|

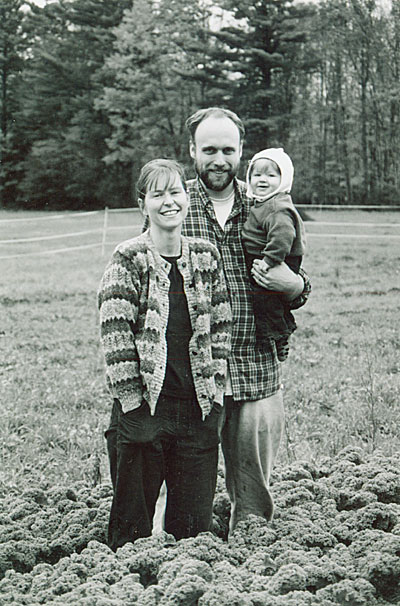

| Amy Sprague, Tom Harms and their daughter, Delia, amidst a lush crop of broccoli at Wolf Pine Farm in Alfred, Maine. As a CSA farm with apprentices, Wolf Pine not only produces food but educates many people, as well. Christine Hull photo. |

by Christine Hull

© 2005. For information about reproducing this article, please contact the author.

The fields of Wolf Pine Farm, where organic vegetables grow, and the share room, where Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members receive their produce, exist symbiotically under the watchful eyes of farm owners Amy Sprague and Tom Harms and in the capable hands of the young staff. Wolf Pine Farm, in Alfred, Maine, proves that the CSA model connects consumers extremely effectively with their food and the farmers who grow it. Furthermore, Wolf Pine proves that youthful idealism, energy and optimism fuel the CSA best. By training and encouraging young apprentices, this CSA invests in the earth and the earth’s future caretakers.

Sprague, 31, and her husband, Harms, 35, own and oversee the 50-acre farm. For Sprague, who comes to organic farming with a background in environmental education, Wolf Pine Farm is her dream. The idea of farming germinated in her mind more than a decade ago on a trip to New Zealand, where she visited an intentional community. “After so many months of feeling discouraged about the state of the world, there was this example that called back to me of something that I connected with-something that I could go home and do.” Returning from her trip abroad, Sprague completed her degree in Environmental Policy and Analysis and became an environmental educator; later she was a farm apprentice in Massachusetts.

Both students at Boston University, Sprague and Harms met while campaigning for a recycling initiative a dozen years ago. As their relationship grew, it became obvious that their commitment to the earth would be an integral part of their life together. When Sprague began to share her dream with Harms, “he didn’t think my idea of doing something in farming was wacky.”

Sprague and Harms’ vision and leadership propel the farm. Harms is an integral part of the life of the farm, but his work as a computer programmer in Lewiston keeps him away for much of the work week. The incongruity of a computer programmer with extensive course work in mathematics identifying himself as a farmer becomes understandable as Harms discusses his passion for the earth, community and sustainable agriculture. He can often be found plowing, harvesting or maintaining the apprentices’ cabin, which he built.

A Map Helps

How did they find Wolf Pine Farm? Sprague laughs and says, “We had this great map! It stretched from southern Maine across the southern parts of New Hampshire and Vermont and included almost all of Massachusetts.” She learned that Wolf Pine was for sale through a classified ad in The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. She recalls their first visit to the farm. “As soon as we saw it, [we knew] it was the best thing we had seen. We drove in and the fields were just right and the sun was just right and everything was very romantic.” In November 2000, they purchased the farm.

