|

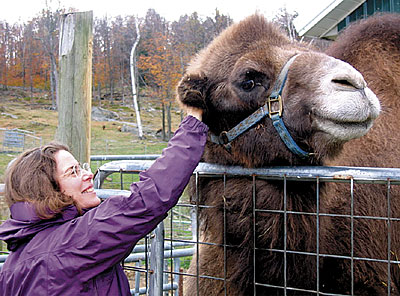

| Carol Spack and Bobby, the camel – in “person.” Photo courtesy of Carol Spack. |

By Holli Cederholm

Massachusetts-based artist Carol Spack started sculpting rare breeds of farm animals in a series of events she refers to as nothing short of serendipity. In fact, she didn’t even realize she was doing it. Initially, just following her curiosity about animals and small towns in midcoast Maine, Spack visited small farms and walked through forests and along the ocean.

“Nature is so beautiful that if you go out into the landscape – bird, flower, leaf – there is nothing we can do to improve on that. Yet, as artists, we want to reflect it,” says Spack.

Growing up in Framingham, a Boston suburb, Spack credits her time in the garden with her parents, and time playing in nearby woods with her keen delight in nature and reverence for animals that as a child she expressed in art work. But what really brought the influence of other animals’ awareness and the delight in smells, texture and patterns in nature were her childhood and adult relationships with family schnauzers.

|

|

| Bobby as a work in progress, at the foundry and as the final sculpture. Photos courtesy of Carol Spack. |

|

“I love, love, love dogs, and schnauzers are my favorite.” A dog breed whose name is derived from the German word for snout – schnauze – it seems appropriate that Spack would find, at the end of her terrier’s nose, a new way to experience nature, and a lens in which to view her sculpture. “I would watch HB [her dog] smell the tip of a single leaf, and that taught me a much higher level of awareness,” says Spack. “What else do humans miss by passing by too quickly, or simply not taking the time to look at what is in plain sight? It makes sense to pause, listen, and look again.”

While perusing a bookstore in Maine, Spack noticed a bookmark advertising Kelmscott Farm in Lincolnville. But what really caught her attention was the printed imagery on the bookmark featuring wooly sheep and a bristly spotted pig. At the time, she didn’t even know the significance of the particular breed of swine represented here: Gloucestershire Old Spots. This breed originated in England in the mid-1800s and is now considered in decline by the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC).

Barnyard-themed inspiration next struck from the pages of the Wall Street Journal: A black and white line drawing of a shaggy donkey captivated Spack enough for her to search out a living example, a Baudet du Poitou (Poitou donkey) named Norman, whom she found on the Hamilton Rare Breeds Foundation Farm in Hartland, Vermont.

When a third animal muse appeared in yet another unlikely place – this time a baby Bactrian camel cited in a Tufts Veterinary School report – and Spack scheduled a follow-up trip to Tregellys Fiber Farm in Hawley, Mass., the pieces started to come together for her. “I realized an entire movement existed to protect old breed farm animals,” she says.

Many of these varieties lost appeal when livestock and poultry breeders selected for more commercially desirable traits – such as a disposition for rapid weight gain or increased milk production. In the case of breeds once prized as draft animals, such as the Poitou donkey, their numbers declined greatly with the advance of automotive and tractor technology. “This series of farm visits cemented my interest in rare breed farm animals,” says Spack. She joined MOFGA in 2008 and headed to the Common Ground Country Fair hoping to see more. Through her work, Spack is helping others experience these animals, therefore inadvertently becoming a part of the conservation effort.

Touchstone Animals

Unlike the ALBC or Hamilton Rare Breeds Farm, Spack was not proposing to educate her audience about endangered livestock breeds. “Art should speak for itself,” says Spack. And hers does. Aside from a nominal descriptor, such as “Je Suis un Baudet de Poitou” or the more ambiguous “Girl Calf,” her animal sculptures stand upon their aesthetics rather than words. This allows viewers to interpret her art in the same way that Spack tries to interpret her subjects: with fresh eyes, and without preconceived notions.

Spack hopes that her audience will touch her work and, in turn, will be touched by it. Hence, she often refers to her sculpture as a “touchstone.” And the Poitou donkey, defined by its large, floppy ears and long, soft jacket, does invite tactile experience. “If people touch Norman the donkey and feel his coat and wonderful ears, maybe they will see there is great beauty at hand. With touching my sculpture, [people] become aware just how wonderful another creature is. They’re not just an object.”

In working from live models, Spack is not only able to capture distinct ruffles of wool that might be missed in sculpting from a photograph, but she is also able to capture what she refers to as a “characteristic gesture.” For instance, a sculpture of Patrick, a Gloucestershire Old Spots pig asleep, sprawling on his side, doesn’t need a bronze mud pit to complete the scene; the action itself is inherently familiar to the iconic barnyard. “I try to develop a sense of who they [the animals] really are,” says Spack.

|

| Patrick sleeping. Carol Spack photo. |

From Farm to Finish

With each of her livestock sculptures, Spack has followed a similar process – starting on the farm. After locating a live model, Spack spends two to three weeks in the field, or as she describes it, “in a paddock on top of a bucket.” The first few days are spent sketching, and the next few making a wire armature, which is basically a wire skeleton. She often makes multiple wire sketches, as was the case with Norman. “For the donkey, I made a horse first, before I understood the unique characteristics of a donkey,” says Spack.

When the armature is completed, Spack mounts it to a baseboard and covers the skeleton with an oil-based clay. She is then ready to move on to the next phase of her creation process – a five-step, several-month procedure referred to as “lost-wax casting” that takes her to a bronze foundry to complete and results in a bronze sculpture.

|

| Norman, a Poitou donkey. Carol Spack photo. |

This involves making different molds, including a flexible rubber mold of the clay, a wax casting, and a stiff ceramic investment that receives the molten bronze. Spack then does rough finishing with air power tools and takes up finer hand tools to chase the final surface details before applying the patina for color.

“Bronze is a wonderful material that can express the texture, form and spirit of my animal subject, wild or gentle, sumptuously wooly or refined, delicate or powerful,” says Spack.

The bronze sculptures are small enough to hold or to display on a table – which Spack intended. She hopes that their smaller size will make them more accessible to everyone, perhaps spreading her own growing interest in maintaining rare breeds. “I am proud to contribute to such work.”

For information about Carol Spack and her work, visit www.spackart.com.

Some farms and organizations that support rare breeds of animals are:

American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, North Carolina – www.albc-usa.org

Aldermere Farm, Rockport, Maine – www.aldermere.org

Ayrshire Farm, Upperville, Virginia – www.ayrshirefarm.com

Hamilton Rare Breeds Foundation Farm, Vermont – www.hamiltonrarebreeds.org

Kelmscott Rare Breeds Foundation, Maine – www.kelmscottfarm.com (Now closed, but the Web site has a long list of other farms with rare breeds)

Tregellys Fiber Farm, Hawley, Mass. – www.tregellysfarm.com

Wolfes Neck Farm, Freeport, Maine – www.wolfesneckfarm.org