By Tim King

In 1972 Ken and Roberta Horn, who were farming 140 acres near Plymouth, Maine, became the first of thousands of farms to be certified organic by MOFGA over the next half century. There were 26 more certifications granted by MOFGA that year. The number nearly doubled, to 47, the following year.

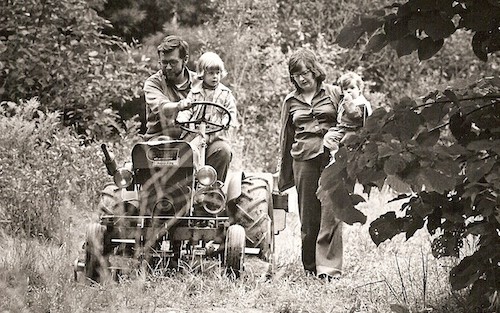

Ken-Ro Farm in 1976. Ken and Roberta Horn were the first to have their farm certified organic by MOFGA. USDA photo, courtesy of Ken and Roberta Horn

That growing interest in organic certification in Maine didn’t appear magically. The Horns, who grew up in Buffalo, New York, were among the many people of their generation to be inspired by Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” as well as the pioneering work with organic agriculture and nutrition being done by J.I. Rodale, founder of the Rodale Institute, and his son Robert. The Horns, who both took teaching jobs in Maine after Ken’s Air Force discharge, decided to walk the talk and buy a farm with a Veterans Administration (VA) loan. So did others with limited farming experience. It was the era of Agent Orange, DDT and the Green Revolution and action was required. But it wasn’t easy.

“We looked around for information about how to get started organically and couldn’t find anything,” says Ken Horn, who originally just wanted a quiet place with a garden. “You’d go to the Extension offices and they knew nothing and some were negative about it. So farmers started to turn to each other and become sources of information.”

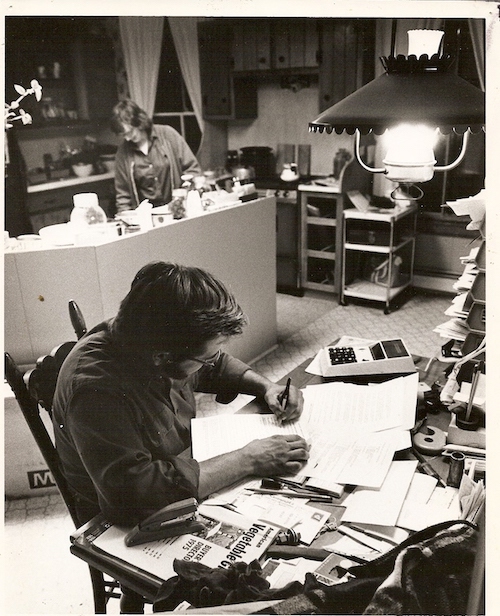

Roberta and Ken Horn in 1976. USDA photo, courtesy of Ken and Roberta Horn

The farmers became the experts in organic agriculture as they studied what Rodale published and put it into practice in their fields and gardens. When they weren’t farming they were getting together to share what they were learning and to organize what first became the Maine Organic Foods Association, in 1970, and later became the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association following a pivotal meeting in 1971. Ken Horn was elected to be president.

The members of the new organization decided to work with the University of Maine Extension Service to spread the word about organic practices.

“One of the things that helped us expand [organic agriculture] was our ability to have Extension agents come to the farm and see what was actually happening on the farm,” Ken Horn says. “We were growing good crops and we invited agents to see that it actually worked.”

When they saw that the organic practices worked, some of the agents became more open to organic, even though the practices were occasionally unpopular with some members of the general public. One agent, Charlie Gould from Androscoggin County, became a leader and was among a group that the Rodale Institute invited to speak at a conference in Pennsylvania.

“Rodale got word of us and I spoke and I think Charlie and Jim Luthy spoke,” Ken told Pauleena MacDougall in a 2003 oral history interview, which is part of the Maine Folklife Center’s MOFGA Collection archived by the University of Maine. Luthy was an organic farmer with a Ph.D. in chemistry, and, according to Ken Horn, “was getting involved in the certification process and wanted to gather more information to get certification started. When we came back Jim went off on getting certification started and I took the definition [of organic] and spoke at a lot of garden clubs, schools and even on television in an effort to tell people about organic agriculture.”

Ken Horn also traveled with University of Maine vegetable specialist Willy Earhart to extension meetings. “People would ask questions and I would give the organic side and he would give the non-organic side,” he told MacDougall in the 2003 interview. “It made for some pretty interesting discussions.”

The educational efforts paid off. In 1974 Mort Mather of Easter Orchard Farm in Wells, then serving as MOFGA’s third president, wrote in the first issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener (The MOF&G) that MOFGA had a dues-paying membership of over 300 and a mailing list of 1,000.

