|

| Lisa Turner stands among her tomatoes in July. Lamb photo. |

By Jane Lamb

Like many another organic true believer, Lisa Turner was captivated by the prospect of year-round fresh veggies as promised in Eliot Coleman’s Four Season Gardening. “It’s a fabulous book for families,” she says. “If you want to have your own little greenhouse, follow what he says exactly and it works out wonderfully.” She put up a 50- x 17-foot greenhouse. “We ate all we wanted but there was so much left in March, I knew we couldn’t possibly eat it all, so I decided to sell some.” She got a cold reception at the first restaurant she tried. “Fine,” she told herself. “I’ll have a CSA [Community Supported Agriculture]. A friend said she’d love to buy vegetables, but she had a two-year-old and was entering her tenth month of pregnancy. She said I’d have to bring them to her. I said “Okay, I’ll deliver them.’” Thus was born another new niche in organic marketing.

Vegetables at Your Door

“That’s how I got started. I called a few other friends and started doing home delivery,” Lisa related as we sat inside the barn door on a blustery July day last summer, interrupted from time to time by young Will and Katy, insisting it wasn’t too cold to go swimming. We were wearing heavy sweaters. Eventually she relented and said they could go (to the campground across the road) until their teeth started chattering.

“I started selling vegetables in April [1996],” Lisa continued, laughing at the oddity of the timing. Lisa laughs a lot, which may account for her farm’s name, Laughing Stock, on the Wardtown Road in Freeport. In the following years she has added more greenhouses to extend the season on both ends, and more recently got into winter production.

Though the family has lived at Laughing Stock since 1984, Lisa didn’t start farming until five years ago, when her youngest was two. “I can’t imagine doing it with little kids,” she says. She’s been growing winter vegetables – mostly hardy greens – commercially for only two years. Her entire operation is MOFGA-certified, except for peonies, which she grows by the thousands for the cut flower market. “It took me a while to get into raising organically for commercial sale,” Lisa says. “It’s a whole lot easier to do it for yourself. You just pick out the bad spots and eat it. But [to sell], it has to be perfect. There’s a lot more effort fiddling with it.” She increased winter production by adding two more greenhouses last fall, bringing the total to five, two of them heated. She sells to The Portland Public Market, The Whole Grocer and Royal River Natural Foods in Freeport, as well as several restaurants. Her home delivery service is a warm-season operation.

|

| Reemay covers peppers and young corn, beside tougher crops in one of Lisa’s rolling fields. Lamb photo. |

A Speciality Marketing Niche

Lisa is delighted to have “invented” a niche that, as far as she knows, has no local counterparts. Her market, Portland’s rural “suburbia” of Freeport, Durham and Pownal, represents a different demography from the usual organic food clientele. “Home delivery gets organic produce to people who I don’t think would get it otherwise,” she surmises. “People whose schedules don’t permit going to a farmers’ market. They wouldn’t have time to drive out to a farm for CSA. CSAs think of shares, with people buying in quantity, to freeze and can the excess. These people don’t have time. They’re two-income families with kids for the most part. They don’t have time to go to a farmers’ market on Saturday. They’re too busy to go to a health food store because it’s an extra stop. I’m not sure they’d even walk across Shop ’n Save from conventional carrots to organic carrots.”

Unlike membership in a CSA, which requires a season’s commitment, Lisa’s customers can start the service any time they want and quit whenever they want. “I give them a list of everything I grow and they can check off what they never want to get. So if you have your own tomato plants or really hate rutabagas and radishes, you don’t have to get these. Then they tell me the total dollar amount to bring in reasonable quantities. Most want 10 or 15 dollars worth a week. They’re thrilled with getting all this fresh stuff that’s washed and crisp. I think they probably eat more vegetables than they used to.”

Lisa bills her customers once a month, so that they don’t have to leave money out or invest several hundred dollars at a time. Since her home delivery service is an adjunct to her sales to retailers and restaurants, she has no problem allowing customers to skip a week or two when they go on vacation. Some who go away for the summer are only on the list in the spring and fall. Of the 35 families to which she delivers, only one or two do this. “It doesn’t really matter if they don’t take their 10 dollars worth sometimes. Taken as a group, they’re my second largest client and they’re very important to me,” she says.

|

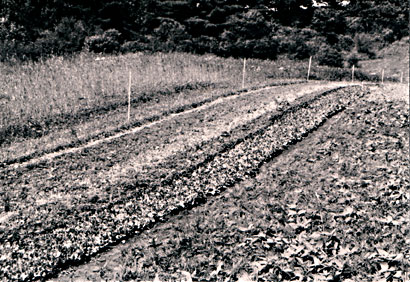

| Ribbons of greens in every shade supply a busy summer market. Lamb photo. |

Home delivery is a really good marketing strategy, Lisa told listeners to her talk at Common Ground Fair last September. “Farmers are afraid of it. They want people to come to them. They don’t like to deliver. But if I’m the one in the car, I get to decide how long we talk. If I were here, I’d still have to have three hours at least to be available for people to come pick stuff up. When I started, I thought of taking a two-, six-, and eight-year-old to a farmer’s market twice a week. It’s killing me now here. I couldn’t possibly stand that.”