These farmers are equally passionate about farming and the CSA model. Sprague identifies five key elements for establishing a successful CSA: experience as a farm apprentice at at least one CSA; time spent at as many farms as possible; desire to establish and operate the CSA as a small business; passion for connecting with CSA members; and a keen sense for marketing. On the last point, she is especially successful. From 2003 to 2004, the farm had a 73% increase in membership; from 2002 to 2004, it had a 550% increase. (When this article was written, in 2004, membership stood at 130.)

|

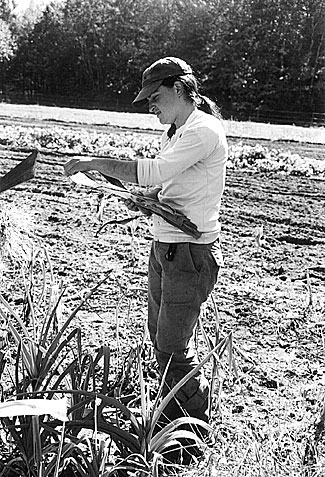

| Rachel Seemar harvests leeks. Seemar appreciates how the CSA model enables customers to connect to the land where their produce is grown. Christine Hull photo. |

A key element of Sprague’s vision for the farm is its apprenticeship program. She and Harms are constantly mindful of their role as hosts to the young staff. They are committed to providing an experience that is full of knowledge for the apprentices. As a former farm apprentice, she has great empathy for the apprentices who share a special time in their lives with the farm. She is aware of the benefits of apprenticeships for both the apprentices and the farm. Farms that hire apprentices are “doing it less for the labor and more for the experience offered to apprentices… It’s my goal to expose people to a lot of the issues that surround organic farming … We’re training people to be spokespeople for the organic movement.”

With the birth of daughter Delia in January 2004, Sprague turned her role as farm manager over to 25-year-old Rachel Seemar. Soft spoken and energetic, Seemar is always on the move. About becoming farm manager, she says, “The offer that Amy was laying out met my needs exactly…We met each other by almost fate at this point in time where we could exactly meet each other’s needs.” When Sprague had her baby, Seemar was looking for more responsibility and hands-on experience than a previous farm apprenticeship had given her.

Sprague says, “Rachel has done a great job of internalizing everything about the farm … When the seedlings were starting out in the greenhouse, Sprague would wake up throughout the night to check on the greenhouse temperature.” Noticing this, Sprague knew she had hired the right person for the job.

Seemar talks excitedly about her experience as a farmer in Massachusetts. “I worked at this farm and it was so hands-on and so tactile. I felt like, yes, this piece of land is being cared for in an amazing way.” This enthusiasm for sustainable agriculture that she experienced years ago is still apparent as she takes on the seemingly endless tasks of farm manager.

With days that begin at 6 a.m. and often end 12 to 14 hours later, Seemar’s dedication to Wolf Pine Farm is unwavering. One senses that without true dedication to the larger goals of the farm, these long days would be unbearable.

Walking from the farmhouse to the share room in the barn, Seemar smiles as she sees two young boys with their mouths stuffed full of cherry tomatoes. When asked if they are enjoying the tomatoes, the boys can only nod their heads as their mouths are too packed for speaking, and she chuckles. “That’s why this place is important,” she says. She is attracted to the CSA model because it’s an opportunity for children (and adults) to authentically glimpse farm life and connect to the land that grows their produce. Although often moving from one urgent task to another, she always has time to answer questions in the share room.

|

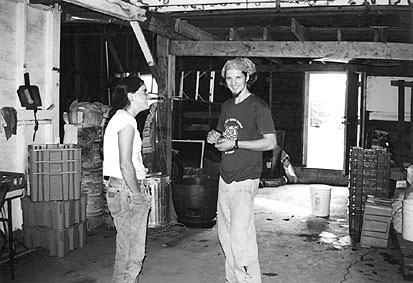

| Farm manager Rachel Seemar and apprentice Steve Nelson share a laugh in the barn. Christine Hull photo. |

Seemar and her staff obviously work well together. She has an easy rapport with apprentices Steve Nelson and Andy Melson, who look to her for guidance. When talking about her fellow farmers, Seemar smiles and says, “All of us have a desire to listen and communicate with each other. Steve and Andy are willing to ask questions and to learn and to listen, and they’re just fun, too – they have great senses of humor – and they’re hard working. They have a broader vision of what’s going on here.”