MOFGA also had a set of organic certification standards and a certification committee that had adopted them. The initial committee, according to the first MOF&G, was made up of a certification director, district supervisors, consumer representatives and advisors. The standards took up less than a column in the newspaper. They were simple and direct and were based on Rodale’s organic standards and definitions that Ken Horn, Jim Luthy and others had gathered on their trip to Pennsylvania.

The standards included a list of preferred soil preparations (recycled organic matter, green manure, barnyard manure, compost and seaweed), acceptable preparations (mined rock phosphate and potash as well as granite dust) and a general prohibition on chemically refined or processed additives. Preferred methods of pest control included preventing or correcting soil deficiencies, companion planting, rotating crops, using biological controls and mulching, among other practices. The focus was on soil health and organic matter.

The first issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, published in 1974, included MOFGA’s standards for organic certification.

“Applicants for recertification must have soil with organic matter content of at least 4% on plots of land on which vegetables are grown,” the standards declared. “First time certification applicants failing to meet this standard must show evidence of a strong soil building program.”

Although there were not inspections similar to what applicants for organic certification experience today, a person from MOFGA did visit all applicants’ farms.

“We didn’t have inspection as such but a MOFGA representative came to take soil samples every year,” says Ken Horn. In the early years, Luthy, who served as certification director, took the soil samples, he recalls.

MOFGA took soil health seriously and highlighted farms with some of the more stellar soils in the first issue of The MOF&G. Ralph Russell, a Tenants Harbor vegetable farmer, was one of several farms bestowed a “SuperSoil Award” with a plot testing “very high in phosphorous, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, and with an organic matter composition of 9.92%.”

For more than a decade, in addition to the soil test, if a farmer wanted to receive organic certification they’d get a questionnaire and application from MOFGA. They’d fill it out and send it back and, if their answers were in accord with the standards established by the certification committee, they’d receive certification. It was, at the time, the most sophisticated organic certification program in the country.

Although the focus on soil health and the foundational Rodale standards continued, the mid-1970s were a temporary numeric high point for MOFGA’s young certification program.

“We were first certified by MOFGA in 1985 when there were 14 farms in the program,” says Dave Colson, who raised vegetables with his parents and, later, with his wife Chris.

The Colson family, who farmed in Durham, became certified near the end of the era where farm inspections were limited to pulling a soil sample. The demand for organically grown products was growing and the market, along with the farmers who supplied it, required something more rigorous. The Colsons felt it was particularly important to the early farm-to-table restaurant market they were developing.

Shortly after the Colsons were certified, MOFGA hired Eric Sideman as an organic extension agent in 1986 – becoming the first organic farming organization to do so.

“I met Eric Sideman soon after he was hired by MOFGA, and I joined the board in 1987,” Colson says. “I believe it was either that year, or 1988, that I joined the certification committee. Having Eric on staff, and spending a portion of his time on certification, gave a real boost to the program.”

Sideman said that farmers like Dave Colson and Jim Gerritsen of Wood Prairie Family Farm in Bridgewater, who was also on the certification committee, saw the need for a farm inspection and that they were ready to embrace it.

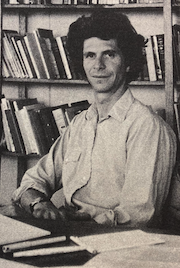

Eric Sideman, MOFGA’s crop specialist emeritus, when he first joined MOFGA’s staff; this photo was originally published in the July-August issue of The MOF&G.

“Jim [Gerritsen] had his fingers in national movements and he saw change coming,” Sideman says. “He used to say that ‘scout’s honor’ certification was a thing of the past. He was right.”

“As I think of it, the farmers wanted a verifiable program in order to assure their customers that things were legit,” Sideman continues. “The word organic was becoming very popular and was getting a premium in the marketplace. There were folks using the term in the marketplace who had no understanding of what it meant, and no third party verification.”

Having annual inspections for new and renewing applicants for MOFGA was approved by a meeting of the MOFGA membership and adopted by the certification committee. Inspections for certification and recertification became MOFGA policy in the mid-1990s.

“The inspectors were sent to the farm at least once a year to verify that the practices in the application were what was happening on the farm,” Sideman says.

In addition to adding inspections, Sideman, along with the guidance of the certification committee and the membership, began to beef up the original standards. But the focus on soil health remained central to certification.

“The key was that certification is not about what is prohibited,” Sideman says. “Lay folks think of organic as farming without pesticides or chemical fertilizer. But, it is based on what is required. Organic farming is based on farm practices that maintain and improve the soil. The original standards explained these broadly but the new application asked for detailed descriptions. For example, the farmer had to describe their soil fertility management and crop rotation practices in detail.”

The fact that there were now inspections didn’t affect the congenial nature of the certification process, according to farmers who participated in the process both as farmers and certification committee members.

