|

| Ocean Glimpse gardeners enjoy the onion and corn harvest. From left to right in front, Wendy Meacham, Susan Pierce, Rossi Meacham, Sean Meacham; on the deck, Roger and Regina Knight with corn. Photo by Judy Berk. |

By Jane Lamb

When one of the highlights of summer is a bunch of grownups sitting on a deck spitting watermelon seeds at each other, something good must be going on. “When they’re ripe, we’ve gotta eat ‘em. They won’t keep, so we have a big watermelon harvest party. It’s great fun,” says Dave Foley – fun and the essence of the community spirit at Ocean Glimpse Farm, where Dave and his wife, Judy Berk, share their big garden space with seven other households in a unique cooperative gardening project.

Unlike many “community” gardens, no individual plots exist. It’s one whole organic garden, Dave explains. The garden flourishes on a third of an acre, on old farmland high on the westward side of Route 1 in Northport. Everyone shares in the planning, the work and the harvest. The “ocean glimpse,” Dave notes with a grin, is the tiny triangle of deep blue sea nearly a mile away, visible through a notch in the trees. Red Shirley poppies flash among the vegetables in their wide raised beds. Calendulas and sunflowers mark the end of a row here and there. “We nourish our eyes, too,” says Dave.

Specialization of Labor

Every member of the group has his or her own specialty. “We have the world champion hoe wielder in Roger Knight,” says Dave. “He’s the best guy at hoeing a straight furrow of anyone I’ve ever met.” Roger and his wife, Regina, joined the group several years ago. “We were new at growing food for storage. It’s been a wonderful gardening experience,” Regina Knight says.

|

| Celebrating a bounty of veggies and ribbons, from left to right: Regina Knight with fennel, David Foley with artichoke, Sean Meacham with pumpkin, Roger Knight with sweet potato, Wendy Meacham with sunflower head, Ivy Lobato with Blue Hubbard squash and more than five blue, two red and three yellow ribbons; Judy Berk with cauliflower, and Rossi Meacham with Nantes and Chantenay carrots. Photo by Sarah Holland. |

Wendy Meacham lives next door with her husband, Sean, and son, Rossi, on another parcel of the old chicken farm. “Wendy is the best finehand-weeder in the world,” Dave says, “and the longest-term member. In nine years she’s become comprehensively skilled at everything.”

For Susan Pierce, MOFGA’s special events coordinator and a near neighbor, a whole day planting in the spring or an afternoon of concentrated weeding fits her job schedule better than a little gardening every few days. Ed and Ivy Powers also like the big, all-day work parties. Wendy Meacham and Lisa Hawkins, another member, prefer to put in small amounts of time on a regular basis.

Longtime gardeners Lea Gerardin and Emanuel Pariser don’t have the space to grow such large field crops as corn and dry beans. “We were having trouble with late blight on our potatoes,” Dave says, “so we’re growing potatoes on their land and we’re growing corn and beans for them. It’s a good sharing arrangement. Essentially, it’s seven households that are full-time active partners.” One more, Bruce Morehouse, who recently lost his garden patch, is raising just four tomato plants, but may become a full-scale garden sharer another year.

Dave’s specialty is keeping the soil fertile, composting, tilling and deciding on cover crops and rotations. “I’m not really in charge,” he insists. “ We discuss everything among ourselves, but I make suggestions, see to the long-term fertility of the soil. My wife, Judy, is interested in raising seedlings and planting. The flowers are mainly her doing.”

|

| David Foley and Judy Berk’s energy-efficient house is the backdrop for a diverse planting of vegetables. Seedlings are started on removable shelves in the south-facing windows in the spring. The wide roof was designed to hold a solar water heater and photovoltaic panels eventually. Photo by Judy Berk. |

There are other kinds of contributions besides planting, weeding and harvesting. “Ed Powers and Sean Meacham like to be the carpenters,” Dave continues. “They erect the pea fences, the posts for tomatoes, the arbor for grapes and kiwis. Ed and Sean are the scarecrow designers. They did some really crazy things, like gazing balls and tin cans and pie plates. If it weren’t for Ed we would never think of growing crazy things like luffa sponges.”

