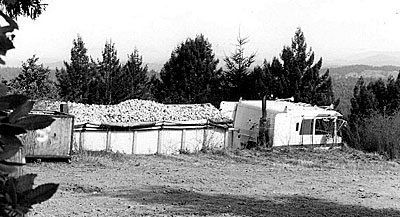

|

| Forty-year-old Golden Delicious trees thrive in this 26-acre orchard that sits 1200 feet above the Pacific Ocean, close enough for avid surfer Stuart Beck and his family to make a quick run to the beach. Lamb photo. |

By Jane Lamb

I met Stuart Beck’s apples before I met the grower himself. In the midst of the clamor and excitement of the annual family cider-pressing day, I couldn’t help noticing how sound and relatively unblemished were the apples going into the vintage machine. I was astonished to learn that the truckload of Gravensteins, gathered by simply shaking the trees over tarps and unceremoniously heaving them into the big pickup body, were all organic. Remembering the terrible catalog of pests and diseases that plagued organic apple growers I had interviewed for The MOF&G, I wondered if some California secrets might help Maine orchardists.

The steep, winding road up Greenwood Ridge from the spectacular Pacific coast in Elk brought me to the orchard where Beck was loading apples into one of two hoppers behind a big Peterbilt semi parked against the high-cut, roadside bank with just enough room for a log truck to pass. The driver, anticipating the 200-mile drive north over mountain roads to the Knudsen organic juice factory in Chico, paced impatiently. Beck worked steadily but calmly, dumping bin after thousand-pound bin of Golden Delicious apples by means of an ingenious tipping forklift rigged to the front of his ancient John Deere tractor. As counterweight, a second lift on the back held another bin of apples with which he topped off the load, 25 tons in all. The open hoppers were “tarped,” as they say out here, and the rig dispatched. Now Beck was free to talk.

|

| Surfer-orchardist Stuart Beck. Lamb photo. |

“When you called about this interview, I couldn’t imagine why,” he said. “I really don’t do much near the coast.” To a Maine farmer, struggling to grow organic apples, it would certainly look that way. Beck doesn’t irrigate, fertilize or spray, and hardly prunes. He’s at heart a surfer, who’s been raising organic apples for only five years.

“It wasn’t my intention to become an apple farmer. I’m an apple farmer by default – when I’m not surfing,” he says with his infectious grin. Sounds like California, doesn’t it?

Beck is a true Californian, a descendant of nineteenth-century settlers. His great-grandfather, originally from the Shetland Islands, was a farmer and cattle rancher in the Monterey area, but by Beck’s time there were no more farmers in the family. His parents moved 200 miles north to the Mendocino Coast when he was 16, and he graduated from Mendocino High School. He has attended several colleges (at 38, he’s just about halfway through, he says), between sailing and surfing around the world and working at such diverse jobs as building houses, timber salvage and real estate investment. When he bought the orchard in 1998, he had just come home for Thanksgiving from six months in Malaysia.

“I was planning to go back for another year. Then this real estate agent who has known me all my life said, ‘You’ve got to come with me to Elk to see this property.’ I remembered driving by and thinking, ‘If I could ever afford that, I’d like to live there.’ I’d been trying to move to Elk for 10 years.” (Elk, known as Greenwood before another California town with the same name won out, is 15 miles south of Mendocino, one of a string of small coastal villages that long served the farming, fishing and logging community.) Though he told the agent he couldn’t afford it, she insisted, saying the owner was desperate to sell and the price had come down. “She dropped me off at the top of the driveway, and by the time I’d walked down to the house, I was sold,” he continues.

|

| A half-ton box of organic Golden Delicious apples is loaded for transport to the juice factory. Beck uses an ancient John Deere “Frankentractor” and balances his load with another box on the back. Lamb photo. |

“This is the most beautiful property. You can see the ocean from the house. You’re up here in the sun, out of the fog, five minutes from the beach.” When he inspected the post and beam house, put together with dowels, he couldn’t believe it. He had built one house and had planned to build the next one with this method. Now it was already done – a “hippie” house, built in 1974.

“I bought the place with the idea of splitting off [and selling] the orchard, but I fell in love with growing and working with apples.” Beck had raised many organic gardens for his own use, but never grew anything on a commercial scale. He had 10 apple trees at his other house and innocently thought the only difference between 10 and 2,500 trees had to be just management. “In a way, it is,” he says, “but a lot more work.”