“I remember reviewing when we would all gather [at MOFGA’s office] in Augusta or different places,” says Jason Kafka, another certification committee member and a vegetable farmer and greenhouse operator at Checkerberry Farm in Parkman. “The roof in Augusta leaked when it rained. There were five-gallon buckets collecting the rainwater. Now we can meet at our Fair site in Unity.”

“It was a much smaller and cozier group and we didn’t have the Feds to contend with. We had our rules and it was a smaller community too. We knew each other so there was kind of a self-policing going on. I think we were all kind of organic purists anyway,” says Kafka.

Colson agrees with Kafka’s assessment.

“We were a small group and the number of certified farms grew, but it was still less than 50 farms. We didn’t certify livestock or processed products at that time,” says Colson. “Often we would convene once a year at Rob Johnston’s house to go over the certification updates and applications and make comments or ask questions for Eric [Sideman] to follow up on.” Johnston founded Johnny’s Selected Seeds, and the company’s research farm in Albion was certified organic by MOFGA in 1979. Colson continues, “Our committee members covered most of the state so we often knew the farms we were discussing.”

Sideman believes that the growth in the certification Kafka and Colson describe was based on two factors. The first was that the interest in certified organic food was blossoming. But there was a second, equally important, factor.

“I think that the idea of everyone understanding and following the ‘rules of the road’ played a part,” says Sideman. “Not only did we work to reduce the number of intentionally cheating folks, but we reduced the number of people who were using the word ‘organic’ when it was not legit simply because they didn’t know the rules. Also, part of my job was to explain what organic farming was and the principles behind it. I worked hard to get the idea across that the foundation was taking care of the soil, and that the standards required this. I worked to explain how the required practices lead to improved soil structure, increased soil biological activity, and conserving and recycling plant nutrients.”

Organic rules of the road in Maine developed in parallel with those across New England. Sideman met regularly with certification organizations in the region to harmonize standards across state borders. As harmonized standards evolved regionally, feathers were occasionally ruffled locally. Kafka recalls one instance.

“Early on there were some products we were fond of that no longer fell into the organic realm,” says Kafka. “There was a potting mix that we had been using that we had to stop using. When you get used to something you don’t want to change, but when you’re forced to change things often work out better.”

One of the major changes in MOFGA’s organic certification that took place in the late 1990s was the creation of standards for livestock. The standard writing was contentious, Sideman says, because they were being written at the same time that organic livestock production practices were being developed.

As the MOFGA membership adapted livestock standards they recognized the need for someone to work with farmers to transition to organically certified livestock. Eric had served the dual role as a MOFGA extension agent and an inspector. Diane Schivera was hired in 1998 to serve in a similar capacity with a focus on livestock and dairy. A separate livestock certification committee was also established at that time.

Schivera describes a set of certification standards that were in flux.

“When I was originally hired the young dairy stock didn’t have to get fed organic feed,” Schivera says. “The cows did and they could transition after a time but now they have to be on organic feed for a year. That was a big discussion at our growers’ meeting because it was more expensive for farmers to buy organic grain for the calves.”

Schivera and Sideman continued to work with regional and national certifying organizations to create seamless organic certification standards across the country. In 2002, the Organic Food Production Act went into effect and national standards were established. At this time, MOFGA Certification Services LLC (MCS) formed to provide USDA-accredited organic certification services to Maine farmers and food processors.

Paul Volckhausen, a diversified farmer at Happy Town Farm in Orland and past MOFGA board president, says there was hardly a bump in the road transitioning from the state to the federal standards.

“As a farmer I don’t think I saw much of a change from MOFGA to the National Organic Program,” says Volckhausen. “Some of the rules changed, like the inspectors could no longer give advice, but the process was still the same. But as a member of the certification committee, it changed our role completely. Instead of making the rules we could only interpret them.”

That work of interpreting the National Organic Program’s (NOP’s) rules via committees continues to this day, according to Chris Grigsby, who has been the director of MCS since 2016. Grigsby says that an advisory committee, broken down into subcommittees based on the NOP’s production categories, helps MCS staff come to an understanding of changes or proposed changes in the NOP.

“The advisory committee assists MCS staff with rule interpretations and development of policies based on those interpretations,” says Grigsby. “We activate them on an as needed [basis]. We also call upon them if there are rule changes proposed by NOP or NOSB that we are commenting on so as to gain firsthand perspective from industry or scientists.”

The committees are made up of certified farms and processors, scientists, academics, veterinarians and staff from MOFGA’s farmer programs team.

In addition to the advisory committee, MCS is governed by a management committee appointed by the MOFGA board to oversee the certification program, according to Grigsby.

The hard work of today’s members of the MCS management committee and the advisory committee, along with many others, is the glue that continues to hold together what Ken and Roberta Horn and many other visionaries began five decades ago.

About the author: Tim King is a produce and sheep farmer, a journalist and cofounder of a bilingual community newspaper. He lives near Long Prairie, Minnesota.