|

By Jean Noon

I operate a 50- to 60-ewe, organic sheep farm in southern Maine. During the fall of 2002 I learned through Coastal Enterprises about the Northeast SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) Grant Program. I was interested because I was worried that I would be unable to continue managing my flock organically under the newly implemented organic standards, which, as updated in 2002, require only natural materials to treat parasites in sheep and lambs. While we have always used organic farming practices, we had been allowed to worm our sheep with Ivermectin. We had reduced the proscribed worming schedule to twice a year and were not worming meat lambs unless they appeared to need it. A lamb that needed treatment would be held from slaughter at least 40 days. During 2002, the health, growth rate and feed conversion of my lambs diminished alarmingly and we did not use Ivermectin, as it was not permitted.

Being skeptical of organic wormers but unwilling to abandon my organic market (or the organic ideal), I used two commercial, organic, approved products – unsatisfactorily. Feeding rates and methods of using these materials have not been established adequately for lambs. The materials are supposed to be mixed in the feed, but as my lambs grow they have free choice access to organic grain, hay and pasture. Lambs did not eat the mixtures all at once, and I was concerned that some would eat too much or too little. I was not convinced that the treatments were effective, so I took fecal samples to my veterinarian and was told that my lambs needed treatment for parasites. I treated the poorest lambs with Ivermectin; they recovered and were marketed as nonorganic.

Searching the Internet for controlled experiments that supported the effectiveness of organic materials, I found none that were convincing. I did find references indicating that garlic, with 28 antibacterial compounds, might be effective.

For this SARE Grant I designed and implemented a controlled experiment to measure the effectiveness of two commercial, natural wormers and garlic barrier juice. At the same time I identified naturally resistant ewe lambs to retain as breeding stock. I have followed the work on genetic resistance to parasites of friend and Maine shepherd Dr. Tom Settlemire, who agreed to advise me and showed me how to take fecal samples and identify and count parasites.

About Our Farm

The Noon Family Sheep Farm is a MOFGA-certified, organic sheep farm. We have been raising sheep since 1970 and winter 50 to 60 ewes. Our original Columbias were purchased indirectly from the UVM flock dispersal. Since then the flock has evolved into a mix of Columbia-Rambouillet-Leicester-Suffolk-etc. bloodlines, including colored and white wooled brood ewes. We market value-added lamb directly at fairs and festivals through our lamb barbecue food booth. We also sell hay, wool, yarn, sheepskins and lamb at the farm, a part-time operation except during fairs and during lambing and haying seasons.

We own about 75 acres and lease 25 to 30 acres of hay land. We have about 8.5 acres of pasture, and about 15 acres of our own hay land onto which we rotate sheep after haying. Our fencing is mostly electric, permanent and portable. The sheep harvest most of the second and third crop of hay directly. The balance of our farm is managed forest and wetland.

|

| Handling pens and chute facing south … |

|

| and facing north. |

|

|

|

|

| Lambs graze a 2-foot strip of new grass up to a portable electric fence. |

|

Project Activities

Fifty-one lambs (the 2003 lamb crop) were assigned to four groups by counting down the birth order (1,2,3,4; 1,2,3,4; etc.) without regard to birth type or sex. Groups were raised in one flock separately from adult ewes after weaning in late April. During 2002 I had introduced the lambs to pasture with the ewes before weaning to try to get lambs eating grass sooner. I changed my strategy in 2003, introducing lambs to pasture after weaning to keep the ewe parasite carriers from contaminating the new pasture. Lamb pasture had not been grazed by ewes since mid-November. I rotated the lamb pastures about a week after treatment. I had only four paddocks to use; more would be better. I started the lambs in a small area of grass and strip grazed, or moved the fence once or twice every day so that they grazed clean grass and ate it completely. They prefer grass that has not been walked on and contaminated.

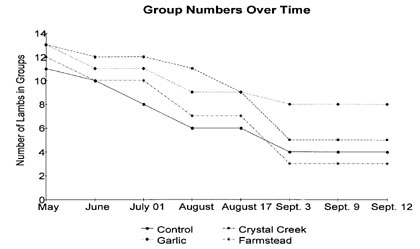

In the sorting chute, group membership was determined by ear tag number, and lambs were weighed, sampled and treated. Sampling and weighing started in May and were repeated every two to three weeks throughout the summer. Appropriate natural treatments were administered orally during every other testing session starting in June. Market lambs were live graded and slaughtered as they finished, starting in late June. The lambs grew fast and I was surprised and pleased as they reached market size. However this did remove them from their test group.