A major Ocean View festivity is the Seed Summit around Christmas time, one of several potlucks that bring the whole gang together during the year. “We take all the stuff that’s still around, root-cellared or in freezers, and make a feast,” Dave relates. “We get together here and talk about what we planted last year, how much, was it enough or too much, do we still want to grow this or that, is there anything new. We get organized to do the seed ordering, then pool the order through Fedco and a few other sources, and map out what the coming year looks like.”

Special requests are common. “Ed said, ‘Let’s grow some luffa sponges.’ Nobody else would care, but why not? We have the space.” Dave admits luffa sponges don’t seem quite like a Maine crop, but they’re going to see how it works. “Maybe it’s global warming or something else, but we’re having luck growing things that used to be a lot more marginal when I was a kid. (Dave grew up in Dixmont.) We’ve been growing a fantastic batch of artichokes.” Although artichokes still have to be raised as annuals in Maine, last year Ocean View artichokes took a blue ribbon at the Common Ground Fair, along with their squash and leeks and a few other things. Some red and yellow ribbons came home as well. “We divided up all the ribbons,” Dave notes.

|

| Looking out over the curved beds at Ocean Glimpse Farm, you can just glimpse the ocean in the distance. Dry beans and asparagus grow on the left, and a buckwheat cover crop is at the far edge of the garden. Photo by Judy Berk. |

The Non-Boss Builds the Soil

Although he maintains that he’s “not in charge” and he uses the pronoun “we” in describing all the activities, the garden’s success depends to a great extent on Dave’s soil-management program. Rotation, cover crops for nitrogen fixing and green manure and a modified raised-bed system based on Eliot Coleman’s ideas are the basis. “When I first read John Jeavons’ work (How to Grow More Vegetables (1974), I was quite impressed,” Dave says. “I tried his double digging but it was pretty laborintensive.” About seven years ago Dave discovered that using a hiller-furrower attachment on a rototiller could achieve the desired effect with a lot less sweat. In the spring, after the entire garden has been rotovated by a neighbor with a big tractor, Dave marks out the beds with string and goes down the row with the hiller-furrower, which throws soil up in both directions. Six feet away he makes another pass, which forms the opposite side of the growing bed and starts the next one. “Then we blend in compost, rock powders and rake it smooth, to make the planting beds every year. By running the rototiller between the beds a few times during the season, we break up any hardpan in the subsoil and keep the weeds down between rows. This way we believe the soil stays fluffier and less compacted. Ever since we latched on to this method, we like it a lot better than row cropping, although if we were on a larger scale, there would be an advantage in using rows because we could use [mechanical] seeding equipment and cultivators.”

Handseeding is one of the more labor-intensive jobs at Ocean Glimpse Farm, but it’s one where everyone pitches in for big work parties. Planting is done by soil temperature, rather than date or phases of the moon. The cooling effect of the nearby sea delays the spring planting, but the sea’s heat sink prolongs the fall growing season. First frost doesn’t usually occur until late September. The combination of local miniclimate and excellent soil has produced very good yields, Dave says. None of the produce is for sale, by the way. This is strictly a grow-for-your-own-table operation.

|

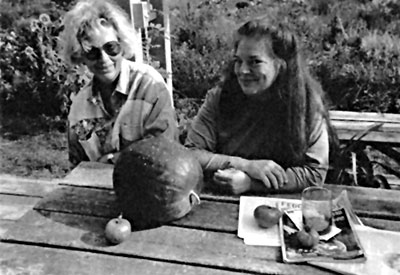

| Regina Knight and Susan Pierce with Green Zebra tomatoes, Moon and Stars watermelon, and catalogs from Johnny’s and Fedco. Photo by Roger Knight. |

Ocean Glimpse soil contained less than 1 percent organic matter when Dave and Judy began gardening there nine years ago. “Now we’re up to about 7.6 percent and we’re up in the high end of optimum range for all the nutrients, according to soil tests,” Dave notes with pride. “We make a lot of compost, purchase compost and manure, let it age. We use a lot of cover crops – buckwheat, vetch, clovers, winter rye.” Dave scavenges leaves from nearby towns in the fall and works them into the soil, along with colloidal phosphate, greensand, lime and wood ash from everyone’s wood stoves. “Every year I make up a barrel of ‘magic powder’ – alfalfa meal, a little colloidal phosphate, a little greensand, and sprinkle about a coffee can of that into each bed. That and organic matter seem to keep everything growing just fine.”