Instead, she can throw them all in the back of the car and drive around for an hour and a half, once a week. “It’s good for me,” she says. “I’ve gotten to know people in my community that I never would have known otherwise. I have no time to be active in the community. It’s also good for organic agriculture,” Lisa points out, “because you’re making people aware that organic exists and they can be part of it.” Actually, she does this not only as part of her business, but as a member of the MOFGA Board and the Cumberland County Cooperative Extension Board, working to give more voice to organic farming, which surely qualifies as community service.

The Right Kind of Greenhouse

Lisa started out with two 17- X 50-foot Griffin greenhouses, one heated, the other not. But their rounded dome shape limited use of the space at the sides. She was always banging into the roof. Her third, 25 x 96, from Ed Person (Ledgewood Farm Greenhouse Frames, Moultonboro, NH 03254; 603-476-8820), has straighter sides and a gable-like roof design, which gives her the room she wants. She added two more of these, one heated, last fall, and will add two more this year. All the greenhouses have metal frames and are covered with a double plastic envelope, kept inflated with a blower fan. In the unheated greenhouses, she starts winter vegetables, mostly mesclun mixes, in late summer and fall. “You choose stuff frost won’t hurt, and use it fresh as long as you can.” She was cutting the last of it in November. “When you get back to 10 hours of daylight, it starts to grow again and you’re cutting stuff you grew in September. It’s semi-dormant. It doesn’t grow, doesn’t go bad – just like grass, only it tastes better!”

|

| Lisa harvests lettuce from an unheated greenhouse in December, where tomatoes grew in the summer. Lamb photo. |

Choosing what to plant in heated or unheated greenhouses is still in the trial and error stage for Lisa. “I have to see how it goes. There’s not a lot of literature on this, just a lot of figuring it out. Kale and arugula, which you’d think would be really hardy, will get a little tip burn when it gets really cold. Lettuce can take a certain amount of frost, then it gives up. It will hold at 30 degrees. My coldest last winter was 12 below, and it’s not much warmer than that inside [the unheated greenhouses].”

Lisa uses oil furnaces in the two heated greenhouses. “If you only heat to 30 degrees, you’re not using much oil, until when it gets to 10 below. Most of the time it’s at least 20 degrees at night and if it’s sunny, it’s hot in the day.” She doesn’t use fans for cooling. The Person models have roll-up sides; in the others she opens the doors at both ends. “I don’t worry in the winter. It doesn’t seem that necessary. In spring the plants can handle a little extra heat. It’s hard on the seedlings, because there’s only so much moisture in each little cell. The stuff in the ground has a lot more leeway.” Drip tape irrigation waters the rows in the greenhouses, which Lisa turns on “when I remember to.” She sprays the greens with a hose.

Seedlings and Flowers for Sale

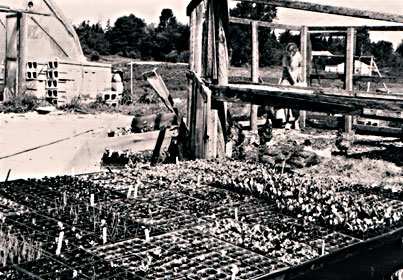

Lisa raises certified organic vegetable, flower and herb seedlings for sale at the farm and for her own business. She starts them all in one of the heated greenhouses, and pumps up the heat to keep them healthy. In April she moves the tomatoes into an unheated greenhouse where salad mix has been used up and the ground tilled. She had Sungold tomatoes ripe last July. All of the tomato varieties stay in the greenhouses for the whole season and last until the middle of October. Her summer, field-grown inventory expands to the full spectrum: more mesclun mix; lots of other greens on their own – endive, escarole, cress, dandelions, beet greens, chard; beets; peas; beans; summer and winter squash; root crops and brassicas.

|

| Some seedlings are sold; others restock empty rows. Lamb photo. |

Peonies are the only non-organic products at Laughing Stock Farm. “They get chemical fertilizer because they’re really expensive to get into. The start-up is costly and it’s three years before you can cut them. If you pick them right, they’ll keep for five days. Most people buy for big events, weddings, parties. They want them perfect for one day, and after that they don’t care. Peonies come at strawberry time, which makes it even harder. You can hold them a while unopened in the fridge and then the florists can stretch it a little longer.” Lisa can choose from among 6,000 available varieties to extend the blooming season and to offer endless possibilities of color and form to wholesale suppliers of local florists.

Reclaiming the Soil

“That field over there that looks like a Christmas tree plantation [in miniature] is peonies,” Lisa points out. Ribbons of salad-makings in every shade of green and red stretch over the crest of another field. On a more distant hillside, a large white triangle is Reemay, covering a planting of peppers and corn. “The first corn didn’t come up so I bought the shortest season variety possible and I’m trying to replant it,” she explains. The Reemay adds heat and keeps the crows from pulling it up.” She uses special spikes to hold down the Reemay on her rolling, wind-blown acres.

