The Essencers capture the aromas of Maine with a mobile still

By Danielle Walczak

Snow fell in Stockton Springs while Brent Holiday fired up a chainsaw. It was January and the wind, characteristic of Midcoast Maine, shook the greenhouse next to the white pine he would cut down.

With the pine gone, in a few months the rented greenhouse would be filled with sharp light, ready for Holiday and Maija Lindaas, his business partner, to begin seeding vegetables.

But removing the tree had another purpose, too. Parked nearby was a silver Honda Accord trailing a handmade still, ready to be utilized in the process of distilling essential oils from the pine to bottle and sell under the name “The Essencers.” Using their mobile still Lindaas and Holiday are handcrafting essential oils from sustainably harvested forest waste and wild-foraged plant materials.

“This is a way of creating something of value from natural materials that are often seen as waste, valueless things, especially [from] logging. People see logging slash and they’re like, ‘Oh jeez, get rid of this stuff, this big pile of brush.’ It’s kind of cool to be able to create something that is worth something to people,” Lindaas said.

The diversity of the Maine woods allows The Essencers to offer unique scents not often commercially available. Situated on the borderland between the hardwood deciduous forests of southern New England and the boreal forests of northern Maine, they are spoiled for choice. By producing their own oils and cutting out the middle supplier The Essencers can compete with the prices of large-scale essential oil producers.

“It uses a ton of material to make essential oil,” Holiday said. “So when you get to that really large scale, if it’s not done conscientiously, it’s a lot [of trees]. If you’re doing that everyday you’re going through acres really quick.”

While large-scale essential oil producers have a more standardized scent, when you buy a bottle of white pine essential oil from The Essencers, it’s the product of a singular tree in a singular season — a characteristic The Essencers hope will set them apart.

“There’s a lot of room for creativity in our sourcing,” Lindaas said.

For their oils The Essencers have used a variety of material — from a cedar tree their neighbor cut down to clear a power line to spruce tips from a friend who was making building lumber for their home.

“[There are] so many people cutting trees down in Maine for whatever reason, I don’t see us ever being like, ‘Ah man, we’re out of trees that are naturally falling down, let’s start harvesting,’” Lindaas said.

Last winter, Lindaas and Holiday began distilling logging slash in a still they built out of a propane turkey boiler, a 55-gallon stainless steel drum and a spent keg. What began as a personal project morphed into a potential business that allows Lindaas and Holiday to stay connected to the land they call home near Stockton Springs, while also being mobile.

Traveling is an essential part of everything that the duo, who met sailing tall schooner boats in Camden, does.

In late 2021 they drove to Minnesota to visit Lindaas’ family. They packed their backstock of bottled essential oils, gathered at different sites during the year, and their smaller still. They hope to distill plants along their journey, including a white pine to see how location affects the scent.

“We are battling desires,” Lindaas said. “We have grown pretty much our entire diet at one point and we do [like] the homesteading aspect, taking care of plants, getting sustenance. We also really like traveling. Those two things just don’t fit together really well so we’ve been trying to figure out how to put those back into our lives.”

The same still that allows them to move from site to site, capturing the aromas that to them feel most like Maine, also allows them to travel and the opportunity to capture new scents.

“I’m never going to be a digital nomad, I can’t sit still long enough to figure out how computers work, but I like the idea of traveling with the still,” Holiday said.

Lindaas and Holiday’s connection to land is fundamental to the work they do and what they intend to capture in the experience of their essential oils. By offering an array of scents, The Essencers hope they can educate their customers about different tree species in Maine and the benefits of going in the woods.

“Smell has such a powerful memory-inducing aspect to it,” Holiday said. “So having that smell when you diffuse essential oil in your home as a way to relax, and if you don’t have time to go out in the woods, you can bring a sense of relaxation to your time, a sense of happiness to yourself just by smelling something from the woods.”

He continued, “I think it’s really cool to teach people about the diversity of the woods. You don’t have to have a guidebook to learn, you can learn in a little more interactive way.”

Lindaas added, “It’s neat having a really tangible learning tool for people, I think both of us forget a lot of people don’t spend time trying to identify different spruces in the wild.”

