|

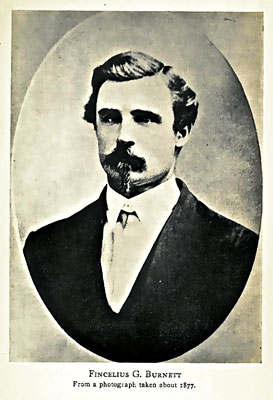

| Finn Burnett. |

By John Koster

The final round of treaties that the United States signed with the Indian tribes of the West in 1868 provided the tribes with government farmers to help them learn the white man’s agricultural techniques. The treaties also provided frontiersman and former Missouri farm boy Finn Burnett with a job that could feed his family while he helped teach the Indians to feed themselves. Burnett persevered through raiders, rattlesnakes and other distractions, but most of his troubles – like those of the Indians – came from government bureaucrats.

Burnett had been a freighter, a gold prospector and a section hand on railroads when he was offered the position of “boss farmer” on the Shoshoni Reservation at Wind River in 1871. He got the job through his old friend Dr. James Irwin, who had been appointed as Indian Agent for the Shoshoni tribe. The government gave Burnett $65 a month, plus a home, food, fuel and light – tallow candles and coal oil for lamps. He could also purchase clothing, blankets and equipment at cost from the government commissary store. With a new wife and baby son to care for, Burnett jumped at the chance – even though his previous experience with Indians had including gathering body parts after the Fetterman Fight and ducking arrows at the Hay Field Fight during Red Cloud’s War of 1866-68. The young husband had been a farmer in Missouri before the Civil War, but left to avoid being drafted into the Union Army and spent the next few years engaged in risky business. Being a government farmer was a safe job – or so it seemed.

The Wind River Reservation in Wyoming had been established in 1868, and the government planned to turn the Shoshoni, friendly to whites but with no agricultural traditions to speak of, into self-sufficient farmers and to educate them at schools on the reservation. By the time Burnett arrived in 1871, seven log houses awaited him, his wife, and other government employees at the reservation. Burnett’s new log house, with a living room with a big stone fireplace, pleased him and his wife. They were less pleased to find that Arapahos in the region were still tangentially on the warpath, at least as far as the Shoshoni and the Agency staff were concerned. The soldiers, however, had orders not to fire unless fired upon in the hope that things would simmer down.

Once the government employees had their houses furnished, they constructed a stronghold just west of the dwellings with 2-foot-thick sandstone walls pierced with loopholes on all sides, and with a foot of dirt thrown on the roof, in case of fire arrows. The single door was made of five layers of 2-inch planks, and a well dug in the center of the stronghold floor provided water in case of a siege. Provisions for a month lined the walls. Agency employees regularly slept in the bastion, with bedding on the floor, and four men took turns standing guard each night. They used their log cabins only in the daytime.

Moccasin tracks were sometimes found in the dust outside the cabins – the Indians were probably more curious than hostile. When Burnett later asked Arapaho Chief Black Coal why the Arapaho had never burned the empty cabins while the whites were huddled in the sandstone fort, Black Coal simply replied that the thought had never occurred to him.

The farming equipment hadn’t arrived in time for planting in 1871, so the government employees used their spare time to construct 24 log houses for those Shoshoni who consented to live in them.

In 1872, the government farmer’s job began. The Indians who turned out were divided into teams, Finn harnessed the horses to the newly arrived plows, and the agricultural history of the Shoshoni commenced. Some of the Indians had a tough time learning to plow, and some of the warriors insisted on riding the plow horses while the women steered the plows, but the work got done – sort of. At least a dozen teams broke loose and ran away dragging harness.

Finally, 320 acres were plowed and 268 were sown with wheat, 40 with barley, 10 with oats and 2 with potatoes. The Shoshoni then took off to hunt and the whites started digging irrigation ditches. The first ditch – said to be the first in Wyoming – sluiced water to the fields on June 15. The first harvest was a huge success: The wheat crop was bountiful, and the potatoes were “large, smooth and moist in their cool nests.”

Haying season, however, brought on the problem of rattlesnakes. The sounds of the haying machines were augmented by the rattles of dozens of snakes, and while the blades sliced them to pieces, even the dying rattlers could bite – and those whose rattles had been separated from their heads struck without warning. One day Burnett and his friend Uncle Billy Rogers were cutting hay with John Kingston, who was notably deaf after a bout of scurvy as a Union prisoner at Andersonville during the Civil War.

“Hey! There’s a rattlesnake in this load!” Kingston shouted.

“You couldn’t hear one of them rattle if it was right beside you,” Uncle Billy shouted.

“Well, I may not be able to hear a rattlesnake, but I can smell one,” Kingston said. “They have a scent like a green cucumber.”

Burnett and Rogers kept forking the hay until Uncle Billy climbed to the top of the heap on the wagon – and instantly jumped off.

“Say, there’s a rattlesnake up there,” Uncle Billy said. “It was almost against my nose when I saw it.”

Nobody laughed again when Kingston smelled green cucumbers in the hay fields.

Snakes could be avoided. Bureaucracy was something else. As early as 1874, the Indian Bureau ordered defective mowing machines and cultivators through sweetheart contracts. In another case, surplus equipment rusted because Burnett couldn’t obtain planks to build a barn for it.

As the wild game gave out, the Shoshoni became dedicated farmers. But the bureaucrats didn’t help, and Burnett noted the background of the first Indian Agent he worked with: “… the major had been the leader of a glee club which had campaigned through his home state during [Rutherford B.] Hayes’ presidential campaign, with a six-horse team and wagon… the officer’s trade had been that of a tailor, but that being drunk had been his principal occupation for the past few years…” This agent, after many drinks with various cattlemen, approved an order allowing Indians to sell their cattle, and within a few years the entire herd had disappeared.

Another was “a professor from Georgia, who brought to the agency a number of his relatives and friends who displaced many of the experienced employees on the reservation. These newcomers became noted only for their whiskers, as each of them had grown a tremendous beard …”

Yet another was “a captain of the United States Army who was understood to have received his appointment at the request of his superior officers, who wanted to be rid of him … it was commonly known … that he was a morphine addict.”

At this point, the government moved the Northern Arapaho tribe, who were blood enemies of the Shoshoni and outnumbered the Shoshoni two to one, onto the Wind River reservation, despite protests of the Shoshoni. The Arapaho Chief Medicine Man had, oddly enough, been the principal spokesman for the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho who had offered to take up farming voluntarily two decades before, but had been rejected because Congress didn’t want to spend the money and perhaps because some Congressmen believed that the Indians would shortly become extinct. But the quality of the agents improved and Burnett kept right on farming.

Hundreds of acres were plowed, and by the time of the Spanish-American War, the Shoshoni, now reluctant hosts to the larger Arapaho tribe on the Wind River Reservation, were raising all their own grain and selling the surplus to the Milford flour mill. The Indians sometimes even used their annuity checks to buy new seed. At one point, Burnett was fired because he distributed seed on the basis of how much the Indians planted – the most industrious farmers got the most seed. But Theodore Roosevelt read about the incident and Burnett got his job back.

The bureaucrats often made such a mess of distributing seed grain that Burnett and the employees convinced the Indians to save some of their own seed instead of waiting for Washington. Prosperity was restored, and the Shoshoni did so well as farmers that they paid Burnett a tribute for his efforts as the government farmer: They ceded part of the reservation to him and his family so that they could have a farm of their own. And there they lived happily ever after.

About the author: John Koster is the author of Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in the White House Triggered Pearl Harbor and Custer Survivor. Suzie Koster assisted with the research for this article.