|

| Edwina and Steve Hardy, though “retired,” keep busy with their maple sugaring operation. Jane Lamb photo. |

By Jane Lamb

Steve Hardy figures he began “sugaring” – as it’s called in his native Vermont; in Maine they call it “sapping” – when he was about eight years old. His mother told him he’d have to wait until the quart jar on the tree on the front lawn was half full before he could bring it in to boil down on the kitchen stove. “I got almost enough syrup to taste,” he recalls, chuckling at the memory.

When he was a teenager, he helped a farmer haul buckets of sap to his sugarhouse with horse and sled. But not until 10 or 12 years ago, when he started thinking about retiring, did Steve realized what he really wanted to do: make maple sugar. “It shortens the winter,” he says. “It’s winter when you start, and spring is there when you get done. You’re busy doing something that’s fun and it’s good outdoor work. Last winter there were 3 or 4 feet of snow when we started to sap. We had to shovel out the main lines. When we finished we were walking through wildflowers – spring beauties, trillium, trout lilies, hobble bush. We’re constantly reminded that hobble bush is well-named. We’re always tripping over it!”

Looking ahead to retirement from 30 years in production and supervision at the Boise Cascade Mill in Rumford, Steve began doing what many others do in Maine. He “backyarded it.” He tapped 50 to 100 trees on a woodlot he owns in Peru and boiled the sap down on weekends on an outdoor fireplace at his home in South Rumford. He retired from Boise Cascade four years ago. In 1994, he started building a sugarhouse on Spruce Mountain in Andover C Surplus township, and Mountain Maple, a MOFGA-Certified maple syrup operation, was born. “We didn’t know what to call it,” says his wife, Edwina, his partner in the business. “Maple syrup from Spruce Mountain didn’t make much sense, and ‘Surplus Syrup’ was even worse.” They settled for Mountain Maple.

|

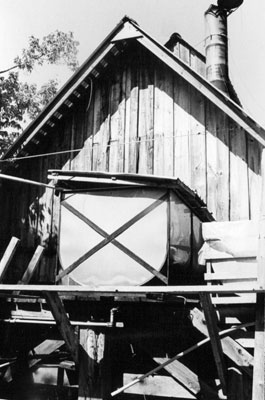

| Mountain Maple’s sugar house on Spruce Mountain. Jane Lamb photo. |

Green All the Way

Surplus C is wild land owned by the Pingree Estate and managed by Seven Islands Land Company, which is Green Certified. Steve and Edwina lease the land from Seven Islands for so much per tap. Compared with the McPhee operations on the Golden Road, 20 to 30 thousand taps, Mountain Maple, with its 2,000 taps, is a mom and pop operation. The maple grove is on the mountainside, 100 feet above the sugar house. Ten miles of sap line connect the taps to one-inch mainline pipe, two miles of it, that carries the sap downhill to the 700-gallon storage tank at the back of the sugar house. When Steve approached Seven Islands, the company had several maple areas that needed to be thinned. The one on Spruce Mountain was last cut in 1937, the year Steve was born. Although he isn’t a Registered forester, he got a bachelor’s degree in forestry and a master’s in pulp and paper production from the University of Maine in the 1950s. He continues his lifelong involvement with the woods, working these days with registered forester Mac McLean to develop management plans for private woodlots and land in tree growth. “To keep land in tree growth, which is a tax breakup have to have a management plan. You can’t just sit on it. You have to cut it,” he points out.

“When Seven Islands foresters cruised the Spruce Mountain Sugar bush, Steve went along. “I wondered if they would want the same thing I would,” he says. “They went through with a marking gun and they chose the same trees I would have.” He goes on to explain that the typical tree density in second growth forest is 125 square feet of basal area to the acre. Though maples are shade tolerant, this would amount to a lot of slender trees competing for sunlight.

|

|

| A sap line moves the product down the mountainside. Jane Lamb photo. | The maple sap holding tank. Jane Lamb photo. |

“For maple syrup, you want a big crown,” Steve says. “The leaves manufacture the sugar. The ideal for production is trees along a stone wall on an old farm to get the most and sweetest sap.” The grove needed to be thinned to 80 square feet of basal area per acre. (Basal area refers to the amount of square feet of tree 4-1/2 feet above the ground, translating round tree into square feet by mathematical magic.) At 80 square feet, an acre would contain a lot of trees that are 15 to 16 inches in diameter plus a few 20- to 25-inch old sentinels. Many of these, which are approaching old age, Steve doesn’t tap, preferring to let them live a little longer. Before he began sugaring, Seven Islands loggers thinned the forest. It takes the trees, once liberated from heavy shade, three or four years to develop a full crown to attain the best sap production.

