By Lea Camille Smith

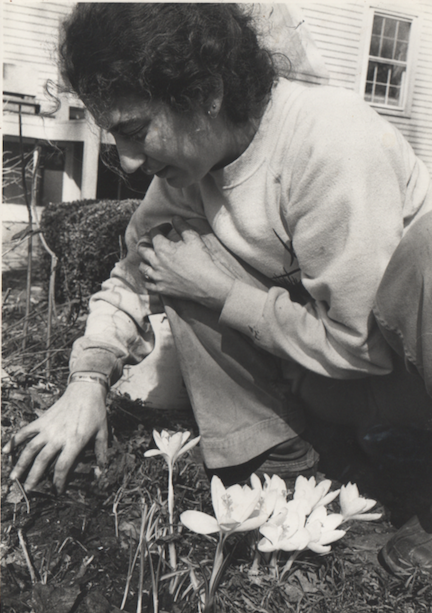

Hands: any gardener would have trouble arguing that they are not our greatest tool. Test the moisture of the soil; delicately separate the roots of a new planting; place a seed a quarter of an inch below the surface. The tiniest weeds require finger-tip precision. Gardening gloves can sometimes give us the dexterity of an elephant. So, we strip down to the bare skin and meticulously pick the tiny clover from between the rows of small furry carrot greens. I can tell a fellow gardener by their hands: a backyard manicure of soil-rimmed nails, all the lines in the skin filled in like a web of dirt roads. Gardeners’ hands wield the tools: trowels, hoes, buckets, clippers, rakes and so on. We wipe the sweat off our brows, tie our boot laces a little tighter, adjust our hats.

Imagine gardening with one hand behind your back.

At 28, I am the same age as my mother was when — in 1988, two weeks after marrying my father — she suffered a major spinal stroke. She collapsed in the shower after a popping noise in her cervical spine caused a cascade of tingling, burning, numbing pain. Then she was paralyzed.

My father slept on the hospital floor or sat vigil by her bed for a month until her toe started moving again, beating the small odds the doctor had predicted. In time, the rest of her body followed, including her hands, though forever changed. Still, she charged through two high-risk pregnancies to birth my brother and me, and she returned to her work as a gardener.

“A cashier asked about my hands when I finally went out again after the stroke,” said my mother a few years ago, facing her palms towards me. Big, sturdy working knuckles were contrasted by atrophied thumb muscles, like hollow pools, where her thumbs connect with her palms. The aftermath of severe nerve damage and death.

“What did they ask?” I wanted to know.

“What’s wrong with your hands?”

In 2011, the summer after my freshman year of high school, my mother came home from her long-time gardening client with dirt in her smile lines and a purple bandana barely hanging onto her head. She asked if I’d like to come to work with her the following morning at 8:30. I’d been lollygagging at the soccer field and down by the harbor, avoiding my dad’s inquiries about handing out resumes. I agreed. I grew up following my mom around our gardens in Searsmont and then Rockport, Maine. I might as well get paid to do it.

My mom worked for her boss for decades. She owned a house a few blocks from the ocean in Rockport, tucked behind tall hedges. Driving by, you’d never know that kiwi vines, dozens of roses, a few vegetable gardens and a small pond flourished there. I walked around the yard with my mouth open, trailing behind my mom on the moss-covered stone pathways. I looked from my mother, as she motioned to various plants along the pathways, to the gardens, and back again. From the artist to the art.

My mother and I worked together for three years. We complained about the summer heat, the fall chill; we found the best trees with the most coverage to pee behind; we laughed manically as we plopped hungry potato bugs into soapy water; we talked about our fears.

For three cycles of spring, summer and fall, we existed together, tucked away behind the hedges. I learned how to spread mulch, deadhead a dianthus, wrangle tomatoes. We picked duckweed from the pond, crossing our fingers that we didn’t miss any of the invasive and prolific sprouts. I began to understand the language that it takes to commune with the flora. One day, I hoped to speak this language fluently.

Then, we would go home, where she would ask me to help her open a salsa jar. “My thumbs just can’t do it,” she’d say.

A few years later, after moving down to Portland and pouring beer at a local brewery for a couple of summers while I was in college, I itched to get back to the plants. When I got a gardening job, the first person I called was my mom.

“I knew you’d find your way back,” she said.

On my first day with a small landscaping company out of North Yarmouth, I found it strange that we packed so many tools in the truck for spreading mulch: wheelbarrows, two types of shovels, garden rakes and landscape rakes. My mother and I used small buckets and our bare hands, crouching close to the ground with our hands in the mulch like we were searching for gold. Now, I was tasked with adding five new tools to this simple process. I’ll admit, we could cover a lot of ground with wheelbarrows and rakes, but it felt so impersonal to never primp and fuss with the mulch with our bare hands; my mother and I used to make it perfect that way.

That night I lay in bed, wondering why my mother and I had never done it like that before. I looked at my freshly scrubbed hands, still stained with dirt from my first day back, and I saw my own puffy, defined thumb muscles. There it was: adaptation.

How adaptive are we? In my lifetime, I don’t think I’ll get a quantitative answer to that question, but there are plenty of examples — celebrations even — of people put through grinding situations who come out the other side shining like a pearl.

My mother adapted the way she gardened so she could continue working in the spaces she loved. Therefore, I learned to garden without gloves and many heavy tools. I learned her gardening processes without knowing that they were adaptations.

At 28, my mother learned to eat, walk and talk again with less of her body than before. But when I see her in the gardens, it’s as if she is shielded from her past. She is complete. Nothing about the way she moves through a workday would invite questions about her abilities.

But it’s when she is outside the garden — when she encounters a peanut butter lid screwed too tight or a too-heavy box on a shelf, or a stranger decides to project their own insecurities upon her hands — that the past threatens to come roaring back.

We all need places to feel strong and safe; for my mother, it is with plants. If I call her on the weekends between April and November, chances are she’s answering her phone with dirty hands in her backyard, planting cucumber seedlings or pruning a bush with my dad.

Growing up, I never crawled; I scooted on my butt. One day I stood up and started walking. I got there in my own way; my mother tends gardens in hers.

Sometimes, I’ll pick up my water bottle with two hands to drink — exactly like my mother does, with one hand acting as the thumb. I can hold a bottle with one hand, but I don’t. The deepest part of my being still gravitates towards her way of moving through the world.

Lea Camille Smith is an MFA student at Stonecoast, an editor for the Stonecoast Review and a freelance writer. She resides in the Mount Washington Valley of New Hampshire. Her work can be found or is forthcoming in Island Ink, Mt Washington Valley Vibe and the Conway Daily Sun.

This article was originally published in the summer 2024 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. Browse the archives for free content on organic agriculture and sustainable living practices. Subscribe to the publication by becoming a member!