|

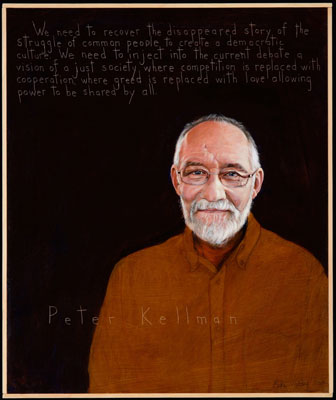

| Peter Kellman’s portrait by Robert Shetterly. From AmericansWhoTellTheTruth.org. |

In August, Maine artist Robert Shetterly unveiled his portrait of longtime labor leader, historian and working class hero Peter Kellman at the Good Life Center in Harborside, Maine. The portrait is part of Shetterly’s Americans Who Tell the Truth series. (MOFGA’s Russell Libby was also included in this series.)

Kellman, a lifelong activist who has spent most of his life in Maine, has been heavily involved in trade unions and participated in the civil rights, anti-war, anti-nuclear and environmental movements.

He and his wife, Rebekah Yonan, are now trying to grow all their nutritional and caloric needs using primarily human labor – using some of the skills he learned when he worked for Helen and Scott Nearing in 1964.

Kellman’s quote on Shetterly’s painting reads, “We need to recover the disappeared story of the struggle of common people to create a democratic culture. We need to inject into the current debate a vision of a just society where competition is replaced with cooperation, where greed is replaced with love, allowing power to be shared by all.”

At the unveiling, Kellman said that providing information about the technology of organic agriculture is good – but we also need to create a different culture based on cooperation and love, not on competition and greed. He is fostering this different culture as he mentors a MOFGA journeyperson.

Q. You worked for the Nearings when you were about 18 years old. What did you do for them? How did they influence you?

I was there for the fall months of 1964. I worked on building the stone wall around the garden, did some harvesting, cut firewood, built compost piles, helped dig the pond and asked many questions on economics and gardening. It was probably the most peaceful two months of my life.

Q. How are you and your wife doing with your attempt to grow all your own food?

Last year we were at a million calories toward the 1.4 million we need. I think this year will be about the same, but ask me again after the harvest is finished. Growing our nutritional needs isn’t a problem; but for the calories, having reliable grain crops – flint corn, wheat, oats and dry beans – is a new learning curve, especially the harvest side along with working them into our diet.

Q. Which MOFGA journeyperson are you mentoring? What do you discuss when you get together?

Max Boudreau of Winslow Farm in Falmouth and his co-workers.

When Rebekah started the North Berwick Farmers’ Market, we met a lot of young farmers. We organized monthly winter potlucks with those young farmers. That’s how I got to know Max, who asked me to be his mentor.

I said I was interested in talking about everything except how you actually grow food. There’s a whole history to the culture of agriculture. What kind of cultural supports do we need for small farms to succeed? How do you build organization around agri-culture?

Getting local farmers together socially in their area is one level of organization. Next is the neighborhood – just to go out in teams and meet people within a mile or so. Tell them what you’re doing. Ask them to come by. If that’s successful, then organize a barbecue or potluck or something to bring the neighborhood together so that they understand what you’re doing and the role they might play.

Another area of organization involves the people who live on the farm. Have a way to talk about what they want to do with the farm.

These are things Max and a couple of coworkers and I talked about at our first meeting. I sent them a copy of a movie called “The Accountant” (available on Netflix), about a small farm in the South. The movie gets into corporations and the culture of agriculture. I also asked them to look at “The Unsettling of America.” Wendell Berry did a panel discussion in 1974, which is on the Internet; in about 15 minutes you get the basis of “Unsettling.” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1tioiBrZRE or search “Wendell Berry, Agriculture for a Small Planet Symposium, July 1, 1974” on YouTube.)

I’ve had a lot of experience in organizing. That’s what I can bring to the mentorship.

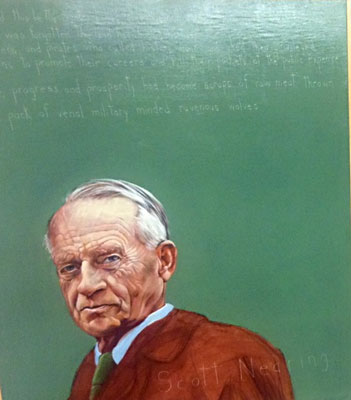

|

| Robert Shetterly’s portrait of Scott Nearing, one of Kellman’s early mentors. Photo by Sarah Bigney. |

Q. MOFGA’s farmers, gardeners and consumers have a long history of cooperation and sharing – through the Common Ground Country Fair, the apprenticeship and journeyperson programs, the Farmer to Farmer Conference, The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener and more. What else would you like to see MOFGA do in terms of fostering cooperation and love?

I was a member of the York County MOFGA chapter back in the 1970s. I think it is time to talk about why many active chapters stopped functioning, what we learned from that experience and what we have learned since.