During August I separated the ewe replacement lambs into their own group to conserve grain and keep them from becoming overweight. They continued in the test.

Methods

Fecal samples were taken by placing the lamb in a crate (on the scale) in the sorting chute. Using a glove, a sample was removed from the lamb’s rectum. Two ml of fecal material was added to 28 ml FECASOL (sodium nitrate egg floatation solution). If no sample was available, the lamb was released and tried again later. Ear tag and sample numbers were recorded, and the lamb was treated appropriately.

Parasite loading was determined by the “Modified McMaster Egg Counting Technique” developed by Advanced Equine Products. Green line slides incorporate a fixed cover slide and a pair of grids that determine the volume of the sample and provide a way to count eggs within that volume. Eggs per gram are then calculated using a formula. The two grid numbers are added and multiplied by 50 to determine the eggs per gram in the sample. (See source list.)

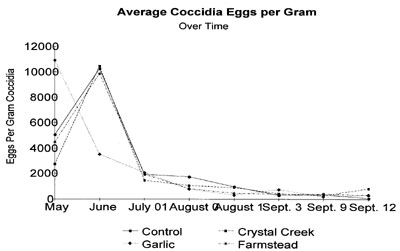

Coccidia (Eimeria), one parasite that I counted, live in the cells of sheep’s intestines. Sheep usually develop resistance to them over time, but they can be problematic in lambs. The graph shows that garlic reduced Coccidia before the natural drop in late June due to the rise in resistance immunity after exposure. (See graph to the right.)

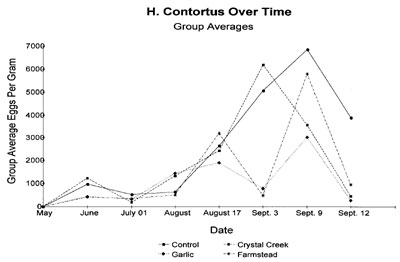

I also counted Haemonchus contortus (H. contortus), the barber pole worm, a bloodsucking intestinal parasite that is dangerous to lambs and has developed immunity to several commercial anthelmintics. (See graph below.)

Lamb Flock Management

All lambs had free choice access to grain, pasture, hay, loose trace mineralized salt mixed 2:1 with Diatomaceous Earth, ground limestone and water. Some experts are skeptical of the effectiveness of DE. Ground limestone prevents urinary calculi in ram lambs on a high grain diet.

Group One – Control – Lambs were not treated unless they had clinical symptoms and treatment was needed for survival; then they were eliminated from the experiment.

Group Two – Crystal Creek organic wormer – Para-Tack Intestinal Cleanser, 2 tsp. mixed with water to make a 1-oz. dose

Group Three – Garlic Juice, 1 tsp. concentrated juice diluted with water to make a 1-oz. dose. (This dose proved effective, but I would like to study the optimum dose further.)

Group Four – Farmstead Health Supply, 1/2 tsp. Sustain and 1 tsp. Restore mixed with water to make a 2-oz. dose. This mixture was too thick to administer as a 1-oz. dose

To be fair to the two companies, I did not follow their somewhat vague recommendations; this may have compromised their products’ effectiveness. Both catalogs seem to address mostly larger ruminants. I wanted to use a liquid dose because it is more time efficient and accurate.

My standard dosing syringe with backpack clogged with the dry mixtures from Crystal Creek and Farmstead, so I used a single dose syringe with a 6″ extension and washed and rinsed it thoroughly between lambs. This syringe needs to be handled carefully to prevent losing the dose on the way to administration. Crystal Creek and Farmstead both recommend mixing their products with the feed, but I could not depend upon lambs receiving equal portions that way unless I had individual stalls (or a LOT of time), so I mixed these products with water. I also wanted to run all the lambs together. Treatments were measured and mixed fresh in batches at each treatment date. Because the compounds do not suspend well, the batch was mixed each time a dose was drawn. I could administer the garlic solution with the standard backpack multiple dose syringe. (I used the single dose syringe until my last treatment on Sept. 8.)

