Maine farms develop indoor and outdoor set-ups for market-scale mushroom production

By Holli Cederholm

Courtney Williams of Marr Pond Farm in Sangerville, Maine, says that outdoor mushroom production is a way to manage marginal lands profitably. She and her partner, Ryan Clarke, branched into mushrooms in 2016 in order to gain “market access” to farmers’ markets already saturated with mixed vegetables and cut flowers, which they also produce, while maximizing profits from their existing land base.

Marr Pond Farm has only 3 acres of tillable land to work with, and Williams and Clarke rely on an additional 7 acres of leased fields to grow enough seasonal produce to fill their stands at the Orono and Waterville farmers’ markets three times each week. With the remainder of the farm in “abused,” heavily logged woodlands with wet and rocky soils, the pair saw an opportunity with mushrooms: They could balance rehabilitating and conserving the farm’s native forest with increasing their crop production closer to home.

Seeing the Forest for the Mushrooms

“We jumped feet first into log-grown shiitake cultivation,” says Williams.

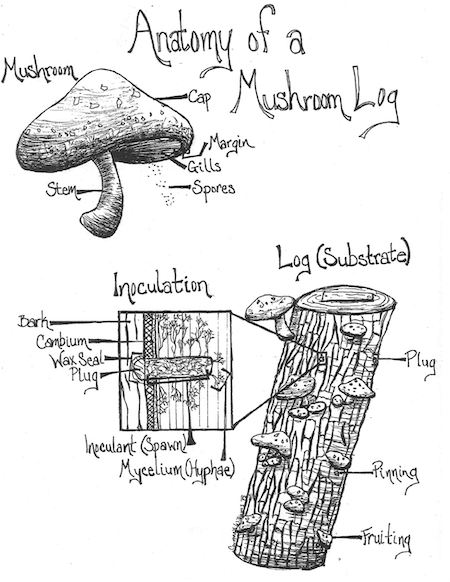

A saprophytic fungus, shiitakes can only be grown on wood, with oak being the best substrate — though other hardwoods, including sugar maple and birch, can also be used for cultivation. That first year, Williams and Clarke inoculated 200 to 300 logs with sawdust spawn containing fungal mycelium, purchased from Field & Forest Products in Wisconsin. Technically, Williams says, they’re “cultivating fungus, not mushrooms” as “mushroom” refers to the fruiting body that she, Clarke, and their crew of three to five employees harvest from June through October.

Their ½-acre cultivation yard is located near the farm’s namesake, the 80-acre Marr Pond, and relies on water from the pond to “shock” the fungus to “force” fruiting (more on that later). Situated in a swath of forest that offers shade cover year-round, it is an ideal location for fungus to grow. “Where our mushroom yard is actually has a huge diversity of natural mushroom species,” says Williams.

Entering their eighth year of mushroom production, Marr Pond Farm now maintains 2,000 logs annually. To maintain their system, they inoculate 500 new logs each year, and retire that same number to a “log graveyard” — each log produces for four to five seasons, and starts to look like Styrofoam at the end of its span. Yearly, they expect to harvest between 400 and 800 pounds of shiitakes. “The yield on outdoor mushroom cultivation can be pretty variable,” says Williams. “Part of the reason that number is so wide is because we don’t actually weigh them.” Instead, the mushrooms are packed into pint-sized berry boxes for their farmers’ market display and transferred to paper bags at point of sale; mushrooms, which lose moisture content and shrink rather quickly, store better for their customers this way.

While Williams and Clarke have dabbled in different mushroom “pets” for home use, including oysters, lion’s mane and wine caps, shiitakes are their market mainstay due to their reliability.

“Similar to vegetables, where you’ve got your Big Beef tomato and your Sungold tomato — they look really different, but they’re both tomatoes — there are different strains of shiitakes,” says Williams. They cultivate an array, including West Wind, WR46 and Jupiter, selected for their distinctive fruiting requirements. Choosing strains with different fruiting temperatures allows them to cover both cool and warm weather fluctuations, and therefore stretch the market season.

Inoculation, Log Yard Set-Up and Outdoor Mushroom Management

Marr Pond Farm harvests logs for mushroom production in the spring, ideally before bud swell and definitely before bud break, and, when possible, no longer than six weeks before inoculation, which they do early May through mid-June. Cutting logs in this timeframe will reduce incidence of bark slippage (and the logs drying out) while also helping to retain nutrients in the wood.

