|

| Michael (and Grace) Phillips (center, on bench) discuss apples after lunch at Francis Fenton’s farm. This was the last of five orcharding classes offered by MOFGA last summer. Photo by Russell Libby. |

|

| John Bunker talks apples. Photo by Russell Libby. |

By Russell Libby

MOFGA’s 2004 Organic Orcharding series concluded with a visit to Francis Fenton’s Sandy River Orchard in Mercer, Maine, on Saturday, October 9, 2004. Sandy River Orchard is known for its diverse collection of varieties, featuring a number of apples Fenton has collected from old family orchards around Franklin and Somerset counties over more than 30 years. John Bunker from FEDCO Trees and Michael Phillips, author of The Apple Grower, also presented.

Fenton returned to the orchard in 1972, after retiring from the Navy. His grandfather fought in the Civil War. His father, born in 1860, planted many of the original trees in 1904. If you get the idea that Fenton has been at this for a while, you’re right: He’s 89! He doesn’t climb the ladder so much now, but he attributes his good health to a diet of applesauce (from ‘Wealthy’ apples) three times a day, and the continuing physical exercise of managing about 3 acres of trees.

Learning Varieties

Bunker talked about how he “learns varieties,” using one of Fenton’s ‘Wealthy’ apples as an example. Each apple has a distinctive shape, color, basin (bottom of apple) size, taste and texture. For Bunker, much of the learning is based on getting the right image of “red” into his mind. When he’s trying to get a variety into his head, he’ll line it up on a shelf in his kitchen and observe it until he gets a clear picture. Those pictures help him identify apples in orchards where names of trees are no longer known. Some varieties have distinctive tree shapes and branching characteristics, which helps in the field, but an apple on a table doesn’t give those clues.

Sandy River Orchard

Fenton doesn’t manage Sandy River as an organic orchard. He focuses a great deal on having a variety of apples to supply his neighbors, on making good, rich cider by mixing many varieties, and on knowing the people who come to the farm. He’ll try new ideas (mason bees for pollination, many different rootstocks), but he has really focused through the years on trying many different varieties and searching for the best of what’s left in the region’s many abandoned orchards.

‘Wealthy’ is his favorite, and he grows them large by thinning – by hand on lower branches and by shaking for higher branches. Usually peak harvest is about September 15, but this year the apples held well later. Fenton eats them and makes pies, but especially enjoys applesauce. He has a full range of the traditional local apples (‘McIntosh,’ ‘Macoun,’ ‘Empire,’ ‘Rome,’ ‘Northern Spy,’ ‘Baldwin’) but also has dozens of less well-known varieties. I sampled ‘Twenty Ounce,’ ‘Pound Sweet,’ ‘Haralson,’ ‘Cox’ Orange Pippin,’ ‘Spencer,’ ‘Winter Banana’ and ‘Fallawater.’

|

| Francis Fenton, age 89, attributes his good health to a diet including ‘Wealthy’ applesauce and to the physical exercise of managing about 3 acres of trees. Photo by Russell Libby. |

For Fenton, keys to success have been pruning the orchard above deer browsing range and keeping the trees open. He prunes to the trees’ growing style, not to a predetermined shape, but always works to bring light into the trees.

When to pick? When the apples taste good to you. Fenton tends to wait, and doesn’t worry about drops as much as an organic orchardist might. When the apples taste right, he picks.

The orchard is open most days during the fall, catch as catch can, on the West Sandy River Road in Mercer.

Varietal Issues and Fall Orchard Care

Phillips reminded us that choice of varieties is a big part of planning for organic orchardists, but it’s not the only element. Ultimately genetics alone won’t solve the problems of growing an apple tree in one place for decades (or, in Fenton’s case, for a century or more; one original tree is about 150 years old).

A few varieties, such as ‘Arkansas Black’ and ‘Redfree,’ seem to have some resistance to curculio, likely due to their hard skin.

Almost all breeding for disease resistance in the United States traces back to an apple identified in Illinois in 1905-1907, and used as the basis for breeding starting in about 1947. The Purdue/Rutgers/Illinois (PRI) Cooperative has developed many scab-resistant varieties (‘Prima,’ ‘Priscilla,’ ‘Pristine,’ ‘Goldrush,’ ‘Dayton’), and all of these share the “VF” gene with the original Illinois tree, as do the Cornell breeds ‘Liberty’ and ‘Freedom.’ This gene basically makes each cell of the apple hypersensitive to scab. When the cell is exposed to a scab spore, it dies, leaving the spore no energy to spread to adjacent cells. Since scab races evolve over time, they may eventually overcome the resistance of the VF gene.

Why are some old cultivars resistant? They may have some genetic resistance; they may also be growing where a good mix of mycorrhizae, fungi and bacteria in the soil favor tree growth.

Some of Phillips’ variety choices are ‘Williams Pride,’ ‘Redfree,’ ‘Dayton,’ ‘Milton,’ ‘Goldrush’ – if you have the heat to ripen it, ‘Duchess,’ ‘Red Gravenstein,’ ‘Macoun,’ ‘Spartan,’ ‘Sweet 16’ – a current favorite, ‘Burgundy,’ ‘Senshu’ – from Japan, ‘Bramling’s Seedling’ for cider, ‘Russets’ and ‘Baldwin.’

Phillips emphasizes building soil health through haphazard mulching, with raspberry canes, brush, wood chips, compost. He even encourages us to find trees that are growing very well and inoculate orchard trees, or wood chip piles to become compost, with soil from under the healthy trees. Using this approach, we can be like Fenton and plant anything wherever we want.

Since 60 to 70% of on-farm apple sales are in September and October, when people are thinking about apples, having a good mix available then is important, including some that make good early cider. (Early cider is improved by adding some pears to the mix.)

|

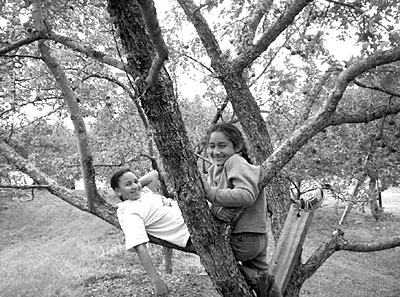

| Rosa Libby and Grace Phillips demonstrate the second-best reason to grow apple trees. Photo by Russell Libby. |

Fall Care

Don’t leave borers in trees all winter: Check every tree in the fall. Phillips uses pea stone mulch, pulling it back to check for borers, then replacing it around the trunk. He also coats trees with kaolin clay (pottery variety) as a paste so that he can see what’s happening on the tree trunk.

Scrape back dead bark, which is where codling moths overwinter.

Remove drops at your final picking to help cut deer pressure for the winter and insect and disease pressure next year – especially scab. As another scab control, Phillips sprinkles two quarts of lime per tree on the leaf litter when half the leaves are down, then mows the orchard with a flail mower; this achieves a 50 to 90% reduction in spore numbers. Then he applies a thin layer of compost.

To control deer, Phillips runs an eight-wire fence, 6 feet high. He adds peanut butter on aluminum strips around early October to remind the deer (when they taste the peanut butter and get zapped) that the fence is electrified. He likes Fenton’s approach, as well, for a standard tree orchard: Fenton wraps trees in floating row cover in the fall, pinned with clothespins, to keep deer away.

Everything should be cleaned up in the fall: branch spreaders, maggot traps and fly balls, pruning debris. (By the way, next year Entrust lures should be available and ok for organic pest control.)

The event concluded with everyone picking some favorite apples to take home, and relaxing a little!