By Will Bonsall

MOFGA is celebrating its 50th year at a tumultuous time in our nation’s history. I am mindful that the organic movement was born out of tumultuous times. The year 1971 found us in a soul-wrenching war in Vietnam, a growth-thwarting oil crisis and a number of challenges to democratic institutions. So, what has changed? Nothing and yet everything as we continue to face new threats to all we hold dear. And, as in 1971, MOFGA continues to be the standard-bearer for some of our highest aspirations. Perhaps it behooves us to take a look back.

In 1971, I was just out of college, newly arrived on my undeveloped acres in Industry, Maine, struggling with my draft board and trying to eke out a living with few relevant skills. It was the height of a new wave of migration from other Northeastern states, based on Maine’s affordable land and relatively unspoiled environment – much like today, by the way. I was rather aloof from others doing similar things – no time, no car – but I heard about a newly-formed group of organic-minded folks and decided to check it out (I had been unaware of a precursor group, the Maine Organic Foods Association). They were for the most part a more radical bunch than I, but I myself was being rapidly radicalized by the times. Believe me, organic was radical – you didn’t find Rodale publications at the checkout counter then.

In those days, MOFGA’s whole entity was tucked into a little office in Hallowell, struggling for relevance. Few Maine farmers either knew or cared about its existence. Then someone got the (foolish, I thought) idea of having an organic fair. “With what?” I wondered. No land, little money and no experience with such things. But without fools going ahead with cockamamie schemes, nothing worthwhile would happen in this world. In fact, that first fair was so successful by every measure that MOFGA went from being stone broke to having enough revenue to make a number of educational grants, of which I was one of the beneficiaries, plus a surge of new memberships.

I attended that first Common Ground Country Fair in Litchfield with my partner and an elderly neighbor. I was blown away by the good energy (if a bit funky and chaotic) of the event and was determined to participate the next year, again at Litchfield fairgrounds. The feedback was, to say the least, encouraging – hey, lots of people cared about this stuff, and not just us counterculture types. We expanded our involvement as the Fair moved to Windsor and ultimately to its own digs in Unity. I knew the neighborhood well, having spent many summer days on a nearby dairy farm (now the site of Unity college), but this new place was about a very different vision of farming.

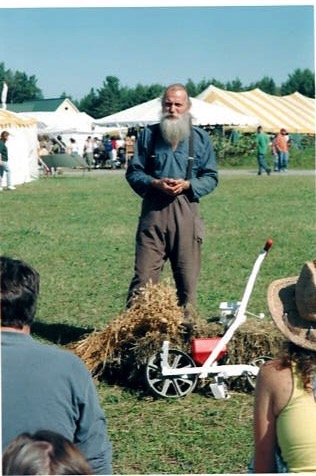

Will Bonsall leading a demonstration at the Common Ground Country Fair. Jean English photo

In the beginning, my association with MOFGA was quite peripheral, other than the Fair. I was not growing for market, and so the whole organic certification thing was off my radar. But the gradual proliferation of activities – Seed Swap & Scion Exchange, Spring Growth, Farmer to Farmer, Grow Your Own Organic Garden, Daytripping, the Low-Impact Forestry, Apprenticeship and Journeyperson Programs, the no-spray register, even this newspaper – drew me in even as I was striving to do my own thing.

Since I’ve recently become involved in a nonprofit business enterprise intended to enhance local self-reliance for food and energy, the commercial face of organic has become more important to me and my fellow board members (yes, some of us get to be in our seventies before deciding what we want to be when we grow up). Not only is organic certification crucial for our public image, we’re also finding the MOFGA price advisory listing invaluable – how much are snow peas selling for this month?

MOFGA’s Common Ground Education Center. English photo

MOFGA’s advocacy for organic is not limited to certification. Its legislative committee has had an outsized influence on the state’s political scene. They have spoken with a loud and clear voice – and been listened to – on questions involving spray regulations, GMOs in the marketplace, and food and environmental safety issues in general. Even at the federal level, MOFGA has been a reckonable player when the USDA tried to shape national organic standards to suit the mainstream (including GMOs and hydroponics).

MOFGA continues to foster seemingly quixotic projects that are ultimately vindicated by success. Perhaps MOFGA’s crowning folly-turned-success is the idea of planting a heritage apple collection on the steep bank of a sand pit. But go look at that project today (please, you’ll be glad you did!) – that orchard has limitless potential for education about genetic heritage preservation, not to mention restoration of devastated landscapes.

John Bunker offering apple identification at the Common Ground Country Fair. English photo

To fully appreciate MOFGA’s impact, one has to look at other states and their organic organizations. When Kent Whealy, late co-founder of Seed Savers Exchange (SSE), was keynote speaker at the 1985 Common Ground Country Fair, we walked around the fairgrounds and he exclaimed, “My, we could never do anything like this in Iowa!” In Iowa? Heart of farm country? Yes, but by its very nature not so friendly to progressive agriculture. And what about California, source of so much of the nation’s organic food? Largely corporate, an industrial sort of vision of what is organic. Just the fact that so much of MOFGA’s membership base (over 7,000) are not market-oriented (MOFGA certifies about 500 farms) sets it apart as a more alternative group and less than a mere trade association. I travel a great deal (as a presenter at other states’ organic conferences) and, believe me, as wonderful as they all are, MOFGA is the gold standard to which others aspire, especially our Common Ground Country Fair. These are more populous states, generally wealthier states than Maine – so how does MOFGA get to be MOFGA? Maine’s seeming drawbacks – size and poverty – may be its greatest assets. Maine farmers want to make a living but not by sacrificing a certain quality of life. Also, in a smaller pond you can be a bigger frog, and MOFGA members can have an outsized influence both in Maine politics and culture.

MOFGA’s history is an outgrowth of Maine’s history. A unique set of circumstances, including more affordable land, old Yankee values of self-reliance and an appreciation of Maine’s rugged beauty by out-of-staters, all have led to a wave of homesteaders, including the liberal academic set from the Boston area and beyond, who view Maine as a refuge.

By the way, MOFGA’s history is so full of devoted and effective individuals, you may notice that I have mentioned none of them. It’s because I would miss someone whose contribution was pivotal in MOFGA becoming what it is today and I’m terrified of doing that. But moreover, it’s also that MOFGA’s successes have been a collective effort, the general seeking for common ground. It is by forging ahead with that cooperative mentality that we will continue to generate our greatest good.

About the author: Will Bonsall lives in Industry, Maine, where he directs Scatterseed Project, a seed-saving enterprise. He is the author of “Will Bonsall’s Essential Guide to Radical Self-Reliant Gardening” (Chelsea Green, 2015). And indeed, he is also a distant cousin of another exemplary Maine horticulturist: Tom Vigue. You can contact Will at [email protected].