Lambs were rotationally grazed together and moved to clean pasture a few days after individual treatment. I did not set aside quite enough “clean” space for the entire grazing season, possibly resulting in the dramatic rise of parasite load during August. I would like to study the timing of the parasite rise further, as it is crucial to the management schedule. The parasite rise may also depend on the weather.

Fecal egg counts were taken again two to three weeks after treatment. Weight gains and animal health were documented at each treatment and testing interval.

My data suggest that garlic juice reduces the number of eggs of H. contortus and Coccidia in fecal samples. The results were unexpected: I was skeptical about the effectiveness of any of the treatments. My first surprise came when the lambs did not show any infection with H. contortus at the May baseline testing session; only Coccidia were evident.

During June both parasites increased in numbers. H. contortus was mostly well below 2000 eggs per gram (not considered dangerous), but Coccidia were about 11,000 eggs per gram. The garlic treatment group dropped to fewer than 4,000 eggs per gram Coccidia.

By July the Coccidia had dropped in all groups including the control, indicating a rise in the natural resistance or immunity in all lambs. I continued to count Coccidia, but they stayed below 2,000 for the rest of the test.

The 2003 lambs grew very well, and the first ones were marketed in early June, so test group numbers declined. Most male lambs were marketed by the end of July, and by Sept. 9, all were gone. This made the weight record averages for the test groups inaccurate, as heavy lambs were pulled from the group and may have influenced the results. Also we had a lot of rain over the summer; because lambs were wet during a couple of sampling sessions, I did not weigh them. In August I started to put ewe lambs into a separate group, because I did not want to waste grain and get them too fat. Their weights leveled off and some declined.

By Sept. 3, I was concerned about the health of the remaining ewe lambs because of the rise in parasite numbers. Four developed evidence of bottle jaw. As they were from different groups, I surmised that they had low natural resistance to H. contortus. I gave these lambs garlic juice on Sept. 3 and treated all ewe lambs with garlic on Sept. 9, then tested all of them on Sept. 12, when all lambs showed a decline in egg loads. (All ram lambs had been sold by this time.)

One important result of this experiment is my heightened awareness and understanding of parasite life cycles and the importance of very careful pasture management in successfully raising organic lambs. August and September are critical months, and lambs may need to be monitored weekly for H. contortus.

Simplified Life Cycle of H. contortus (Strongylid Nemotode)

With favorable external conditions, eggs are shed in the ewes’ feces in the morula stage of development by parasites that are in the fifth or adult stage and are attached to the sheep’s abomasum. Individual sheep have widely varied infections due to inherited and acquired resistance to parasites and other factors, including age, exposure, nutrition, stress, arrested development (hypobiosis) and PPR (peri-parturant relaxation of hypobiosis at lambing). I don’t know whether PPR occurs when ewes lamb in February and March when barn temperatures are below freezing. These eggs apparently are the ones that must survive to infect the lambs. My data suggest that lambs were not infected from the winter bedding pack but developed infections after being on pasture for over three weeks. The greatest rise in infection did not occur until almost 12 weeks on pasture – apparently from larvae that hatched from eggs that overwintered on the pasture.

First stage larvae develop from eggs and hatch in a day or two to feed on microorganisms in feces. After a molt, second stage larvae also feed on microorganisms, but they must have contact with soil and warm, wet conditions. This stage averages about 20 days. Some eggs appear to survive in hypobiosis on pasture for over a year, so one winter is not enough to clean a pasture completely.

Winter lambing on a bedding pack does not provide favorable conditions for larval development, perhaps because of the lack of contact with soil. Eggs probably are not produced if parasites are in hypobiosis (another detail for study). This also would explain why my lambs did not exhibit H. contortus infection in May.

The second stage molt is started but not completed in the external environment, so the infective third stage larva remains encased in the cuticle of the second stage until it is ingested by a sheep. At this stage the larvae are most vulnerable to environmental extremes and most dangerous to grazing lambs. These larvae climb up grasses in warm, wet (dewy or rainy) conditions. They die from exposure to dry and hot or cold conditions.

Once ingested the sheath is cast off in the abomasums of the sheep; the now-parasitic third stage larvae attach to the sheep’s abomasums and suck blood. Next they molt to the fourth stage, which has not been reproduced in the laboratory yet.