Requirements for MOFGA certification state: “… no trees smaller than 10″ in diameter may be tapped. Trees between 10 and 12 inches may be tapped only if the health of the tree, its environment and the condition of the crown can support quick healing of tap holes … [n]o more than one additional tap for each additional 6-inches of tree diameter.” Steve is pleased to report that when it came time to be certified, Mountain Maple exceeded MOFGA’s requirements. He likes to tap trees that are at least 15 inches in diameter.

Steve built the sugar house from logs cut on his own woodlot in Peru and had them sawn by a local sawmill operator into hemlock posts, fir rafters and pine siding. “Every pine tree we cut was infected with blister rust and would be dead in three years, but it was still useful,” he says, pointing out the importance of well-managed timber harvesting. He designed the 22′ by 32′ building, which has a full- pitch metal roof and plenty of room for wood storage. For boiling the sap, Steve burns softwood slabs, birch slabs from a local dowel mill, round wood cut in his Peru woodlot improvement work and trash wood such as limbs and saplings. Junk wood produces a hotter fire than good stove wood, he says. He uses 20 to 25 cords per season. “It depends on how the sap is running. If it’s a good run, the whole process is more efficient.”

Making Syrup

|

| The evaporator. Jane Lamb photo. |

|

| Steve inspects next winter’s wood supply. Jane Lamb photo. |

With the sugaring operation 30 miles into the mountains from their Home in South Rumford, the Hardys had to work out a schedule for boiling down the sap. They try to start in the middle of the day, after the sap has had a chance run. “I never know how the sap is running,” Steve says. “You’d think I’d have some idea after all this time, but it’s 30 miles away. Sometimes I think for sure it’s going to run and it doesn’t. Other times I say maybe not, but I probably ought to go up anyway, and the tank is full.” When he gets there, if the sap is running, the tank will be half full or even almost full, hopefully not running over. “I start the fire and start boiling. Later on in the afternoon as the day cools, the sap will stop. We like to empty the tank that day, usually about dark. If we time it right, we’re done for the day. We have a generator, electric lights, flashlights and lanterns and we sometimes boil into the night, but not often.”

Both the Mountain Maple evaporator (5′ x 14′) and the storage tank are stainless steel with TIG welded seams, meeting MOFGA and Maine Department of Agriculture standards for 100% pure maple syrup. Lead in maple syrup is a serious concern. “Maple syrup is a pure, natural product. Even the suggestion of lead is awful,” Steve says. “The old evaporators were steel coated with English tin and soldered with lead solder and that was okay. Now the corrosive cleaners being used dissolve the lead oxide that has coated the seams all these years. Just 300 parts per billion is a dangerous amount of lead. Tests were showing 500 to 600 parts per billion.” When Steve first boiled in the spring of 1994, his syrup had to be tested for lead. MOFGA regulations further prohibit the use of synthetic fungicides, germicides, and fumigants for cleaning sap lines and equipment, synthetic defoaming agents during boiling, and filtering materials that release toxic substances or contain asbestos. Boiling sap produces a high head of foam, which can be controlled by using natural agents – milk, butter or olive oil.

A good day’s collection of sap, 700-plus gallons, boils down to about 20 gallons of syrup at the end of the day, Steve and Edwina haul it down the mountain in 35-gallon drums and 5-gallon jugs. Their F-150 Ford pickup, the most popular model of truck in the country, is actually owned by Jake, their beloved part-husky dog, who goes everywhere with them. “At least he thinks he owns it,” Steve says. They bottle the syrup at home, according to MOFGA and Maine handling and sanitation requirements, in decorated jugs, from half-pints to gallons. In a good season, they have made over 200 gallons between early March and mid- to late April. Last year (2001), with its peculiar winter, the volume was down to 175 gallons, even with more taps than in previous years.

|

|

| Steve checks the syrup with a hygrometer. Edwina Hardy photo. | Syrup is drawn from the tank. Edwina Hardy photo. |

|

|

| Steve pours syrup into a tank. Edwina Hardy photo. | Half-pint bottles are filled carefully with organic maple syrup. Edwina Hardy photo. |