The Essencers bring the distillation process, which is usually done in a large facility, to the site of the oil itself.

After Holiday felled the white pine near their greenhouse, they used a BCS tractor to chip each part of the tree that was an inch or smaller in diameter. The chipped material was put into totes — the week was so cold that it stayed frozen.

Distilling the pine into 1 gallon of essential oil took a week.

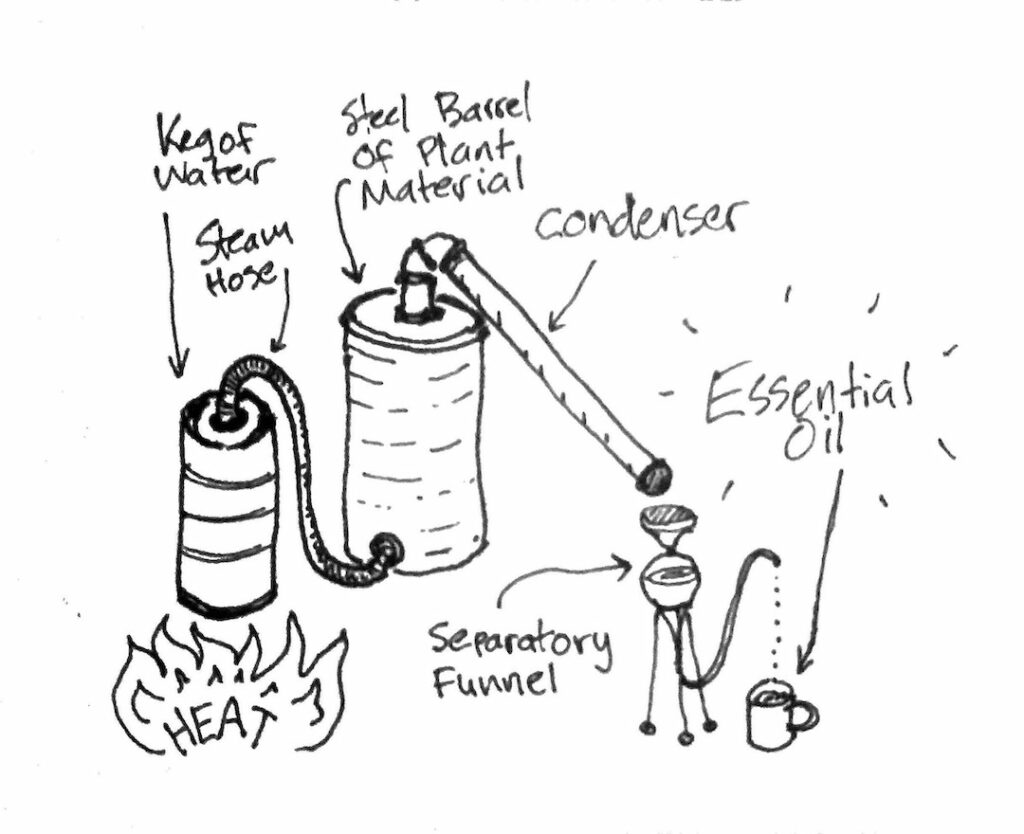

They started early each day, packing the 55-gallon stainless steel barrel with 180 pounds of plant material and locking it with an airtight lid. The barrel was attached with a hose to a reused keg filled with 10 to 15 gallons of water. They carefully wrapped the keg in a wool blanket for insulation, fired up the propane burner underneath the keg, and continued chipping while waiting three hours for the water to heat up.

Inside the steel barrel the process of steam distillation began: once the water is at a boil, steam is directed through the hose to the 55-gallon drum of plant matter. Volatile compounds in the plant matter — essential oils — also vaporize.

The steam is forced through a series of narrow 3-foot-long tubes. The tubes are encased with a water sleeve powered by a fish tank pump that helps cool the steam so it condenses back to a liquid as it reaches the end of the tubes. In the collection device at the end of the tubes water and oil separate and Lindaas and Holiday are able to collect the essential oils.

Typical stills use copper because copper reacts to the sulfuric compounds in distilled products and removes them. Because they use stainless steel, Lindaas and Holiday wait anywhere from two weeks to four months to let the sulfuric compounds evaporate.