When a section is going to be left fallow for a season, Dave plants buckwheat for the summer to create a lot of biomass and choke out the weeds. To increase the nitrogen content, he’s been experimenting with a combination of hairy vetch, bell beans and clovers. Bell beans are a kind of dwarf fava bean, used strictly as a cover crop, that Fedco has been selling for several years. “I think they’re marvelous,” says Dave. “They produce a big, lush crop of nitrogen-fixing biomass quickly, and you can sow them in extremely cool weather in early spring. They’re becoming relatively inexpensive, so I think a lot of people are going to turn to them as a soil builder.”

Rather than the living mulch method, Dave prefers Eliot Coleman’s plan of sowing a succession crop of low-growing clovers, which germinate slowly under tomatoes, corn, squash and brassicas. By the time they’re up and growing, the vegetables are well established and able to compete. Everything gets plowed up the next spring. “It’s paid off handsomely, at least if soil testing labs are any indication,” he says. When the neighbor with the tractormounted rotovator arrives in the spring, Dave often finds himself running ahead of him with bags of leaves. “I usually use leaves as an addition to compost, but there have been times when I’ve thrown them into areas I’m going to leave fallow to till into the soil before I plant buckwheat.”

|

| An arbor supports hardy kiwis on the left and grapes on the right. The arbor was built with posts from the woods and scavenged boards when extra time and lack of money demanded a constructive project. Photo by Jane Lamb. |

Another Old Chicken Farm Reborn

Ocean Glimpse is part of an old Waldo County chicken farm that was subdivided. Dave and Judy have 12’A acres of woods and fields. The garden was once an apple orchard. The original house and barn are long gone. “There were caches of old, aged chicken manure when we first got here,” Dave relates. “We haven’t used it on the garden very much because of concern about spreading burdock seed. But we’ve planted close to a thousand trees and shrubs here, and use a lot of it as soil amendment when digging the planting holes. The old apple trees were here. Pretty much every other tree you see in the field we’ve planted over the past 10 years. Also, out in our patch of woods, I’ve been putting in hardwood seedlings, mostly oak and beech.”

They’ve planted sour cherries, pears, persimmons. “Well, we’re trying them as an experiment,” Dave responds cheerfully to a question about the northern range of that tender fruit, one more experiment with marginal crops as climate patterns seem to be changing. He’s also trying a few mulberries, an American-Chinese chestnut cross, butternuts, black walnuts and hazelnut-filbert crosses. Edibles for the birds include viburnums and elderberries, and grapes that do well when they can keep them from being edibles for the raccoons and foxes. Dave is considering breaking up the garden into more manageable sections, divided by hedges of highbush blueberries, raspberries, Siberian pea shrubs and such, as well as patches of such long-term crops as rhubarb, asparagus and strawberries. “Eventually we’re going to try to have garden beds in alleys between rows of edible shrubs,” Dave explains. Part of the rationale for raised beds between clearly defined paths is that nobody has any confusion about where to walk, even visiting kids and dogs, he adds.

Irrigation and Ornament

One of Dave’s pet projects is the pond he dug last year in a low-lying area behind the garden, partly for fun, but more for irrigation. The farm’s well can’t support the hotter summers that seem to be on the increase. “I’ve always known it was a suitable spot for a pond,” he says. “There’s a layer of clay not far down that holds the water. As soon as it was dug, a frog took over immediately and now it’s full of them.” He’s decided that an organic frog-leg ranch is not in the MOFGA spirit, however. More to the point is the importance of a water supply for the garden. “I found I could use a little two-volt bilge pump powered by a deep-cycle marine battery, which is charged by a very small photo-voltaic panel.” To his surprise, the sun has always kept the batteries charged. A hose leading to rain barrels slowly adds to the water collected from trie sky and goes to the garden in watering cans. “It’s a stopgap measure,” says Dave. “We really do rely on rain more than anything. This year we were close to desperate a few times, and the pond has saved the day.” The pond is nearly 5 feet deep at one end. The water level had dropped about 18 inches since spring, but in July Dave was waiting for it to go down a bit farther so that he could shovel out the sediment for use on the garden, one of Scott Nearing’s tricks. While the pond has ifs practical purpose, it’s also part of Dave and Judy’s landscape. They’ve planted basket willows, comfrey, daylilies, irises and ornamental grasses around its banks. A couple of more ponds, both practical arid ornamental, are in the future, Dave says.

