|

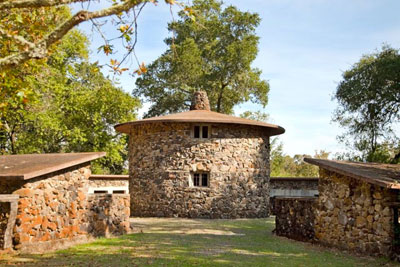

| Jack London’s Pig Palace. Photo courtesy of Jack London State Historic Park, https://jacklondonpark.com/. |

By John Koster

Superstitious windjammer sailors once believed that mentioning the word “pigs” was bad luck, but for some Duroc Jerseys at Glen Ellen, California, one old-time windjammer sailor was very good luck indeed.

Jack London’s “Pig Palace” was one of the final high points of his farming career. London had made his early literary reputation writing books about dogs and wolves that thought and felt as if they were human – and of a human named Wolf Larsen who thought he was an animal. Buck, the canine hero of The Call of the Wild, perhaps kindled a lifelong belief in kindness to animals that, combined with London’s fabled, almost compulsive abilities as an organizer, led him to build a house any pig would have taken pride in. The Pig Palace was constructed in 1915 during London’s last full year of life.

“Among other things I am starting to build a piggery that will be the delight of all the pig-men in the United States,” London wrote. “It will be large and cheap in relation to the size of it.” The rounded structure in the center was a feed room, and each sow and her piglets had their own “apartment” with a sun porch in the front, and an outside run in the back for healthy exercise.

The spectacular Pig Palace was also efficient: One man could care for 200 pigs, one valve could fill all the water troughs in each suite, and the pigs themselves, contrary to the usual practice when London was growing up, were kept sanitary as well as well-fed.

“The piggery was, indeed… advanced and successful,” wrote Andrew Sinclair, one of London’s more critical biographers, “…with a central feed tower acting as the hub of the surrounding circle of pigsties.” Visitors had to step into antiseptic footbaths to keep germs from contaminating London’s prize hogs on their sterile concrete floors. His vision was a true forecast of future farm methods – including, unfortunately, the odd notion that cows should be kept in towers and centrally fed, leaving their elevated stalls only for a monthly holiday on the grass.

Significantly, some of London’s animal-husbandry concepts didn’t work well – but his insistence on the use of cow manure and green manure to revitalize worn-out soil was one of the first adaptations on Franklin Hiram King’s writings about agriculture in China, Japan and Korea to reach American fields. At one point London even paraphrased Farmers of Forty Centuries in describing the best agricultural methods for the tired soil of America. Family and Farming Background London grew up on a series of farms. His mother, middle-class runaway Flora Wellman, had conceived Jack out of wedlock with an astrologer named William Chaney, who dumped her. Wellman was unable to nurse London, so Virginia Prentiss, a former slave, became London’s surrogate mother. Wellman later met and married Civil War veteran John London, a kindly alcoholic. John worked hard but to no good effect – Jack moved 18 times during his first 13 years of life and, unable to make many friends, became a voracious reader, a Socialist, and a would-be writer.

Jack London’s 1904 visit to Japan, Korea and Manchuria as a war correspondent marked the first time he rode a horse, and introduced him to the practical use of organic farming as described by King in Farmers of Forty Centuries, published the year before Jack rediscovered agriculture.

What sent Jack back to the farm was his excursion on the Snark, a schooner he designed and ordered built after the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. The shortage of construction materials while San Francisco was being rebuilt, and jobbery and foot-dragging by union labor, not to mention some sloppy work, drove the cost of the boat up to $30,000 – several times over the original estimate.

London’s docile Korean valet, a highly intelligent young man, took one look at the Snark and quit rather than sail. Others he booked, except for future wildlife photographer Martin Johnson, squabbled among themselves and jumped ship.

Jack – who described himself as a Socialist and a white supremacist to his literate blue-collar readers – survived the cruise of the Snark with the help of his wife Charmian, Martin Johnson, two Japanese teenagers he picked up in Hawaii, and two Tahitians who picked him up in the South Seas. When Jack ran the Snark aground in the Solomon Islands, he sold it for $5,000 and headed back to the States by steamship with Charmian and Yoshimatsu Nakata, the most reliable of the Japanese youngsters. Nakata became a virtual adopted son. The cruise shook London’s trust in organized labor unions and his systematic racism.

London had trained himself to produce 1,000 words a day, every day, and found that with two hours of work daily he could provide for his core family, his first wife and two daughters, his mother’s family, Prentiss, and his boyhood friend Frank Atherton. To occupy the rest of his time, as an adventure in scientific agriculture and a flight from alcoholism, he decided to succeed where his step-father had failed – by progressive farming.

Building a Model Farm

London had originally bought the Hill Ranch in Glen Ellen, California, in 1905 to escape from San Francisco. He had just published The Sea-Wolf, arguably his greatest book – and had ample income from royalties and short stories.

“There are 130 acres in the place,” he wrote, “and they are 130 acres of the most beautiful, primitive land to be found in California. There are great redwoods, some of them thousands of years old.” He subscribed to agricultural newspapers and took some university courses. London had actually loved his drunken stepfather, John, and remembered talking with him, before John’s death, about how to build a model farm with purebred livestock and the right crops for the climate. In 1910-1911, he started.

He acquired a full-time manager, his stepsister Eliza London Shepard, whose hasty marriage to her much older husband had collapsed. She was one of the few people besides Charmian and Nakata who turned out to be trustworthy.