The “Best Maple Syrup Known to Man”

The market for Mountain Maple Syrup is typical for a small, organic operation. They don’t advertise, but word gets around, and although they don’t have a sign out front, customers often come to the house. People are also finding them on their attractive website, designed by Edwina. They sell to a natural food store in Rumford, a grocery store in Hartland where Edwina grew up, the gift shop at the McLaughlin Garden in South Paris, to people who use it in making preserves, and to a number of B&Bs. “I think it’s normal for people who make ,aple syrup to have a variety of outlets,” Edwina says. The website is getting more and more attention. She is delighted with one of their more unusual customers, a man who works in Japan. “He found the website, but wrote us directly at our e-mail address. He wanted us to ship four gallons to friends in California where he was visiting. We were the first maple producers to respond to his request of information. He thought our web site was wonderful and said he was looking forward to many years of buying from us. He hadn’t been able to get any maple syrup to take back to Japan to share with friends and add a new item to the Japanese diet.”

Steve cites their product as a must for all B&Bs. “We think we make the best maple syrup known to man,” he boasts. “The second “B” is Breakfast. I can’t imagine a B&B worth its salt not serving maple syrup on their pancakes or not being fussy about it. You’d think they’d want really wonderful maple syrup. But I’m not in the B&B business.”

The Joys of Sugaring

Steve likes to be up at the sugarhouse any time of the year, day or night. Edwina goes up occasionally to help with the boiling, but prefers the daylight hours. “When it’s getting dark, I’m up there on the ridge,” Steve says, “thinking of Edwina wringing her hands, wondering why I’m not home. But I don’t mind the dark because I’m hearing the sap boiling and the wind howling. She gets kind of nervous when we’re boiling late and it’s drizzling a little bit and misty. She thinks it’s awfully spooky about midnight,” he teases. But Edwina enjoys the mountain just as much in her own way, as she writes in the Mountain Maple brochure: “Our workdays are enhanced by the sight of blankets of spring wildflowers …; the colors of fall foliage; in the winter by the breathtaking beauty of snow-covered trees and animal tracks in the snow; and in summer the green lushness of the woods and always the sounds of birds.

“We feel that it is the combination of location, traditional methods [boiling with wood] and the flora and fauna which gives our syrup its wonderful flavor.” She’s fond of saying, “You know spring has come when you hear the winter wren.” She remembers the time when they were boiling at dusk and a moose walked right up to the open door and almost walked in. “All kinds of things walk through that door,” she adds with a smile. “The people are all nice, but …”

It’s not as solitary on the mountain as one might think, says Steve. “When you see steam coming out of a sugarhouse, you’re supposed to stop and socialize, just walk in and say, ‘Hi! How ya doin.’ The standard conversation goes, ‘I wondered what was goin’ on here.’ You meet people who are active in the woods around here, hunting, fishing, antler hunting, snowmobiling. I have lots of visitors, really neighbors I haven’t met yet. They’ve driven by the sugarhouse a hundred times, and most days I’m not there, or when I am here, half the time I’m up in the woods. So when they see something happening, they like to stop and visit and I like them to.”

To those who think of the Maine woods as wilderness where no human activity should take place, Steve likes to point out that Mountain Maple is deep in the northern hardwood forest of sugar maple, yellow birch, beech, a little ash, a few red maples and an understory of shrubs like hobble bush and striped maple. “The animals hardly know we’re there.” He belongs to SWOAM, Small Woodlot Owners Association of Maine, which supports the active use of the forest through scientific management and wise harvesting. “Why don’t some of those [urban] environmentalists go up to Wytopitlock and say, ‘Gee guys, you make your living from the woods. Isn’t it awful!’ because the guys in Wytopitlock would say, ‘No, let me show you why it isn’t.”

Mountain Maple’s business address is 141 Hall Hill Road, Rumford, Maine 04276. Phone-207-364-8322; [email protected].

A Versatile Sweetener

Edwina points out that as well as on pancakes, maple syrup can be used in salad dressings, baked beans, homemade bread and almost any recipe that calls for a sweetener. She offers a simple recipe for a taste treat any child can make. Take a spoonful of peanut butter, pour some maple syrup over it, place it in a microwave for a minute or two (to soften the peanut butter) and put it on top of a dish of vanilla ice cream.