|

| The North Branch family, left to right: Ada, Anna, Seth, Elwyn, Tyler and Misha |

|

| Some of the horse-drawn equipment used on the farm, with the fenced (from deer) fruit tree and shrub nursery in the background. |

|

| A closer look at the irrigated nursery |

|

| North Branch specializes in vegetable crops grown for its winter CSA |

|

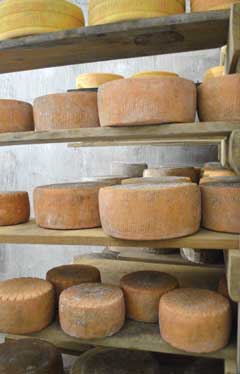

| Seth shows the cheese cave to a group of visitors. |

|

| Tyler explains the construction and functioning of the cheese cave. |

|

| North Branch makes hard and semi-hard artisanal cheeses. |

|

| The new vegetable processing/storage and creamery building has streamlined much of the work at North Branch Farm. |

By Jean English

Photos by the author

Two-year-old Elwyn soars on an indoor swing pushed by his mother, while 6-year-old Ada sits on her Uncle Tyler’s lap. Now Ada “flies” around the room wearing a blanket cape fashioned by Tyler’s partner, Misha, who is clad in a matching cape. Then Elwyn nurses while his parents, Seth and Anna, and his uncle talk about their farm. This flurry of activity and support of family members is all part of the plan.

The plan revolves around North Branch Farm – 330 acres of fields and woods in Monroe, Maine, just a few miles from the family homestead on Stovepipe Alley where brothers Seth and Tyler Yentes grew up. With two other siblings and their parents, they produced and preserved much of their food. That’s also where Tyler, at age 16, bought his first team of draft ponies, and where the brothers decided they wanted to farm together.

Their homeschooling included music along with their “classroom” work. Tyler studied violin with Janet Ciano, Clorinda Noyes and Gilda Joffe and then taught himself traditional fiddle music. Seth studied cello with Ciano, Dick Noyes, Miles Jordan of the DaPonte String Quartet – “a great instrumental teacher” – and at the University of Maine Orono with Noreen Silver. He transferred to Indiana University for one semester to study with Emilio Colón – “and then,” he says, “decided I wanted to be a farmer rather than spend so much money on a college education that was going to lead me to a city. So I moved home!” Indiana, ironically, was part of his farming heritage: His mother grew up there and his great grandparents farmed there.

Their musical expertise has led to some off-farm income through Seth and Tyler’s fiddle-cello duo, Whiffletree. Tyler also teaches classical violin and fiddle, and Seth, cello. Now, though, with two young children, Seth is minimizing his musical engagements.

Anna Shapley-Quinn, the daughter of two family physicians, grew up in North Carolina, where her family ate “in a counter-cultural way.” She became interested in agriculture – especially after learning in a high school class about the environmental effects of conventional farming. “I thought, maybe this is something I could do for a living that would let me be outside.” She wasn’t sure she could make farming work, though, and her parents wanted her to go to college, “so I decided to go to Hampshire College because they have a 15-acre vegetable farm and I could study writing and anything else I wanted.”

Anna visited Maine with two of her Hampshire roommates who were from Deer Isle and had grown up playing chess against, and music with, Seth and Tyler. After college Anna planned to spend one summer in Brooksville helping those friends start the bakery Tinder Hearth and then return to North Carolina to farm. But Seth and Tyler were at the first contra-dance she went to in Maine that summer … “and here I am!” she says. She also worked at Four Season Farm between college semesters in January 2006 and again in the summer of 2008 while at Tinder Hearth.

Tyler’s partner, Misha Vargas, is relatively new to North Branch. She worked for the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Puerto Rico and transferred to the Bangor office when a job opened there.

Buying and Building the Farm

Seth, Anna and Tyler bought their farm in 2009 – two years after the brothers had met the elderly couple who owned what was then Guernsey Knoll Farm and started negotiating to buy the farm. Seth, 24 then, and Tyler, 20, decided to forego college and use funds their family had saved for tuition to help buy the farm. Other financing came from the Anna and the brothers’ families. They moved in and changed the name to North Branch Farm, after the north branch of Marsh Stream, which runs along the property.

They renovated the barn, built Seth and Anna’s house (Tyler and Misha live in the house that was already on the farm) and started improving the fields for organic vegetable crops, planting orchards and a nursery, growing hay and raising grass-fed meat and milk. Their home landscape includes peaches, pears, apples, apricots, juneberries, medlars, cherries and more.

Also in 2009 Tyler acquired a team of Percherons (now one Percheron and one Haflinger). Most work on the farm is done with horse and hand power, and some with tractor power. In addition, solar panels on the barn provide the energy used in the houses, barn and vegetable processing/packing/storage building.

“We’re really concerned about climate change and figuring out how we can use our farm to sequester carbon and minimize our impact,” says Seth.

Soil Building

North Branch rotates crops with cover crops and fertilizes the vegetable fields with composted manure from the farm animals. They occasionally buy in a little fish or blood meal from Organic Growers Supply to topdress vegetables. “Mostly we try to do intensive grazing and pasture management,” says Seth, “coupled with using compost and bedding.”