MOFGA has evolved from a grassroots, locally driven organization (in my experience) into a staff-driven state organization, and a very good one. I’m not being critical of what MOFGA has become; I think what MOFGA does is great.

That being said, I think if we are to build a society rooted in agri-culture based on cooperation and love, we need to consciously work on building layers of dependency on each other in ways that make sense.

For starters, MOFGA could promote a dialog on the subject of how we begin to change our institutions toward what I’m calling a New Agri-Culture – like what I’m doing with Max.

In Jeffersonian democracy, most people would have a small farm. There were times when people and movements wanted a society based on equality, and agriculture was key to that. A dialog could explore that history plus experiences we’ve had – what happened in the ‘70s, with MOFGA and with the back-to-the-land people. That movement came out of the war, the ‘50s, a lot of things. Very few people who were doing back-to-the-land farming in the ‘70s are still doing that.

Also, MOFGA transitioned from having a lot of active chapters in the ‘70s to being a state-level organization. There were conscious decisions – a way to keep things going. They’re worth examining. If you know where you came from, you know where you can go.

What do we need for people to actually make a living at farming? Many CSAs and people making a living at farming didn’t buy the land themselves, but it’s family land or it was gotten through a land trust.

In 1900, 50 percent of the population was engaged in agriculture, with an infrastructure to support that. For one of my first jobs in high school, I worked in a slaughterhouse near Sanford. In the ‘60s we had a lot of small slaughterhouses. People were working in factories but were still farming. Maybe they raised 300 chickens. They would take them to the slaughterhouse, and they were distributed to the small stores. Now the slaughterhouses and small stores are gone. Those kinds of institutions allowed people to make a living or part of a living in agriculture. What would it take if, once again, we wanted a lot of people to make a living growing food?

Most people I see making a living with organic vegetables are not selling to people who shop at Walmart. It’s not the mill workers shopping at the farmers’ markets. How do we change that?

The book “Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760-1820,” by Alan Taylor, tells the history of central Maine – of Revolutionary War soldiers who moved there just wanting to have a cow, harvest firewood, do subsistence farming. But General Knox, who, with Washington, wanted to bring about a commercial empire, obtained a charter to the land and said the settlers had to buy or rent their land from him and had to grow wheat, which was easy to transport, instead of corn and potatoes. So war broke out – which is how the towns of Liberty, Unity and Freedom got their names. They weren’t looking for money but for security, to grow their own food. Knox won.

So we can look at those issues – who controls farming? Wendell Berry’s “The Unsettling of America” juxtaposes agribusiness and agriculture. We need to think about what that means; how we went from culture to business, and how we reestablish agriculture and democracy.

Agriculture is something people can do. Even if you have a tiny garden, you have an attachment to growing food. Not everybody has to be a farmer. The Victory Garden movement of WW I and WW II was clear about the importance of gardens: If you grow just enough beans for five meals, that’s five meals that can go to the troops. Once people start to grow things, their life changes. It’s their soul; it’s part of a cultural shift.

We can look at language, too. Before the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution, the language relating to farmers was very positive; then powers that wanted to shift the economy to industry began to use words like “shit kickers” as a deliberate move to get people off the farm and into the factories; to convince people that the greatest thing was industry, not farming and democracy.

How do we change things now so that farming is the future?

Q. The fight against competition and greed seems endless, but we keep at it – through saving seeds, for example (for its own sake and to counter the attempt by multinationals to control crop seeds). Do you have any advice for readers about steps they can take to fight competition and greed without burning out?

I think burnout comes from thinking if we can just win this battle, then we can go home and everything will be all right. So we drop most everything and concentrate on that battle or campaign. When it is over we are exhausted. If you approach change and politics as part of your everyday life, like eating breakfast, reading or weeding, then you build them into your life in a sustainable way.

It is something like what happens when you try to farm an acre when you only have time for a kitchen garden. The kitchen garden will bring you joy and some food. The acre will burn you out.

If we look at change as a process rather than an end in itself, if we see ourselves as travelers on a road that people before us started to build and our job is to continue the process, move us farther down the road and just leave something for the next generation to build on, then we can be at peace, because we will have done what we can.

MOFGA Chapters

For contact information for existing MOFGA chapters, please see the masthead on page 44 of this issue of The MOF&G. For more information about MOFGA chapters, including their activities and the process for starting a new chapter, please see https://www.mofga.org/Contact/Chapters/tabid/234/Default.aspx.

A September 30, 2014, conversation on WERU between Robert Shetterly and Peter Kellman appears at https://archives.weru.org/specials/2014/09/weru-special-93014-shetterlykellman/.

And an essay by Shetterly about Kellman, “Feeding the Roots, Building Democracy: On Painting Peter Kellman,” appears at www.commondreams.org/views/2014/09/30/feeding-roots-building-democracy-painting-peter-kellman