The joy of this process glimmered in Lindaas’ description. “I liken it to alchemy,” she said.

Essential oils from coniferous trees have a long shelf life and can last anywhere from two to five years. This allows the flexibility Lindaas and Holiday need to complete their other yearly projects. They distill large amounts of plant matter in the winter and grow MOFGA-certified organic vegetables and garlic in the summer.

“It gives us more flexibility for the really hard thing, which is finding places to sell it,” Lindaas said.

The duo looks forward to returning to the Common Ground Country Fair, where they were hoping to connect with local body product producers who might want to use local essential oils.

For Holiday and Lindaas, income sources that are rooted in what they enjoy doing and that reflect their morals are important pillars of their business — as integral as sustainable sourcing.

“We’re always trying to reflect on our lives and think ‘what makes us happy.’ For me [it’s] trying all these new plants,” said Holiday. They’re excited to try distilling other plants to make essential oils, such as garlic from their farm or orange peels from a juicery. “We’re doing it because we love to do it,” he added.

This curiosity is what led Holiday to distilling in the first place. He knew he didn’t want to work in an office and realized that he liked working with herbs and keeping people healthy. “I wanted to do something different. I’m a contrarian. Farming is so main-stream now,” he laughed. “How can I work with herbs in a way that is legal and in a unique way and so I always had in the back of my mind that eventually I’d figure [distilling] out. That was two years ago.”

The couple bought their first still off Craigslist in 2019. It was originally used to distill essential oils and moonshine. Then they left for the winter.

Once back in Maine, Holiday began researching and distilling. He quickly figured out the condensing tube in the Craigslist still was too small and got clogged, leading to Holiday mistakenly blowing a hole in the bottom. Stainless steel welders were expensive.

The couple was ready to launch their business, but the pandemic hit. They worried if they got COVID-19 they may lose their sense of smell.

The pair took jobs working for the U.S. Census Bureau and saved as much money as they could so they could build their own still, and buy enough seed garlic to start growing on a larger scale.

By fall of 2020 Holiday dove deeper into anArtisan Essential Oil Distiller Facebook page,learning from the trial and error of others as well as his own. He also learned where to source parts.

When they were ready to build the large still they use today it was a big investment.

“We spent, for our scale, a high percentage of our annual income,” Lindaas said. “We don’t make very much money, our life is an order of magnitude less than what most people spend and they get.”

There was a lot of pressure both literally and figuratively to make the still work. Too much pressure and the steel barrel would explode, too little pressure and the steam would escape. They kept researching.

“Is it just going to blow a hole in it or is it going to work?,” they thought.

“It actually worked, really well, we did something right!” Lindaas said.

They began distilling with the new still in January 2021, and by March they had enough supply to begin approaching wholesale accounts.

Lindaas and Holiday’s vegetable and garlic growing operation, Frog Song Farm, is certified organic by MOFGA and, in 2021, The Essencers began the process of certifying their essential oils with MOFGA’s wild crop certification.

Wild crop certification requires a landowner affidavit of previous activity and organic practices. The producer must also remediate potential contaminants, provide buffer zones and mitigate the potential impact on plant and animal life in the surrounding area, while providing methods to protect long-term biodiversity and sustainability of the area and prevent negative impacts on the ecosystem.

“One of my favorite things about doing this is we look at trees in such a different way than we have before. You’re out dealing with a different life cycle of the tree or looking at a different part,” Holiday said.

The seasonality of trees changes how resinous they are and thus alters the essential oil.

“If you’re logging you’re not necessarily looking at the progression of the buds from dormancy to buds, or opposite, the growing of the resins in the fall, onward to the winter,” he said.

As the seasons change Holiday and Lindaas hope to distill it all.

The Essencers products are available at co-ops along the coast of Maine in Portland, Damariscotta, Ellsworth, Blue Hill and Belfast and at the Natural Living Center in Bangor. They also sell products via their online Etsy store.

About the author: Danielle Walczak is a farm worker-turned-gardener living in Portland, Maine. She writes about farming and the natural world.