Organic Growing and Growth

Dave grew up in Dixmont next door to Ben and Ariel Wilcox’s Peacemeal Farm and learned the ropes of vegetable farming from Ben as a teenager. His connection with MOFGA has been a long one. He remembers helping shovel a bulk shipment of rock phosphate from a freight car in one of MOFGA’s early cooperative ventures.

Later Dave studied agricultural and resource economics in grad school at the University of Maine, “a complete waste of time,” he says. “I’ve never used a bit of it.” More fruitful has been his degree in architecture from the University of California at Berkeley. He and Judy lived in California for four years before eagerly coming back to Maine. They started building their energy-efficient house nights and weekends 12 years ago, living in a camping trailer and commuting to work in Bangor.

Now Dave is in partnership with architect Sarah Holland, with an office in half of the Foley-Berk home. They specialize in environmentally-oriented architecture and often collaborate with other likeminded architects rather than competing with them. They designed the post-and-beam Common Ground education center and exhibition hall at the MOFGA fairgrounds in Unity, (see The MOF&G, Sept.-Nov. 1999) rather a long way from shoveling rock phosphate. “I have the best commute in the world,” says Dave. “I just go from the left side of the house to the right side, about 12 feet. Sarah has to drive 12 miles.” Judy is communications and public affairs director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine and has been involved in the removal of the Edwards Dam. Dave and Judy started their garden nine years ago.

Ed and Wendy Meacham were neighbors from the beginning. They were interested in vegetable gardening but didn’t have suitable soil. “We said, ‘Come on down and garden with us,’ and we did that for several years,” Dave relates. “Then some ^ others got wind of what we were doing and wanted to get in on it. So it’s just evolved.” When Roger and Regina Knight took advantage of early retirement in Massachusetts and wanted to build a solar house in Maine, they turned to Dave and Sarah. “In the course of designing the house and helping them build, we became very good friends and they asked if they could start gardening here,” Dave says. “So I think it’s all connected. A lot of what we do in our [architectural] work is oriented toward what we do in the garden. It’s just a different form.”

Green Beyond Gardening

For Dave and Judy, the web of connection goes beyond gardening and architecture. Taking a cue from Dave’s brother, Jonathan, a global climate monitor at the University of Wisconsin, they have made a practice of putting no net gain of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. “[Jonathan] has calculated how many trees he has to plant each year in order to offset the amount of carbon dioxide he and his family put out. It’s set up a little brotherly rivalry. We’ve worked our lifestyle down to a point where it takes about 55 trees a year for us to balance out the carbon dioxide we’ve produced over the past 10 years. We’ve managed to do about double that. I don’t count the ones that grow in the woods unless I’ve planted them myself.” Now that the 1,000 trees he’s planted have taken up just about all the space available, he’s wondering how to do better on energy conservation, perhaps by converting more to renewable energy sources.

“I’m hoping there will be green electricity supplies in. Maine after deregulation, and more funding for tree planting efforts. My brother taught me there’s a surprising amount of effectiveness in increasing organic matter in the soil/which sequesters carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In Wisconsin they’re not just doing tree planting but working on prairie restoration with Wes Jackson and the Land Institute [in nearby Kansas].”

Dave explains that organic matter in the soil “sequesters” carbon compounds rather than having them decay into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Having raised the organic matter on Ocean Glimpse’s third of an acre by 6.6 percent, he figures he’s made a step in that direction. Jonathan is going to help him figure out how many tons of carbon dioxide they’ve sequestered. “It’s actually quite significant,” he says. “Getting organic matter back into the soil is doing something good for the soil, our lives and the atmosphere.”

Dave sees the problem of carbon dioxide in the air due to deforestation and burning of fossil fuels as very scary, and one way he can help is by addressing the issue in his own back yard. “No one person is competent to heal a planet. We’ve got to learn to put our intelligence and energy to a scale at which we can be competent.” He and Judy burn about three quarters of a cord of wood in a 68% efficient Waterford stove to heat their very energyefficient house, use propane gas for cooking, water heating and a small amount of backup heat, and keep their electric bill under $30 a month for the house and office together.