Lessons for the Rest of Life

Nelson, 24, is laid-back, gregarious, and has an easy smile. He comes to farming with a background in mechanical engineering and with coursework in sustainable agriculture. He encapsulates his experience as a farm apprentice by saying, “I’ve really grown to like the long days.” He’s satisfied to learn how much he and his fellow farmers can accomplish in a day. The hundreds of onions drying in the barn loft “give me such a sense of what I can do.”

“If somebody told me they worked on a farm before, I wouldn’t really give it that much weight, but now that I’ve been here all summer, I realize how much this teaches me about time management,” Nelson says. He tells of how, as a new apprentice, he wanted to attack every weed in the beds. Under Seemar’s tutelage, he quickly came to appreciate the importance of prioritizing and learned that attacking every weed was impossible, because of pressing matters and limited hours. He envisions pursuing his interest in permaculture after his tenure at Wolf Pine and is confident that the time management skills he has obtained will serve him well in many future endeavors. Sprague concurs. “Life skills are learned here that you take with you forever.”

|

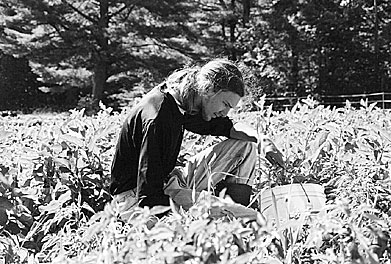

| Apprentice Andy Melson harvests peppers. The job seems far from his training (he has a degree in music theory), but satisfies the need he felt for a “big change from student life.” Christine Hull photo. |

Melson, 22, is thoughtful, reserved and amiable. An accomplished violinist with a Bachelor’s degree in music theory, he made the jump to farming because “I wanted a big change from student life.” The apprenticeship has provided just that. “Breadth is the reason I came here,” he continues. “Also, I am concerned with … social issues-issues about control of natural resources and corporate control of food production and also the healthy appeal of the outdoors.” He foresees becoming, possibly, a professor of music or history, and believes his stint as a farmer will help. “I would like to have lots of experiences outside of my particular field. I respect teachers and professors who have this. I think it adds a lot of depth and weight to what they say.”

Melson touches on the sense of optimism that abounds at Wolf Pine Farm: “The fact that Tom and Amy are climbing out of the hole (of debt) is very hopeful, because it means that not all food must come from afar in order to be economically viable. To my way of thinking, that’s the most important thing about this farm – that it can actually work.”

Although most apprentices stay with the farm for only one or two seasons, their contributions have a lasting effect on the land. They know that the measures they take to support sustainable agriculture this season will allow for bountiful crops in years to come. Their collective, firm commitment to the earth is summarized by Seemar: “I really want my life to be the least impactful on the earth … I want what I put my time and energy into to be a positive cause and to be something that is leading towards social change. I’m not so content with the mainstream-status quo-of our society. It seems very self-centered and not forward thinking.” Looking to the future of sustainable agriculture, Seemar says, “We’re not thinking about how we impact each other. It seems like sustainable agriculture has so many possibilities for more than just growing food.”

Sprague and Harms infuse the room with energy when they talk about the future of Wolf Pine Farm. “We like to think in terms of a five-year plan,” Harms says. “My mind goes in fun and interesting directions,” Sprague adds. They nearly interrupt each other as they hurry to share their vision for the farm, which includes increasing the number of CSA shares to possibly 275, cultivating an additional 1 to 2 acres of vegetables (for a total of 6 to 7 acres), owning animals, and offering educational opportunities for children. Sprague says that Wolf Pine Farm’s first four years focused on learning the “A” and only dabbling in the “C” of the CSA. Harms concurs. “We’re both quite fired up about what the ‘C’ in CSA can become.”

About the author: Christine Hull is a freelance writer who lives in York County.