He gradually got the hang of it with help from other apple growers and plenty of trial and error. “I came into it totally [green]. I didn’t even know how to hook an implement on a tractor. I destroyed my tractor learning. I call my tractor the Frankentractor. It has parts from all different tractors. It works, it’s still alive. It has a unique personality.”

|

| This full truckload of Golden Delicious apples will soon become organic juice. Lamb photo. |

Eden on the Pacific

Also unique is Greenwood Gold Ranch itself, even for California. Beck likes to call it Red, Gold and Green Ranch after the Rome Reds, Golden Delicious and Rhode Island Greenings he raises. Most farms in California are called ranches, whether or not they have herds of cattle. Oddly enough, Beck has a corporation called Greenwood Farms LLC and markets his own brand of Greenwood Gold organic apple juice, a separate operation from the bulk sales to Knudsen. But he calls his 4-acre home orchard, fittingly, Eden West.

How else describe Beck’s idyllic situation? Thanks to a singular combination of geography and climate, he doesn’t have to irrigate, spray, fertilize or cultivate and hardly has to prune. The 26-acre orchard, half a mile down the road, is the “New Orchard,” added to the original holding long before he bought the property.

On the spine of Greenwood Ridge, which rises 1200 feet above the sea and overlooks the deep ravine of Greenwood Creek, the orchard enjoys more sunshine than the coast not quite 2 miles away. The combination of altitude and proximity to the Pacific and its frequent (but low-lying) fog creates an especially favorable environment for apples. The ground, well soaked during the November to May rains, isn’t parched by the months of drought that prevail in California, even on the coast. Beck is able to practice “dry farming,” difficult though not unknown, farther inland. “It tends to increase the sugars [in the apples]. Makes them sweeter. I have no irrigation system,” he points out with a touch of satisfaction. The coastal climate is blessedly moderate. Temperatures seldom drop to freezing in winter or go above 70 in summer, but behind the coastal foothills, frost is frequent in January and the thermometer regularly climbs above 100 degrees in August. “People from the East say you can’t grow a good apple unless it snows. Luckily, we do get snow, every couple of years,” Beck laughs. You won’t find a Cortland or a decent-tasting Mac on the West Coast, though, in this Mainer’s opinion.

No Spray, No Fertilizer

Beck doesn’t spray because he sells mainly to the organic juice market, which requires that apples be certified organic, but not necessarily beautiful. “I pick the cream of the crop and sell boxes to [local] markets. It takes quite a bit of sorting to get the good apples,” he admits. He has fewer pests and diseases to contend with. Mendocino County touches the edge of the apple maggot infestation that plagues colder northern counties and the rest of the Northwest, according to David Bengsten of the county department of agriculture. Codling moth, a major problem just a few miles east, is not happy on the coast, he added. Beck’s 2,500 trees, planted in the 1960s, include 800 Gravensteins, 800 Golden Delicious, 400 Red Delicious, and a fair number of Red Romes, all varieties that are especially suited to the coastal climate, Bengsten said. Beck also has Rhode Island Greenings, Jonathans and Kings, “one Cox’s Orange Pippin and one pear tree,” reserved for family and friends,” he notes, amused at these loners. He also harvests a couple of hundred more trees in a neighbor’s orchard.

Deer are a perennial problem here as in Maine. The only way to have a market or home garden is to put up a 6-foot fence. Beck doesn’t fence his orchards. “I have a lot of deer, but the trees are pretty mature. They nibble away at the bottom branches, but [most] are out of reach,” he says. Tell that to a Maine whitetail! The coastal race of black-tail (mule) deer are small, not a lot taller than a large sheep. He has rented his pasture to a sheep farmer but coyotes killed about 30 lambs and the farmer moved his flock to a neighbor’s fenced orchard where they could be more closely watched.

“I do prune when I have a good year,” Beck explains. “This year I’m going to prune. I have trees that haven’t been pruned in 15 years and they look all right. If that happened down in Boonville [in the Anderson Valley, 20 miles inland], the trees would be dead. They have to irrigate. It’s so hot and dry, so they have to prune.” Irrigation and pruning produce larger fruit, he says, but his aim is flavor, not tonnage. “The problem is that there’s not much money in [this business]. If I took all my profit from the last two years and put it into pruning, I’d have to prune again two years later. I do the bare minimum and the trees are doing fine. I’m going to prune this year, but in a different style, very light, just chain saws. You can go through pretty quickly and not spend an hour or two on a tree [hand pruning].” The cost of pruning is in hired labor, an absolute necessity for an orchard of any size.

