|

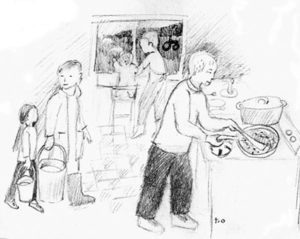

| Toki Oshima drawing. |

By Grace Oedel

My husband and I recently moved in with my in-laws with the intention of farming family land. I wish I could say this was a smooth, easy process, but we all struggled. We were unused to what it meant to live together. We had differing expectations about how to communicate, how to spend time together, how to tend the land, how to live.

Family and farming have gone hand in hand for centuries, but increasingly young people are entering agriculture as individuals or couples. While many people do not have biological family on whom they can rely for any number of reasons, I imagine “family” broadly, meaning something like “deep, committed community” – intimate and long-term. Perhaps we have chosen our families, or adopted someone else’s family. Whatever permutation of family shape, coming back into deep community with others helps form a foundation for resilient farm life.

Many young people who want to farm don’t have the finances to purchase their own piece of land. A couple of our friends are renting an old farmhouse together with their parents and working the land around it. Another moved into a grandmother’s house after she died and are living with adult siblings to pay the mortgage and avoid losing the farm to developers. Others are forming co-ops with old friends. Land is expensive – pooling resources makes sense.

Living inter-generationally offers solutions to issues beyond finances. Child care, for example, is a perennial struggle for farmers. Child-rearing years and farming years overlap. Having sufficient energy to raise children, run a home, tend a farm and market products requires more than two people. The same applies to growing older; as folks age and need more support in their lives, living in community makes sense.

And yet despite all the reasons living with family makes sense, it proves incredibly challenging. Depending on others feels bewildering, both financially and culturally. It’s embarrassing to talk about money or to ask for help; it’s challenging to expect others to show up for you and to hold yourself accountable to do the same for them.

Why is it so hard when it makes so much sense? First, we’re simply out of practice navigating multi-layered relationships. We are used to compartmentalizing our relationships: babysitter who watches the kids, landlord who owns the house, farmer who leases the land. A lot of our relationships are defined by a flow of money; we exchange capital and expect services in return. Living in community forces us out of money-focused relationships into more intimate conversations about our deeper needs.

Furthermore, we often fall back on old patterns of interacting that don’t serve. (I imagine this happens more with biological family, although any old relationship likely contains outdated patterns of interacting.) It’s challenging for both parents and children to see each other for who they are now as opposed to who they were when last they lived together.

Further, it takes real effort to share our vulnerabilities by speaking our needs – and to listen to others’. Difficult to really trust other people enough to count on them to be in our “family,” whatever shape family takes. Finally, it proves a delicate edge to walk between independence and interdependence. Americans are used to depending on themselves (and some measure of individuality is certainly important), and it is intense to feel so deeply intertwined with the needs and expectations of others – which you may or may not share.

I don’t think we can just teach ourselves how to do this. Luckily, supports are available to help us. Organizations like Land for Good facilitate conversations for families about farm transfer. Nonviolent communication (a process of open communication) helps put charged emotion into straightforward language. Intentional communities offer a path for people who want deep community with people who share a similar vision.

Our family struggled in our personal process of living together. But as a result, our relationships have deepened. We have worked to articulate to each other our needs, our visions, the ways in which we are willing to compromise. We have learned to appreciate each person’s unique communication style and gifts.

But what has nourished the relationships most is our consistent showing up for each other. Our parents care for the animals when we go away; we shovel snow for them to get to their woodpile; we cook each other dinner. We make our interconnection plain by showing up in quotidian moments. With each small act, we demonstrate that we are deeply for and with each other. We certainly continue to struggle. But we also get recharged in our daily sharing of effort, and believe that together we are growing something much stronger than what we could alone.

About the author: Grace Oedel runs an educational farm in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, Dig In Farm, with her husband, Jacob Holzberg-Pill. Dig In Farm’s first project is Spiral, a residential summer permaculture program for young women: www.diginfarm.com/spiral.