“We built the house ourselves, very slowly, with cash on hand, and avoided the mortgage trap. We have a very low overhead, so I can afford to be selfemployed and work for outfits like MOFGA,” he says wryly. He points out that wood, though a fairly dirty fuel as far as particulates and some gases are concerned, does not contribute net carbon dioxide to the air when burned. “Carbon dioxide was stored in the tree. If the tree fell to the forest floor and was not buried, the C02 would be released into the atmosphere anyway.” But Dave believes solar energy and conservation should be the first fuel choice. “For supplement, coal is probably the worst, wood is ambiguous. If we had natural gas in the state, it would be an excellent choice.” He and Judy look forward to the day when they can have solar hot water and photovoltaics to feed electricity back into the grid. “I’d just as soon avoid the large bank of batteries it takes to get off the grid. I’d rather participate in .the grid as a cooperative thing, but be a small net producer of clean energy.” He’s hoping Maine people will have a choice of “green electricity” to buy from renewable sources, such as small scale hydro, wind and solar generation.

Community is Greatest Asset

“Cooperative” is the name of the game at Ocean Glimpse Farm. “We have a cooperative advantage in that people have different capital assets [as well as skills and time] they can contribute,” Dave continues. For example, the Knights raise seedlings for the garden in their built-in sunroom and are building a hoop house. “We keep the tiller and the mower here, but people chip in for gas money and repairs. It’s a very cooperative group, and in the past few years we’ve got a lot of experience [to share] under our belts.” Economy is another form of conservation they practice. “We’re thinking of mounting a chalk board under the porch roof to leave messages for one another. Here it’s a long distance call just two miles away. We’re trying to rely less on the telephone, more on e-mail.”

But above all else, Ocean Glimpse gardeners value their sense of community. “I’m very happy I lucked out and bought a house in the neighborhood,” says Susan Pierce, citing a long list of Ocean Glimpse benefits. “It’s great that there are people with a whole lot of growing knowledge. I didn’t have to learn everything from scratch. You get a chance to taste things you might not want to grow yourself, and maybe change your mind. It allows everyone more freedom. If you want to go away for a few days, you don’t have to worry about the garden. There’s great camaraderie. It’s what community is all about. You get more out of it than you put in. It’s a real celebratory experience. Gotta go. I told Judy I’d help her pull onions!”

A common interest in gardening aside, there’s the pleasure of getting to know people who may be quite different from yourself, Susan says. “The sociability is wonderful,” says Regina Knight. “It even makes weeding fun. I love choosing seeds, planting together. I love onions and garlic. I do a lot of cooking and I never had so much garlic. And the harvest, where everyone shows up and divides the produce, the potluck suppers…. “ But people come as often as not to work on their own and enjoy a private communion with the earth. Regina finds it a perfect place for her watercolor painting. “The arbor is such a good setting, and Judy’s flower garden is gorgeous.”

The number of households participating has reached the optimum level, Dave says. “You could easily get too many people. So far, in about 10 years of doing this, We’ve never had any sense that someone wasn’t pulling their weight. Year to year, it all balances out. One household this year is in the midst of building a new house and moving, so it was unrealistic to think they could do a lot here this year. They’re getting carried a little this year, but they’ll be back in the middle of things again.”

The whole Ocean Glimpse cooperative grew out of an innate community spirit. “When we were first building the house, our neighbor, Sean, sort of materialized without my having to ask and started helping me put the roof on, the trim, stand up a wall. Around the neighborhood, whenever someone is putting up a new place, people just start showing up with their tool belts when it’s time to do the roof. It’s a wonderful community spirit, but unfortunately it’s getting less and less as time goes by.” Dave attributes this to the vast amount of growth in the Waldo County area, not just on their road, where a 12 lot subdivision is going in right next door. The community spirit likely will go on undiminished at Ocean Glimpse Farm, however. As Regina Knight says, “I don’t know if we’ll ever garden on our own. I hope to stick with Ocean Glimpse.

About the author: Jane Lamb is a regular feature writer for The MOF&G.