London learned that the Kohler and LaMotte ranches, near his own domicile, had worn out and were regarded as useless because the owners had tilled the land for 40 years without fertilizer or fallowing, depleting the soil as American frontier farmers had for generations.

“My neighbors were typified by the man who said: ‘You can’t teach me anything about farming; I’ve worked three farms out,’” wrote London.

But London had seen farms in Korea and read about farms in China that had been worked for 40 centuries and could still feed families on just a few acres and even produce some cash crops. He also realized that the failed farmers had bred whatever livestock they had around the barnyard, instead of finding the best breeds for the climate. With his income from writing, London could afford to do better.

The task was big: “At the present moment I am the owner of six bankrupt ranches,” London wrote when he was starting out. He felt such an affinity for the land that he constantly poured money from his writing back into the farms, which gave him a certain leverage lacking among other farmers who tried to live off handicrafts – “Do you realize that I devote two hours a day to writing and ten to farming?” London earned a million dollars from his writing in the days before federal income tax, and he plowed it into the land.

“The ranch is to me what actresses, racehorses, or collecting postage stamps, are to some other men,” London wrote. “From a utilitarian standpoint I hope to do two things with the ranch: (1) to leave the land better for my having been; (2) and to enable thirty or forty families to live happily on ground that was so impoverished that an average of three farmers went bankrupt on each of the five ranches I have run together, making a total of fifteen failures to make a living out of that particular soil.”

London conferred with Luther Burbank, a personal friend, who recommended spineless cactus as stock feed – and provided the perfect potatoes, and plums to be raised and turned into prunes, a popular fruit before refrigeration.

London and Burbank also decided that Jack needed Jersey milk cattle, Angora goats, Duroc pigs and Shire horses. London loved the big Shires, with their massive strength, a quality he admired in men, women and beasts. He wanted only the best, and his insistence led to some indignation.

“Where under the sun can I buy a thoroughbred Jersey cow?” he wrote in a letter to the Pacific Rural Press. “I have answered advertisements in your columns, and all the offerings I get in reply to my letters are Bulls, Bulls, Bulls. I haven’t learned the art of milking a bull. What I want is a thoroughbred Jersey cow. Can you give me any clue for the obtaining of same?”

Tree Crop Backfires

London looked for a short-term cash crop while he was fallowing some of the land and detoured into eucalyptus trees. California had once been so teeming with oaks that a huge and peaceful Indian population sustained itself in scattered tribes once the Indians learned to leach the tannin out of the otherwise indigestible acorns. When first Spanish, then Mexican, and finally Anglo-Saxon settlers arrived, they virtually exterminated the peaceful Indians and eradicated the sprawling oak forests for lumber, firewood and grazing land for cattle.

The oaks didn’t grow back in the dry climate, and by the first Arbor Day in 1872, California had the lowest level of forestation of any state – less than 4 per cent. Some settlers from Australia introduced eucalyptus trees to produce lumber and firewood. Shortly, the eucalyptus tree was extolled as a natural wonder in its own right: The trees would cleanse the air; drinking eucalyptus tea would cleanse the kidneys; and smoking eucalyptus leaves would cleanse the lungs. Eucalyptus shingles were said to be fire resistant. The roots would soak up ditch water and swamp water now being associated, for the first time, with malaria and yellow fever.

In 1910, London ordered 30,000 eucalyptus seedlings from a nursery. The baby trees cost only $100 per 10,000, and after paying laborers $1.75 a day to plant the seedlings, London had all the makings of a forest of wonder trees for less than $500. He added more trees, and by 1915 he had 65,000 to 80,000 eucalyptus trees on the once-bare hills. He also signed an endorsement of commercial eucalyptus farming that touched off a eucalyptus boom in California.

The investment backfired. Australian eucalyptus trees, growing slowly, sometimes produced plausible hardwood, but California eucalyptus grew so fast that when the wood was lumbered it often warped and buckled and was all but useless on construction work. Eucalyptus railroad ties were so hard that they bent spikes. Worse, the oily branches and leaves proved highly flammable, rather than fire resistant. London died in 1916 before the full repercussion of frantic eucalyptus promotion became common knowledge.

He took another bath by planting grapes for wine without knowing that shipping the grapes would cost more than selling them would bring in. A commercial advertisement for Jack London Grape Juice took up some of the slack, but Jack became a supporter of Prohibition in any case.

Organic Approach Enriches Farm

Gradually, fallowing and manuring and London’s insistence on quality livestock worked. He had two 40-foot cement-block silos, the first in California, built between 1912 and 1915 to hold silage made by chopping green fodder plants. He hired Italian stonemasons to build a stone manure receptacle and an elaborate system to gather and store liquid fertilizer from his cow barn in 1914. The hero of his last and strangest novel, The Star Rover, is Darrell Standing, an agronomist who boasts that he can calculate butterfat by one look at the milk cow.

“No picayune methods for me,” London wrote shortly before his death, when his writing and his farming, in tandem, had paid off almost all the mortgages on his residential properties and thriving ranches, even as the drinking he tried so hard to overcome and his raw-meat and raw-fish diet were destroying his kidneys. “When I go in silence, I want to know that I left behind me a plot of land which, after the pitiful failures of others, I have made productive… In the solution of the great economic problems of the present age, I see a return to the soil. I got into farming because my philosophy and research taught me to recognize the fact that a return to the soil is the basis of economics… I see my farm in terms of the world, and the world in terms of my farm.”

About the author: John Koster is the author of Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in the White House Triggered Pearl Harbor and of Custer Survivor.