Beck uses no fertilizer, though he says the sheep were great when he had them. “They ate the grass, fertilized. A big part of farming is keeping it cleaned up, which I haven’t done.” He has begun disking, however, at the urging of a friend who grows walnuts. “He was really adamant. I disked this orchard last year, and for some reason I have an incredible crop. My bumper crop [in this 4-acre orchard] was 20 tons the year before. This year I’m at 35 tons and still picking, so I think I’m going to get 45 to 50 tons. I don’t know if it’s because I disked or the weather, or what,” he speculates. “The idea is that you disk and the grass turns upside down, locks the moisture into the soil, which is real important for dry farming. You’ve got to do it at the right time of the year, just after the last rain. Everything in farming is right timing. And you can’t predict.”

While the athletic Beck doesn’t mind work, there’s one chore he truly relishes. “The best thing about the apple farm is mowing in the springtime. It’s incredibly meditative. The whole orchard is in bloom, you’re going through a forest of apple blossom, the smells mingling with the mowed green grass – it’s magic.” He doesn’t mind that it takes him “forever,” because he’s interrupted often by a thousand other demands.

Hanging on to a Tradition

When Beck purchased the 30 acres of orchard, they had been farmed organically since 1975, though he isn’t sure if certification existed then. The orchard was established in 1960 by descendants of the original settlers who had cleared the redwood forest for pasture. It had changed hands only once before he bought it. The Red Romes were planted for a now-defunct baby food company. Of his annual production, averaging 200 tons, about 120 tons, mostly Golden Delicious, go to Knudsen’s, a nationally-known label owned by Smuckers. Beck’s own Greenwood Gold Organic Apple Juice comes in two favors, pure Gravenstein and Golden Delicious, which is blended with Rhode Island Greening. The juice is processed in a custom cannery in Sebastopol (45 miles south) that presses, bottles and stores it. A distributor places it in grocery stores, restaurants and delis. Beck markets three to five thousand cases of 12 one-quart and 24 10-ounce bottles a year.

Even without the cost of fertilizer, irrigation, pesticides and heavy pruning, apple growing is only marginally profitable. But “I really do like it,” Beck insists. “If I could make fifty or sixty thousand dollars a year, I’d really like it,” he adds, smiling. “Selling to Knudsen’s, I make a little bit of money. Making my own juice I make a little bit of money. I have rentals [of small houses] on the ranch. That makes a little. Everything has a little piece here and there.”

Beck, like a small number of surviving apple growers, has found a niche for his product, but even these tenacious folks, Bengsten explained, are barely hanging on. The once-thriving apple industry in Northern California has been decimated by a complexity of factors, he said, among them the development of warm-climate varieties such as Fuji, Gayla and Granny Smith, grown a great quantity in Southern California; the development of controlled-atmosphere cold storage; and the global economy. It was serious enough when imports from Chile and Australia hit the market, but with the addition of China to the mix, it’s disastrous, he said. Hundreds of thousands of acres of apples have been pulled up in all of the Northwest. Grapes have taken their place in many cases, but now even that industry is being threatened. Beck thinks this has helped the market for organic apples and antique varieties. “All of a sudden the price of apples has gone up,” he says. “It’s finally becoming a [worthwhile] business. Up to this year we’d been getting the same price for apples as in the 1950s. We still need to get twice as much as we’re getting to make some ok money.”

Beck is now one of only four commercial apple farmers in Mendocino County who are in big production. The biggest of these is the conventionally operated Gowan Ranch in Philo, which has been in the Gowan family since 1876. With 110 acres under production, the Gowans market thousands of tons of apples, their own apple sauce, juice and preserves, as well as a wide variety of fresh fruits and vegetables at their roadside stand and farmers’ markets. Diversity is the key to survival, they have found. They’re reviving once-abandoned antique apple varieties to meet a growing demand. Their cadre of employees includes 20 thinners, eight pruners, and up to 80 in packing and shipping during the harvest season. Workers’ compensation, insurance and overhead are their biggest costs.