With an eye on thinning the forest in line with their conservation management plan, they harvest live, disease-free specimens without evidence of other fungus already in residence. “Remember, this is basically like you are planting the seeds of a mushroom into this log just like you would plant seeds of a vegetable crop into your potting soil, so we want it to be weed-free,” says Williams.

Preferably, logs are 4-12 inches in diameter. “If they’re any smaller, they’re just not going to last for very long. Basically, every year the mycelium is eating this wood.” She adds that potential producers should also consider the weight of the logs. “You have to lift them in and out of your soaking tanks,” says Williams. A 24-inch, 4-foot-long piece of oak soaked in water for 24 hours will be heavy — and may impact one’s interest in producing mushrooms long term.

It will also take longer for larger logs to fruit, as the mycelium has to colonize the whole substrate before “pinning,” or the formation of baby mushrooms, starts.

Next up, inoculation. Depending on the type of spawn used, different tools will come in handy. At bare minimum, producers will need a wire brush to scrub the logs free of lichen and moss, a drill and a drill bit with a stop collar, and a table, or sawhorses topped with some flat boards, sturdy enough to hold a log. For those planning on scaling up fungi production as part of their farm business, Williams notes that an angle grinder with an adapter on it to function as a high-speed drill and roller tables to create an inoculation assembly line will increase efficiency. If you’re inoculating more than a hundred logs, she also recommends having a few bits on hand, or a sharpener to hone the soft steel as you go.

“For plug spawn, which is kind of the lowest barrier to entry — you don’t need any special tools — other than having a way to drill the logs,” says Williams. Also known as dowel spawn, it consists of wooden rods inoculated with a specific mycelium strain. Aside from your drill set-up, you’ll need a hammer and patience. “It’s going to take you a long time,” says Williams.

At Marr Pond Farm, they opt for sawdust spawn, in part because it contains more mycelium and will result in a faster colonization. To inoculate logs with the spawn, they use a small, sturdy bucket to hold the loose sawdust, an inoculation tool to inject the spawn into the drilled holes, and cheese wax that has been approved by their certifier for organic production — which they melt using an electric deep fryer. After applying a coat of sealing wax, either with a special tool or a natural bristle brush, Williams and crew staple a metal tag, marked with the date, the strain of shiitake and sometimes the wood species, onto each log.

It takes one person about an hour to complete 10 log inoculations, start to finish, says Williams.

The logs are then layered in crib stacks in the shady mushroom yard to incubate for a year. In order to get a jump on the mushroom harvest the following spring, Marr Pond Farm uses a “forced fruiting” method, soaking logs for 24 hours in Rubbermaid stock tanks filled with cold pond water. Williams and Clarke wait until they see some natural pinning — evidence of full colonization — on each first-year log before its initial soak of the season.

They usually soak 50 to 60 logs each day, placing rebar atop the tanks to keep them submerged. The next day, they lean the logs against a homemade a-frame structure. “Typically, you will see pinning within a few days but that is temperature and strain variable,” says Williams.

After a harvest flush, they wait another six to eight weeks before resoaking a log, and will repeat this process multiple times in a season.

“Outdoor cultivation is a lot more weather-dependent than indoor cultivation, both the fruiting speed and the quality of mushrooms that you’re going to get,” says Williams.

Indoor Mushrooms at Moorit Hill Farm

Like Williams and Clarke, Josh Emerman and Elizabeth Goundie of Moorit Hill Farm turned to mushrooms as a way to diversify their market offerings from a limited land base. Marine biologists by training, after graduate school they purchased a foreclosed farm in Troy, Maine, with the intention of raising Icelandic sheep for fiber and meat. They wanted an enterprise that would bring in income while they grew their starter flock — without transitioning an inch of their open 7 acres out of pasture.

What they did have available to work with was an old, uninsulated chicken barn on a concrete slab, a remnant of Waldo County’s heyday as the so-called “Broiler Capital of the World.” Enticed by the quick turnaround of indoor mushrooms — which can be harvested in a matter of one to three weeks, depending on species and strain — they retrofitted the barn to house a climate-controlled grow station.

Operating on a shoestring budget, Emerman dismantled a modular office structure and rebuilt it inside the barn. This space is split into a 16-by-20-foot fruiting room and a 16-by-12-foot pre-conditioning area, where a heat pump helps to maintain the requisite temperature of 60 degrees Fahrenheit year-round.