They mulch highbush blueberries, orchard trees and edible landscape plants with wood chips every other year. “It’s not a lot of fertility,” says Seth, “but it’s building the ecology of the soil and making an environment that’s more conducive to those woody plants’ success.” (When they planted the blueberries, they added some blood meal, granite meal and sulfur to the soil.)

The chips have come from various local sources. The farmers hope to make their own this season … although making enough for 800 blueberry plants and 500 fruit trees plus the many landscape plants is a challenge.

Their vegetable and blueberry soils are very sandy, while others have more clay. Seth says they’re excited to be trying biochar as a soil amendment, especially for the sandy soils. They’re welding together a charcoal retort (a system to make charcoal in a cleaner way than in an open or smoldering pit), and they plan to use slab wood from their Wood-Mizer sawmill to make charcoal. They’ll mix the resulting biochar into the manure and compost “and hopefully hold on to the fertility longer in our soils” and sequester carbon for a long time. If the retort system works, they’ll try to use it to heat water to heat their seedling greenhouse as well. They don’t envision problems with raising the soil pH too much with biochar since they have so much acreage.

“It’s a big experiment,” says Seth. “Compost is a great thing,” but finding enough compostable material for their acreage is difficult. And even with lots of cover cropping, their sandy soils lose organic matter when they plow in a cover crop. In addition to adding compost and biochar, they hope to plow less by cover cropping longer … at the risk of having more weeds.

Biological activity increases as soils get warmer, Seth notes, so biochar, which helped make some fertile soils in the Amazon, may help their soils as well – especially as the climate warms. They also wonder if ramial wood chips might help build organic matter, even in their vegetable soil.

The Nursery

At age 13 Seth learned to graft apple trees from his stepfather, Jonathan Fulford, and he developed a passion for growing fruit. He then planted and fenced a 3-acre orchard at the family homestead and began growing grafted fruit trees for Fedco Trees. The North Branch farmers now grow an acre of nursery stock for sale, primarily to Fedco, as well as about 240 trees for the Waldo County Soil and Water Conservation District. The stock includes apple, pear, plum, cherry, Cornelian cherry and peach trees; grape vines; lowbush bueberries; highbush cranberries; medlars and elderberries. All live in the nursery for two years, with half an acre being dug each year.

They dig nursery stock with an 80 hp, four-wheel-drive tractor with a side-mounted bed lifter (because the trees are so tall) – “a big J-shaped chunk of iron that cuts under the roots of trees and loosens the soil,” Seth explains. They loosen and dig one row at a time. The same implement lifts carrots and parsnips as well, two rows at a time.

Each August Seth shares his skill by teaching a bud grafting workshop at North Branch Farm as part of MOFGA’s organic orcharding series.

Vegetables

On their 4 acres of MOFGA-certified organic vegetables, they grow winter greens and storage crops for sale through their 18-week (nine biweekly pickups), 55-family (so far) winter CSA (mid-October through mid-February) – a schedule that works well with their busy summers of tending nursery crops and fruit, milking, and making hay. “We don’t have to pack, market and distribute vegetables in the summer,” says Seth.

In 2016 they tried a free-choice CSA model: Customers packed their own boxes from what was available, in quantities and combinations they liked, within a 20-pound weight limit for a full share and 10 pounds for a half share. People seemed pretty satisfied with the system, says Anna.

They also sell in the farmers’ market at the Common Ground Country Fair, to a few area restaurants, to natural food stores and co-ops and at The Winter Market in Blue Hill.

Their new veggie/creamery building with cold storage rooms, washing and packing areas has vastly improved their operation. A wood boiler heats the building, the cheese vat and the water.

“It’s awesome,” says Tyler. “Everything’s much more efficient.”

“When we bring vegetables in for storage,” says Seth, “we do them in pallet bins. We build walls on a pallet and then we can move them around. It takes up less space than boxes or bags.” The 4-foot-wide doors enable them to pull a pallet through the pack area and into the cooler.

In April, “We’re still selling carrots that we’ve done nothing to,” adds Tyler. In the past, with less than ideal storage, they had to trim the tops and had roots growing from the carrots by January. Now, with a constant 33 F temperature in the 24 x 22 refrigerated space, their carrots were still great even into April.

Blueberries and Tree Fruit

Their acre of highbush blueberries – Duke, Blue Jay, Blue Ray, Jersey, Nelson and Meader – opened for pick-your-own in 2016. (They dug out 100 Elliott plants that matured too late.)

They sold about 1,000 pounds of blueberries last summer, opening for a couple of days each week. “It’s a fun way to get people here and have folks get to know our farm,” says Seth, “particularly a lot of locals who drive by but don’t see a lot of what’s going on.”

At the end of the season, they lost about 15 to 20 percent of the crop to the spotted wing drosophila, a new fruit fly pest in Maine. “Last year was really our first year of production,” says Tyler. “We’re at maybe 10 to 20 percent of what we’ll be getting in a few years. [The pest] may make a bigger difference then.”