The Apple Farm, also in Philo in the fertile Anderson Valley, is an entirely organic operation, but Tim and Karen Bates must irrigate, thin, prune and spray with sulfur as many as 13 times a year to fight their greatest foes, scab and codling moth. They maintain 2000 trees, from seedling to 100-year-old specimens – 60 varieties of apples and a dozen varieties of pears, on 16 acres of river bottom. They specialize in antique apples, including some old varieties known in the Northeast – Northern Spy, Rhode Island Greening, Spitzenberg, Fall Pippin and others. Focusing on rare varieties as well as diversifying with their organic vegetables and homemade jams, jellies and pickles keeps them in business. They keep two or three people on the regular payroll and up to 10 during harvest. Pomo Tierra, a small organic orchard in Yorkville, west of the Anderson Valley, maintains 600 old trees.

Stuart Beck keeps his operation going with the help of his indispensable, 74-year-old, Mexican head man, Guadalupe García, called “Don” Guadalupe out of respect. Guadalupe came to California from Mexico in 1960 and did the first pruning of the original orchard. He has worked on the place ever since, now with the help of his son, Guadalupe (Lupe), and four or five other members of his extended family, joined by their wives, aunts, uncles and cousins and numbering as many as 15 during the harvest season. The obligatory farm dog, a black Lab called Lupito, came with the orchard in 1998.

Beck pays his workers well, and Guadalupe has been able to build a home in Mexico, where the family goes for a winter vacation. “I don’t know what I’ll do when Guadalupe doesn’t want to work any more,” Beck says. “He brings me lunch every day, homemade Mexican food. His wife makes it and sells it at a local shop.” Beck, his wife, Dulce, originally from Brazil, and their infant son, Tiago, divide their time between the orchard and their town home in nearby Mendocino.

Organic and Environmental

Growing up in California, where organic is pretty mainstream, and Mendocino County, the epitome of organic, Beck has been eating organically most of his life and growing his own gardens for 20 years. “I’m really strong on organics,” he says. “I rarely eat food that’s not. When I bought the farm, it just seemed appropriate.” Since it had been organically farmed since 1975, he didn’t have to wait three years for certification, the same rule that applies in Maine. “I’m happy that I was already certified before a lot of changes in certification since the USDA [regulations kicked in]. They might have made it more restrictive, with a lot more paper work. Besides, why use pesticides that cost a lot of money? To grow a good apple for market, it has to have no imperfections. That’s why I make juice.” Beck is certified by the California Certified Organic Farmers organization, of which he’s a member.

He has considered adding grapes to his operation. As far as culture is concerned, there’s no difference between a grape and an apple, he says. “Most grapes are grown organically, but a lot of grape people won’t call their wine organic because the wine industry has such a bad rap on organic wines.” Grapes are often dry-farmed in California, as they are in Mediterranean climates, but need irrigation to get started. Among other considerations, he would have to have a bigger well for that. “I’m an organic farmer, but I’m also an environmentalist. There’s no difference between a grape and an apple. It’s still a monoculture.” Beck would like to diversify, realizing that for family farms, which he considers his to be, it’s the way to go. “I’d like to do crops between the rows of trees, garlic, vegetables, lettuce, but I don’t have the water. You have to irrigate. I’d like to have a vegetable truck farm and sell at farmers markets, get full retail, cut out the middleman. I know farmers doing two, three, four, five thousand [dollars] a week.

“One good thing about growing organically, I do get more money for the fruit. But I’m also dedicated to doing stuff for the environment. I think organic is better for the environment. You’re not supporting chemical industries, putting all those pesticides into the air,” Beck asserts. He runs biodiesel in his tractor. “I think it costs me another third as much, but it has 95 percent less pollutants. It’s important for my own health. I run my car and trucks on it, too. It costs me extra money but it’s worth it in the end. I haven’t made my own [biodiesel] yet, but I’d like to. It’s where part of my money goes. I guess it’s idealistic, but I’d rather have a simpler lifestyle and do something better for the environment, and for the world.”

No doubt Stuart Beck shares a philosophy with Maine organic apple farmers, but it’s not likely they can practice many of the methods that work so well for him in the very different climate of California’s North Coast.

About the author: Jane was The MOF&G’s first and longest-term feature writer. She has “retired” to northern California.