The fruiting room needs to be optimized for ideal conditions, with controls for airflow and humidity, in addition to temperature. Mushrooms, like people, respire. That means that monitoring for carbon dioxide (CO2) is critical. In addition to causing tough, leggy fruit — all stem and no cap — high levels of CO2 can be hazardous. The room is ventilated with exhaust fans monitored by a sensor.

Humidification takes place in the grow room itself, with 80% humidity as the goal. “In the mushroom growing world, droplet size is really important. If it settles on the mushrooms, it will cause diseases,” says Emerman. “We’re basically keeping this room at the perfect conditions for fungal growth — the fungus that we want to grow love it, but so does everything else.” Trichoderma, neurosporo (known to Emerman as “The Farm Destroyer”), lipstick mold, bacteria, and fungus gnats (which act as vectors of disease) are among indoor growers’ top concerns.

After a few iterations of humidifiers, Moorit Hill Farm settled on a humidistat-controlled system that pressurizes tap water, using an air compressor, and blasts it through a nozzle with tiny jets. “That water comes out so small that it doesn’t settle, it just floats. It’s like being in a cloud when that room is fully saturated,” Emerman says.

To keep disease pressure at bay, Emerman and Goundie, with the help of two year-round employees, are constantly cleaning the rooms and the metal grow racks. “We’re rotating blocks in and out so they’re not just sitting there too long. We’re filtering all the air that comes in to hopefully keep the bugs out and spores out,” says Emerman.

A Decentralized Approach

As a small-scale operation without a lot of space and specialized equipment, Moorit Hill Farm doesn’t, however, maintain a sterile setting. Instead, they take a collaborative approach to mushroom farming and rely heavily on a local company, Maine Cap N’ Stem in Gardiner, to produce certified organic spawn and inoculated substrate in pristine lab conditions.

“The incubation space that you need for indoor cultivation is at least three times the size of your fruiting space because you have to have a succession of blocks that you’re starting every week colonizing to be ready to fruit,” says Emerman.

At Moorit Hill Farm’s scale, it doesn’t make sense to maintain such a large climate-controlled space. “That’s where this decentralized model really works,” he adds. “They specialize in the clean lab environment for inoculation and then the warehouse space for incubation, and we, on the farm, with sheep and chickens and dogs running around, don’t need a sterile lab space to do all that.”

Emerman and Goundie continually order ready-to-fruit inoculated blocks of hardwood sawdust. Each 10-pound block is packaged in a plastic bag inside a cardboard box. Twice a week, they open up the packages and move the blocks onto metal shelves in their fruiting room. Some mushrooms, like shiitakes, are taken out of the bag. With others, such as oysters and lion’s mane, the plastic functions similar to bark, keeping the mycelium from drying out. With those, they cut X shapes into the plastic, or top the bag completely, to allow for the mushrooms to bloom. At any given time, they have between 200 and 300 blocks in action, resulting in a weekly harvest of 500 pounds.

“The great thing about this type of production is it’s really space-efficient, really high production, but there’s a lot of labor and a lot of work,” says Emerman. It’s also a resource-heavy endeavor. Growing mushrooms indoors requires electricity for climate control, water for humidification, and a lot of labor for, as Emerman puts it, “managing that constant turnaround, constant harvesting, constant marketing and delivery.” In addition to cleaning and daily harvest, their crew also handles marketing and distribution to a network of restaurants, grocery stores and co-ops, a multi-farm Community Supported Agriculture program, and two to three farmers’ markets. In their three years of producing mushrooms, they’ve barely taken a day off.

Indoor cultivation also leads to a lot of waste in the form of plastic and cardboard packaging, as well as the spent substrate. Each week, Moorit Hill’s grow operation generates 2,000 to 3,000 pounds of sawdust — which, on the flip side, can be made into compost. In 2022, they spread 6 inches of the mycelium-rich material inside their greenhouse, and, in 2023, they plan to invest in a manure spreader to add this fertility to their sheep pasture.

“It’s certainly something to think about when deciding what your overall ethos is regarding your cultivation practices. It’s high inputs and high returns. And they require an incredible amount of care,” says Emerman. “We always joke that we raise livestock on the farm and the mushrooms are way more needy.”

This article originally appeared in the spring 2023 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.