their parents venture around looking for the snake. Small things like that separate us from supermarkets.”

Labbe added that they set empty crates around their area so that people can put their produce in them and have their hands free for additional shopping.

The Simple CSA

Eventually they started a debit-style CSA plan. Customers who buy and pay for a $100 share by April 1 can buy $120 worth of goods when they shop at the market; those who pay by May 1 can buy $110 worth of goods. In January, February and March, Roberts contacts potential CSA customers through a free MailChimp account.

In the first couple of years, only seven people joined, but around 2001 the idea took off, and now over 100 customers join annually. The system has proved better than offering a box of preselected produce, said Labbe. Some customers buy more than one share; one buys eight. A summer camp in Oakland gets 10 shares so that it can buy $1,200 worth of goods at the Waterville Farmers’ Market. Camp personnel tell the farmers ahead of time what they want so that they don’t decimate the market stand supply.

The CSA customers can use their Snakeroot credit to buy from other farmers at the market who have products that Snakeroot doesn’t have. For example, they might buy meat from Cornerstone Farm using their Snakeroot CSA, and Roberts will reimburse Cornerstone. “So that’s a deduction, but we still get the money upfront,” said Roberts. He noted that they’ve been spending $4,000 to $5,000 per year on others’ products at the market, but, Lois added, “on average we’re bringing in $20,000 in the spring.”

Also, by looking around to see what the market has on a particular day, Roberts said he becomes expert at answering customers’ questions, further building that special farmers’ market relationship.

“The CSA changed our cash flow,” said Labbe. “We had plenty of expenses early in the season, but even when we started going to the farmers’ market in May, sales weren’t huge then.” Since growing spinach and other cool-season crops in the greenhouse, they’ve started going to market in late March or early April with that and overwintered produce. “Still we don’t break even until July 10,” said Labbe, but having the cash flow a little earlier means Labbe hasn’t had to do nursing work for the last eight winters.

They do not offer refunds on unspent CSA money, nor rollovers into the next year. “We keep it open until December 31,” said Labbe. “We go to winter markets in Waterville and Orono.” If someone wants to buy a share at the end of the year for the following year, they just record it as income for the current year.

They are happy with the simplicity of their CSA system. Roberts comments that “some people’s CSA plans are so complicated!”

Website Sales

“Our internet presence has been so important for us,” said Roberts. “So many websites are all fluff. A lot of them you don’t even know who the people are – they don’t put their names on them. We think that’s the wrong approach, especially if you’re trying to create relationships with people.”

He explained that Google used to use key words to respond to searches, but now it’s more interested in content and how many other websites link to yours. “The better content you have and the more you have on a page, the better Google likes you,” said Roberts, “and so do customers. If you look up ‘mulch, organic, Maine,’ we’re the first site to pop up.” Their site explains how they plant garlic, how they get leaves for soil fertility, what equipment they use, their history, and much more.

Through the website they sell tomato and Echinacea seeds and garlic. Roberts said a university professor in Rhode Island orders 200 to 400 pounds of garlic bulbils from them each year at $8 per pound plus postage. The professor freezes the bulbils at different temperatures and then revives them after one, two or six months to see what sprouts. He extracts the allicin from the sprouted bulbils in an attempt to get year-round production of the compound.

The MOFGA Certification Services site, https://www.mofgacertification.org, has helped them as well. Because it lists Snakeroot as growing horseradish, MOFGA-certified organic Split Rock Distillery asked for a couple of hundred pounds of the root to make its horseradish vodka. So the farmers expanded their horseradish patch. “We cut off all the heads so that we can replant them to expand the patch,” said Roberts. They also put smaller pieces in 2- and 4-ounce quantities in Ziploc bags to sell at farmers’ markets. “They’ll keep a long time in the bags until they sell,” said Roberts.

Snakeroot uses its Facebook page as a blog, to keep customers apprised of current news. The farmers share spreadsheets, planting and other records with one another via Google Drive.

Finding Help and Addressing the Future

Snakeroot has had apprentices in the past, and Roberts and Labbe thought that a couple that farmed with them from 2006 until 2010 might take over the operation, but the couple’s plans changed. Then Sam Gerry appeared.

Gerry had been working at a vet’s office and had a “fun garden” occupying his whole front yard, as well as about 20 chickens. Jess Moquin convinced him to try farming as a job, so he worked at Snakeroot three days per week the first year while keeping his other job three days per week. When he and Moquin had a child, he took another job five days per week and helped Roberts at market on Saturday and on the farm one other day per week. Eventually he and Moquin decided they were serious about farming, started looking at property and signed up with Maine Farmland Trust’s Farmlink program. When asked what they were looking for, they kept describing Snakeroot – a farmers’ market farm with a few acres in mixed vegetables. Roberts joked, “You’re looking for a farm with older farmers? I’m right here!” After a few months of discussion, they made a deal. Gerry has now spent four farming seasons at Snakeroot, and he and Moquin have lived at Snakeroot for two seasons. Gerry was a fulltime apprentice there last season. “I was familiar with Snakeroot as a kid,” he said. “I grew up in Pittsfield. I went from being loyal customer to loyal worker in no time.”

Labbe’s two daughters, Lori Labbe and Debbie Ferguson, are also involved with the farm. “The six of us,” said Roberts, “have been investigating ways of transferring ownership, most likely into an LLC, which will have all of us as members. But it’s a slow process that we’ve been at for a couple of years now, since it needs to deal with emotions, interpersonal chemistry, insecurities, visions for the farm, and the whole process is not without the influence of a trace of ‘founder’s disease.’”

Asked how long they had farmed before they thought they were stable, Roberts said, “We’re getting there!”