The fourth stage sooner or later molts to the fifth or adult reproductive stage, depending on whether it enters hypobiosis. Ewes carry fourth-stage parasites in their abomasums that survive in hypobiosis through the winter to shed eggs again in the spring on pasture. If lambs are not grazed with ewes or on the same ground, they will not be exposed to such high rates of infective larvae.

During hypobiosis sheep remain infected but parasites are inactive and not reproducing. Hypobiotic parasites apparently can withstand anthelmetics. What triggers hypobiosis or how long parasites (or eggs) can survive in this state is unknown.

One H. contortus female may pass as many as 10,000 eggs per day under favorable conditions, so one sheep can pass as many as 30,000,000 eggs per day.

Weather and the parasite’s life cycle influence its management. If first stage larvae need an average of 20 days to molt into their second stage, then rotating pasture every two weeks and not revisiting a pasture for at least 30 days is wise.

Through this project, I worked with Dr. Tom Settlemire’s intern, Elizabeth McCain. She worked with Settlemire on the Katahdin Sheep Project and was certified and enthused by the FAMACHA© System, a visual comparison of the redness of the interior of the eyelid with a color chart to determine the degree of infection due to H. contortus. (The blood sucking parasite causes anemia.) I attended a training session on the FAMACHA© system and am excited by how much simpler it is than taking fecal samples to determine infections.

Economics

Testing individual fecal samples (penning, weighing, preparing lab equipment, collecting samples and recording sample and ear tag numbers) on 12 lambs took me (working alone) about an hour and a half. Preparing and examining 12 slides, calculating and entering results took about another hour and a half. This is about 15 minutes per lamb per sampling session. Starting with 51 lambs was daunting.

My veterinarian clinic charges $12/sample for lab work and did not identify or count parasites. Monitoring parasite loads economically and conveniently is an important best management practice. The FAMACHA© System is much more efficient and cost effective, and can monitor genetic resistance to H. contortus. Breeding for parasite resistance should reduce the need for treatments.

Garlic juice is less expensive than Ivermectin or the other treatments I tried. One gallon of Garlic Barrier cost $85 plus $9.19 shipping. (See sources.) I have been using 1 tsp. per sheep. I will continue to control parasites in my flock with garlic juice. I dosed all my sheep when I brought them into the barn for the winter and will treat them at lambing to reduce the possibility of PPR. I will also treat the adult ewes before they go out on grass. I am currently trying (with another SARE grant) to get a better idea of the optimum dose of concentrated garlic juice.

My Management Calendar

September 1: Ewes are turned into a third crop hay field (very clean of parasites) for flushing.

September 15: Rams are introduced to the flock.

November 1: Rams are removed from the flock.

November 15: (or when the ground freezes and ewes begin to need hay and water) – Ewes are brought in off pasture and are fed hay.

December 20: Ewes start to get supplemental organic grain, gradually increasing from 1/10 pound to ? pound per head over a week. Thin ewes are sorted into a separate group and are given more grain.

January: Sheep are shorn. Six or seven lambing pens (4′ x 4′) are set up.

February 5: Lambs start to be born. Ewes lamb in the flock group and are moved into a lambing pen for two to three days, then are moved into a pen with up to five other ewes with lambs for a few days before joining the larger group of lambed ewes. Lambs are given free choice grain in a creep feeder.

April 1: All lambs have been born. Ewes with Feb. lambs are taken off grain and are fed only hay in early April.

April 25 to 30: Feb. and early March lambs are weaned. Ewes are removed and dried off.

May 10: Ewes are moved to pasture. Weaned lambs are moved into dry lot with free choice grain, hay and access to winter cleaned pasture. Lambs’ pasture access is moved every 10 days.

Sources

FAMACHA© System:

https://web.uri.edu/sheepngoat/famacha/

Garlic Research Labs Inc., 624 Ruberta Avenue, Glendale CA 91201; 1-800-424-7990 FAX 1-818-247-9828

Farmstead Health Supply, P.O. Box 985, Hillsborough NC 27278

Crystal Creek Services, Leiterman & Associates Inc., N9466 Lakeside Road, Trego WI 54888; 1-888-376-6777; Fax 715-466-5842

Modified McMaster Egg Counting Technique (green line slides)

Olympic Equine Products (Advanced Equine Products), 5004 228th Ave. S.E., Issaquah WA 98207; 425-391-1169

To count eggs on green line slides, I purchased a binocular microscope for $329.95 with my own funds; it has a moveable platform and works very well.