They had some limited turkey pressure but managed to chase the flock away, and songbirds weren’t a problem even without netting. “It’s something we’ll monitor,” says Seth, adding that Maine fruit grower John Meader thinks bird migration patterns have changed, so costly netting may not be necessary now.

As the blueberries produce more, the farmers will have to find more markets, says Anna. And parking, adds Seth. They’re up against the lowbush blueberry market, he adds, “but a lot of people love the fruit, they love the size, they love being able to pick them. So I think as our reputation builds and people get to know us, we’ll be able to keep up with the supply.”

“And we made an effort to get varieties that will actually ripen fully here,” says Anna. “A lot of people have the perception that highbush blueberries aren’t as sweet or good as lowbush, but we’ve labeled varieties, and as we get people out there, we show them what’s actually ripe.” The harvest season runs from the last week of July through the first week of September (when the fruit fly was becoming active last year).

They prune out the few canes exhibiting witch’s broom, a rust fungus with balsam fir as its alternate host. They considered cutting down nearby firs but learned that the disease occurs in blueberries even when no firs are within sight.

The Cows and the Creamery (and a Few Chickens)

North Branch has been a licensed dairy since 2011 and a licensed creamery since 2015. It is a seasonal operation, milking from May through November when the cows are on fresh pasture, and making artisanal hard and semi-hard, cave-aged, unpasteurized cheeses then. They have 34 cows and are milking nine in a mixed herd of grass-fed American Milking Devon crosses, Canadians and Jerseys. Tyler says he switched from purebred American Milking Devons because their production was too low.

After years of bottle-feeding calves twice a day, they now use a kiwi calf feeding system – a rubber nipple attached to a tube that goes into a barrel of milk. The calves drink more, with their heads at an angle that moves milk into their milk stomach instead of their grass stomach. Sometimes the farmers add whey, a byproduct of their cheesemaking, to the milk, but the calves like whey only when it’s really fresh, says Tyler.

The animals at North Branch are not certified organic because the farmers are not always able to buy in certified animals due to lack of availability. They also buy some hay from a local farm that isn’t sprayed but isn’t certified. All North Branch hayfields and pastures are certified organic, and the grain they buy for the 20 layers and 50 meat birds they raise for themselves is organic. (The meat birds move around a pasture in two chicken tractors, while the layers free-range on pasture after cows have been moved off.)

In 2014 they built a cheese cave. After excavating into a hill, they poured concrete into forms they had spent weeks constructing, later removing the forms. From the surface of the 5 feet of soil on top of the cave to the base measures 17 feet. They got their construction skills and advice from stepfather Jonathan and stepbrother Gilbert Fulford of Artisan Builders, and then from hands-on experience on the farm.

Learning and Growing

“We grew up on a farm,” says Seth, “but we didn’t know anything about packing, marketing, using a plow or tractor – we used a garden fork and a wheelbarrow – so we learned by trial and error and talking to other farmers. That left a lot of room for error but also a lot of room for innovation, so we have a very different crop plan than most farms. Being involved with Fedco has certainly been a huge part of that – building our nursery to where it is has really influenced how our farm operates.”

The nursery is now the largest income producer, and it has been growing every year, easily tripling since they moved there. Its growth is now slowing to about 15,000 trees per year.

Vegetables are the second greatest source of income so far – although they take more labor than the nursery.

“The cheese will definitely be growing for three to four years,” Tyler adds, while the blueberry and orchard operations are still in the growth stage.

Asked if they have some end goal, Tyler responds, “We’re farmers, and farmers are always trying new things.” Anna says, “I like the idea of refining the operation that we have at the scale where we are, rather than expanding, but we all negotiate and compromise.”

After pondering, Tyler adds, “Humans, and farmers, seem to always be curiously observing and innovating, and we like that. At the same time, our current economic system, i.e. capitalism, has been driving constant growth and expansion, and this needs to be questioned for the ways in which it forces farmers to prioritize blemish-free products and high yields over ecosystem health (better among organic farms) and human community health.”

Asked about advice for incoming farmers, Seth says, “Figure out if you can till as little as possible. We came from a home garden scale. Jumping into horse work, we found we could farm acres with just a few people and produce a huge amount of food. But we found out the long-term effect of plowing, at least on our sandy soil, is detrimental.”

They’re still learning to balance farming and family, says Anna. They try to follow the advice of others to have more people around, more support, and not to operate in a bubble and feel that they have to accomplish everything on their own. Having CSA members come for work parties and exchange work for shares has been a big boost for morale, she says. They have an employee, Graham Mallory, who also raises livestock with his wife, Emily, at Pastures of Plenty in Jackson. This year they also hired Vince Vercillo to make cheese three days per week and to help on other parts of the farm two days per week. They’re figuring out whether to have more employees, and they dropped their Bangor and Ellsworth CSAs.

The farm includes about 200 acres of forest – about 70 of those under an NRCS timber stand improvement plan, with Mallory doing that improvement on a contract basis.

A final piece of advice: “Don’t be afraid to plant a few fruit trees!” says Seth. “The years will go by whether you plant a few fruit trees or not, and it will be so rewarding to get that fruit from your land.”