Laughing Stock is a 19th century farmstead that hadn’t been farmed in many years. The fields had grown up to grass and brush, easier to reclaim than woods, but the pH was down to about 4.5. “I had this huge soil mat that nothing breaks down. The microbes couldn’t work right. When I open up a new piece I fallow it for at least part of the summer before I want to use it. It takes out a lot of weeds and witchgrass. You can’t pull it. You have to wear it out.”

She has added tons of lime and rock phosphate, greensand, and manure from a farm in Falmouth. “Now there are getting to be more organic dairy farms,” she notes, although certification rules allow the use of any kind of manure.

|

| Mesclun and other greens, recently cut, will rise again in December in this greenhouse. Lamb photo. |

Lisa uses a three-year rotation in her 3 acres under cultivation. In a fallow year she may have to cover crop and rototill more than once to get rid of the weeds. Buckwheat, which matures fast enough to till under in six weeks, works well for this. Depending on the time of year, she sows buckwheat again, or starts oats. “I’m still figuring out the right cover crops for here,” she says. “I like oats for overwinter if I can get them in early enough. Ryegrass gets huge in spring. Oats will winterkill. This year I’m using some crimson clover, Mammoth red clover, and a soil-building mix of oats, soybeans and vetch from Fedco.” The first year after that she plants close-seeded crops, such as salad mix, carrots, chard and lettuce. The second year, it’s all 3-foot spacing of peas, squash, broccoli, basil and the like, “that I can run up and down with a rototiller. Then it’s back to cover crop.” She adds that she is reevaluating her cover cropping system after hearing the Nordells’ talk at the Farmer to Farmer Conference last November. (See “Rotating Out of Weeds” in this issue of The MOF&G.)

Chickens and One Turkey

Lisa sells organic eggs from her flock of about 50 hens. “They don’t hold still, so I can’t count them,” she admits cheerfully. She’s not sure how many eggs she sells. “I’d have to look at a whole year. In March I have tons of eggs, but none to sell in winter. I’d have to push the chickens too much.” The chickens live in the barn with free access to an outdoor pen. A white turkey wanders around the yard, checking on all the activity. A couple of ducks join the poultry crowd, just for fun. “My six-year-old is disgusted with me because we don’t have a real farm if there are no animals. Birds don’t count,” Lisa says with her usual laugh. The turkey is a real buddy, however, according to Gail, one of Lisa’s helpers. Lisa notes that the crew have been known to wheel him across the brook in the tool cart, for company when they work in a far field. “Yesterday, when it poured, they ran out in the rain to bring him in and keep him dry. He’s young and not fierce yet.”

|

| Gail Taisey packages greens for restaurant and retail markets in December. Lamb photo. |

Making a Living

Lisa runs the farm by herself. Her husband is a project manager for an oil company in Alaska and isn’t home very much. Maggie, 12, Will, 10, and Katy, 6, help “when they want to earn money for something,” their mother says. “When they’ve earned enough, they stop. Everything is more fun than cleaning house. Hopefully they’ll catch on and at some time figure out they have to store up nuts for the winter.” Lisa does employ three helpers during the busy months. Last year one was a Bowdoin College graduate, waiting to return to school in the fall; one had just graduated from the Maine College of Art in Portland; and the third, Gail Taisey, comes from a farming family in Raymond. “She probably knows more than anybody else about it,” Lisa says. Gail stayed on to work through the winter. Lisa so far hasn’t had any apprentices. “I already have three kids,” she notes wryly. “There’s no place for apprentices to stay, anyway. I’m very happy to see them [her helpers] show up in the morning and very happy to see them leave in the afternoon. And I think they feel the same,” she allows with good humor.

“I don’t make my whole living this way yet, but I buy greenhouses and delivery vans and pay Gail God know how much. You should see the yacht she bought this summer!”

“That’s it right there,” Gail responds, pointing to the wheelbarrow.

Lisa grew up in New Jersey (the western, somewhat rural part) and hasn’t returned since she got a degree in soil science from the University of Maine. “I was glad when I hit the point when I’d been here half my life,” she grins. She also has a degree in civil engineering and is a licensed professional engineer and certified soil scientist in Maine. She worked for an engineering company designing hydrology and landfill projects. “I did that for about eight years, then quit to be home with my kids. When they got a little older, I started this.” She’s done with engineering, but the soil science knowledge makes it a lot easier to understand about soil amendments. “But it was only soil related,” she notes. “I didn’t have anything about diseases and insects, nothing about horticulture. It’s been very helpful in some ways and so is civil engineering – getting pipes in the right place, calculating the size of pumps needed, how to install extra-long ground posts for the greenhouses, figure the wind load. It’s very windy here and the soil is light, sandy loam. There’s no clay and no ledge to worry about for 70 feet.”

Though she doesn’t have a degree in horticulture or business administration, Lisa Turner has all the ingredients for becoming a successful farmer: more energy than a barn full of John Deeres, an extra helping of creative ingenuity, and most important, an unflappable sense of humor.

About the author: Jane Lamb was a regular feature writer for The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.