|

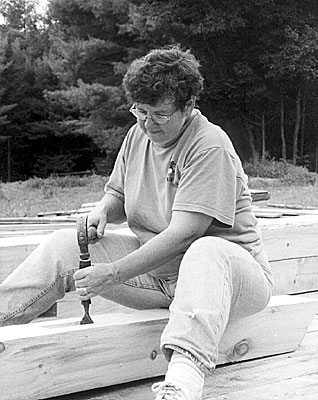

| Mary Ann Haxton holds two handmade pegs in one hand while pointing out the hole where a peg will go. Joyce White photo. |

By Joyce White

Serendipity guided the women at Wrinkle in Thyme Farm in Sumner, Maine, to discover WAgN when they were new farmers and WAgN was a new organization. Marty Elkin and Mary Ann Haxton had gone to the Extension office in Lisbon for information about reclaiming an apple orchard, balsam fir tipping and pasture management.

“That’s how we met Vivianne,” says Haxton. “She gave us a lot of good information but even more important was the encouragement. She already had sheep and a small farm of her own, so was a good role model. She’s very committed to WAgN’s role in serving women farmers, especially small farmers. Many people have no concept of successful working farms with only 30 acres.”

Elkin explains that she and Haxton both had grown children and had left marriages when they formed a partnership 15 years ago. They bought the 30-acre farm in 1995 in the small western Maine town of Sumner, but “the farming piece wasn’t part of the original plan; we just knew we wanted to be in the country. But there was all this old equipment in the barn. They sold us the tractor and left lots of other things – harrow, hay rake, two-horse mower.”

Without the help and support of a lot of people, though – Holmes, MOFGA, their neighbors at Morrill Farm, Daughters of Yarrow – they’re not sure they could have succeeded with the farm. Both had had other careers and neither had any experience with farming.

“The support of other people is so important,” Haxton believes. Now she is the regional organizer for WAgN in western Maine, helping recruit members and organize on-farm tours. She serves as the local link to the statewide network of support for women farmers.

|

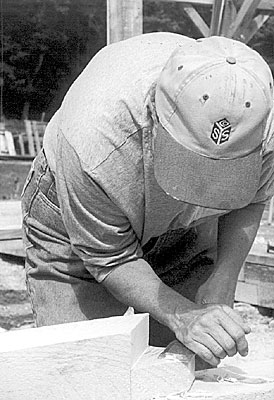

| Marty Elkin uses a hammer and chisel to make a mortise the right size for a tenon … Joyce White photo. |

Getting Started

But before Haxton and Elkin could be much help to anyone else, they had a lot of learning to do themselves about running a small, diversified farm. They’re always in the middle of two or three projects, Elkin says, and each project spawns several related ones.

The maple syrup project, for example, necessitated clearing brush, getting firewood, equipment and a place for boiling the sap, and a bottling system for the syrup. They tap around 175 trees, including some sugar maples of an absentee neighbor who lives in Pennsylvania and is willing to have her land used for something productive. They made 22 gallons of syrup last year. They sell it in small gift bottles and use it for barter.

They now have an old-fashioned collecting tank, offered by someone who switched to collecting sap through tubes. That led to the need for a one-horse dray, which Haxton built from spruce logs from their woodlot to accommodate the tank. They will also use the dray to move firewood. That’s how Bubba, their Belgian work horse, will get his exercise and earn his keep. Haxton learned to use a draft horse at a MOFGA low-impact forestry workshop and a Brattleboro, Vermont, draft horse workshop.

The flock of 10 sheep and one goat earn their keep, too, by cropping grass around the buildings and gardens. The women move their portable fencing frequently so that the sheep and goat always have access to fresh grass.

One of the sheep is a Cotswold, prized for its long, strong, coarse wool fibers. Haxton spins, weaves and knits, and the women are learning to use two types of looms set up in the workroom. They’re trying to upgrade their flock and are breeding for sheep with dark wool, using a dark, purebred Romney. “There’s no guarantee you’ll get dark lambs, though,” Elkin explains.

|

| … while Haxton shaves a little more from a tenon so that it fits into a mortise. Joyce White photo. |

Since they plan to shear just before lambing and don’t want lambing to occur until the weather has warmed, their ewes are bred to lamb in April. Of the three sets of triplets born last spring, two lambs died within a few days. “That was hard,” Elkin says.

In the fall, they sold two lambs for meat. “The boys pay for the grain by becoming freezer meat, and the girls, if we sell any, aim to pay for the hay. The goal is to have the animals self-sustaining,” comments Elkin.

The laying hens provide all the fresh eggs the women can eat, plus some for sale and barter; and their manure is excellent fertilizer once it has been composted. They put the chickens on land where they want to make gardens, to clean up grass, weeds and grubs. After gardens finish in the fall, the hens clean them down to the ground.

“We feed them food scraps, so they come running whenever we go outside,” Elkin notes. They got the hens from the University at Orono, where they were part of a controlled study. Named ISA Browns, they had been in cages and had been handled every day. “It’s nice to have friendly, social chickens, and the grandchildren like them,” Elkin says.

Wrinkle in Thyme’s extensive vegetable and herb gardens were still lush in late September. This was their best year yet for tomatoes, according to Elkin. They canned salsa, tomatoes and green beans and made pesto – learning to make pesto and salsa through barter.

|

| A new batch of tomato juice cools on the cook stove at Wrinkle in Thyme Farm. Joyce White photo. |

More Grains and Connections Coming

The long-term plan is to grow their own grain and corn to supplement local hay, and maybe get a hay cooperative started. They aim for self-sufficiency and local connections, using barter and direct sales, says Haxton. “We want to figure out how to do it all without having it become burdensome. We don’t want it to lose its appeal. We want it to still be fun.” One thing they do in their effort to avoid consumerism is to make all their Christmas gifts.

Both work part time off the farm – Elkin as a nurse lactation specialist and Haxton as a mail carrier – but Haxton hopes to be farming full time within a year and supplementing with carpentry jobs. Another goal is to welcome MOFGA apprentices and/or paying guests to their farm. They also hope to offer workshops every year around seasonal activities, including maple syrup, sheep, haying and gardening.

After a year of planning and preparation and several months of work, their 36- by 48-foot barn is finished except for the big doors. All the animals are inside now. Dan Perron, a neighbor, designed and helped them build their timber frame barn using hand hewn mortise and tenon joinery. Pine for the framing came from their woodlot, and the rest of the lumber came from local sources.

The barn was put together without nails. Using the old mortise and tenon system, the tenon, or peg, is shaped to fit into the mortise, the hole, mostly by slow, painstaking handwork. Haxton explains that the braces have to be inserted into holes in the span beams and the upright posts – that’s how the whole building is held together. They use a drill to get the hole started, but all the finishing – over 300 mortises and tenons – was done with hand chiseling. “You want it to fit snugly,” she says, adding that they got better at it as they worked at it day after day.

|

| Elkin finds a squash among the lush vines in her garden. Joyce White photo. |

In addition to hand tools and people power – four people were needed to lift the span beams into place – Haxton and Elkin used a powered circular saw and electric drill. Perron’s father, Larry Perron of Morrill Bed and Breakfast, used his old Ford tractor with a bucket loader to lift the peaked end frames that were built lying flat, while Dan used his truck to pull them up and Haxton tightened a come-along to ease them into place. Then everyone breathed sighs of relief. Their teamwork and careful measuring and workmanship were succeeding!

Teamwork was essential to getting the barn built and is a key to their whole approach. This farm, still a work in progress, is an example of what can be accomplished by two middle-aged women working as a team with the support of a lot of other people.