|

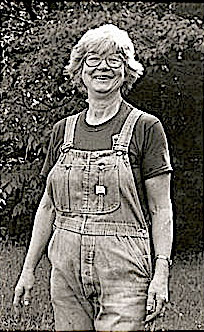

| Betty Weir. Photo courtesy of Mary Weir. |

by Julia Davis

One August morning a few months before her death, Betty Weir spoke to me emphatically about the importance of young people learning to grow food and about what she had accomplished independently over her lifetime. Remembering Betty after her death to cancer last year, those close to her stressed her opinionated and independent nature.

Betty was usually blunt and straightforward, according to her daughter Mary Weir. “You knew where you stood with her. She was not a submissive woman. She always wore the pants in the family.” These traits helped Betty achieve her dream of owning a farm and working it into her eighties.

By August 2007, when I talked with her, Betty had suffered numerous health problems and treatments, including a knee replacement, ovarian cancer and chemotherapy. She died that December at 84 years old, leaving behind friends and family who remembered a strong woman passionate about growing food.

I knew Betty through the Winter Cache Project, a community-based initiative to grow food to eat through the winter. Betty and her son Gene Weir opened their farm to the grassroots group from Portland to teach skills Betty thought were vital and to get help with their own crops. Betty talked to me from the chair where she often sat in the cluttered house where she lived with Gene. When she did get outside that summer, she usually rode a four-wheeler called the green machine, giving advice and directions and wearing a big straw hat. Dealing with her physical decline and giving up control over the farm she worked so hard to buy and improve was clearly difficult.

Betty detailed her first gardening experiences: Her great-grandmother, a slim florist who lived with her family during Betty’s childhood, directed her on planting and caring for flowers. Betty’s mother taught in Washington County and her father was president of the Royal River sardine factory in Yarmouth, a seasonal enterprise.

In 1940, Betty graduated from high school in Washington County and started business school in southern Maine. She worked first as a secretary and then in the post office, retiring in 1984 after 30 years there. She moved to a half-acre plot on Main Street in Cumberland in 1949, where she and her husband raised their three children. They had a vegetable garden and small goat herd there, Gene remembered. He and his sisters worked in the garden.

Betty had always wanted a farm. When she found an old one on Pleasant Valley Road in Cumberland in foreclosure in 1966, she went for it. The previous owners hadn’t farmed, so Betty, with help from her husband and children, improved the land and buildings over time and called it Pleasant Valley Acres Farm. She bought and paid for the farm herself, Betty said proudly and stubbornly, as someone accustomed to hard work and to the barriers to a woman living in a largely man’s world.

“I was a compulsive gardener,” Betty said, describing how she grew and gave away vegetables and raised goats and cows. She became an expert in humane and healthy ways to raise pink veal and helped regulate the practice. When animal right’s advocates started to decry veal practices, the market declined and Betty stopped raising veal calves.

In the 1980s, Betty met Marilyn Settlemire and Sue Sergeant, who shared a stand at the Brunswick Farmers’ Market. They had more space than they needed, and Betty had more vegetables than she needed, so Betty joined them in 1988 and stayed at the market for 19 years before moving to the Crystal Springs Market for four years and then organizing the Cumberland Farmers’ Market.

“We’d be at the farmers’ market and she would dicker with people, but she really liked to socialize,” Mary said. Sue said Betty would take care of customers with Women, Infants and Children (WIC) government vouchers, giving them a little extra. “She would say, ‘there’s nothing to be ashamed of if you’re poor.’”

A distant suburb of Portland, Cumberland changed while Betty lived there. “All the fields are growing houses,” said Cumberland Farmers’ Market vendor and apple farmer Connie Sweetser in April. Betty, concerned with the change, pushed for a market to support and promote local farmers. She became the founding president in 1987, when the market opened.

Betty was also involved in the early years of MOFGA and helped organize the animal area of early Common Ground Country Fairs.

Gene and Betty’s 10- to 15-member senior farm share, started around 2001, had 72 members by 2007, and Gene started a CSA in 2007 as well.

Betty followed her own ideas and inspiration, employing her own farming techniques and learning through reading and experimenting.

“Her father called it, ‘the lazy man’s way,’” Gene said, describing how his mother always tried to find an easier way to do any task. Her farming techniques were low-key, Gene said, and she never incurred much debt. She taped a dowel to a hoe to make uniform holes for planting garlic, and she spread goat manure directly on fields and rotated crops instead of composting, figuring that manure in the field would break down sooner or later. She designed a stirrup hoe, which her husband then made from a barrel stave. She mulched with cardboard, paper from baby goat pens, goat hair and other farm waste.

Sue described the frugal woman’s farming style as simple, remembering her recycling whatever she got her hands on, including used yogurt containers, milk cartons and newspapers.

Betty initially farmed organically because she couldn’t afford synthetic chemicals, but her dedication to organic grew, Mary said, especially after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring inspired her. Mary said her mother saw similarities between herself and Carson in their poor backgrounds and struggles pursuing male professions. Both “had to find things to do to inspire their minds.”

Betty enjoyed teaching others how to farm and thought young people, especially, should know how to grow their food. For the last several years, she let members of the Winter Cache Project use some of her land to grow food to store for winter, in exchange for helping Betty and Gene with their crops. She gave advice to inexperienced group members.

“My mother was sincerely concerned that we were not going to know how to grow our own food,” Mary said, adding that Betty advocated preserving farmland and farmers. A woman of vision, she wondered who would grow food in the future and was concerned that children didn’t know where food comes from.

Sue said Betty, a believer in hard work, struggled to haul vegetables to market and animals to the butcher despite knee problems, creating tools to make it easier for her.

“Life was so difficult for her but you didn’t know that,” said Marilyn Settlemire’s husband, Tom, who called Betty a pioneer. She did so much on her own in a male-dominated world, Sue added.

Losing mobility in her later years was especially hard for this active, independent woman. In September 2005, surgery and chemotherapy for ovarian cancer caused some nerve damage. Several months after a knee operation in April 2007, cancer returned. She died that December.

Gene carries on the farming, expanding what Betty started, and the Winter Cache Project still trades labor for land and advice. Betty’s legacy lives on.