|

| Jim Nichols with his parents, Lois and Nick, who launched him on a grounded, farm-oriented life. English photo. |

By Jean English

Lois and Mahlon “Nick” Nichols raised five children (one now a MOFGA certified organic grower, Jim Nichols) on a Dewitt, Michigan, farm. During a recent visit to Maine, they talked to The MOF&G about the difficulties and rewards of the farming life they began more than 60 years ago. Many current MOFGA growers may see parallels.

Nick was born on his parents’ Michigan farm; Lois was born and raised in nearby St. Johns. They went to high school together but didn’t know each other “because he was country and I was town,” said Lois.

At 17 Nick enlisted in the Navy, served on a battleship in the South Pacific, and later watched from the deck of the Battleship Idaho the Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Harbor. Lois and Nick met and married after the war and, in 1952, moved to their own 40 acres and started farming.

Family Farming and More

Most of the farmers around Dewitt and St. Johns also worked in factories or in town. “If you lived within 30 miles of Lansing, you worked at the factory,” said Nick. He later worked at Sears, Roebuck for 33 years in order to have medical insurance, retirement and other benefits.

“You could not make a living off a small farm at that time,” said Lois. Even now, many area farmers work off the farm to get health insurance.

|

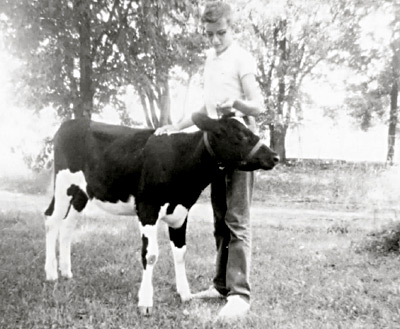

| Jim with his cow, Popcorn, in 1963. |

Jim described their farm in the ‘50s and ‘60s as mixed agriculture, including 4-H activities, some cattle, pigs, a milk cow.

They always raised chickens and a vegetable garden, added Lois, slaughtering poultry on the farm for themselves and to sell directly to customers.

Lois canned all the tomatoes and other produce she could use; filled their 20-cubic-foot freezer; and made jams, jellies and juice from the farm’s grapes.

“That’s one thing about a farm,” said Lois. “You always have enough to eat.

“Eventually,” said Lois, “we bought the family farm” across the road, which Nick’s father had bought in 1915. With 132 acres, they then raised corn, soybeans and wheat. This was before the term “organic” was being used, but by rotating their crops with animals, they minimized pesticide use.

They also raised cucumbers for a local pickle factory and hired first Mexicans and later Texans, who came with their families to hand-harvest. “It was very hard work for those people,” said Lois, “but it did get them out of the heat. I was amazed how they would work all day long in that field and then come in, have their meals, and then they would sit out there and laugh and talk; the children would play. You would think they would be so tired … but they were happy people. We had a good association with them.”

“We started harvesting in July, and by the end of August we were all done,” said Nick.

“It was a quick cash crop for us,” said Lois.

|

| The farmhouse where Mahlon and Lois Nichols raised their family. Photo courtesy of the Nichols family. |

Lois also sold fresh eggs. “I had to candle them, weigh them. They wouldn’t allow you to do that today, probably. I pick an egg up today and hold it – it’s supposed to be large. I don’t think it’s a large egg!”

Regarding support for farmers, Lois said Grange suppers helped with the sense of community. Nick said the Ladies’ Aid Society created community when he was young.

Also, “our whole family lived around us,” said Lois. “There was always someone who would help.”

Lois got involved in 4-H with the children. When the kids were a little older, she drove a school bus and later worked as a prep cook.

Until high school, the children walked 1-1/8 miles to the same one-room schoolhouse Nick and his siblings had attended. Jim and his classmates carried lunch buckets and cold lunches until the mothers began bringing more appetizing fare to the school. Lois recalled that one day the teacher asked all the children to bring a can of soup. “She dumped it all together. When they came home, they raved about it!”

When not in school or helping on the farm, the kids played in the nearby woods. “I never worried about them,” said Lois. “We didn’t jump in the car and run to town with them. The 4-H club had leaders right in the community. They would go to the homes in the evening and do their sewing or woodworking.”

|

| Jim today, selling MOFGA certified organic produce from his Gander Gardens at the Bucksport Farmers’ Market. Photo by William Nichols. |

“The wheat harvest was a big deal,” said Jim. Nick explained that he, his two brothers and his father would combine the wheat at his farm, then move on to one another’s farm. They stored the grain in their two-story, four-bin granary, and when the price was right, they brought it to grain elevators that were usually community-owned. From there it was loaded onto boxcars.

Lois recalled the first time she experienced the extended family arriving to combine. “My father-in-law brought me over a big roast, and I had two children, and I was still young; I didn’t even know what to do with it! I didn’t have a pan big enough to put it in! So I went over to my mother-in-law’s and said, ‘Help me or tell me what to do.’ She was a great help to me … a kind farmwoman. She told me one time [after Lois and Nick had lost some farm animals], ‘You know that happens, but you go on.’”

Asked if she ever felt overwhelmed, Lois answered, “Yes!”

And asked how they got through difficult times, Nick said, “We just did.” Lois added,

“You just had to. There were times when I didn’t think there were enough hours in the day to do everything.”

They had to do a little more than just “go on” during the late ’70s. Nick said the USDA had encouraged all farmers to plant all the wheat they could, to sell to Russia. “Then, once we got it planted, they stopped selling it to Russia” (due to the Russian invasion of Afghanistan). At the same time, interest payment calculations on farm loans changed. Farmers had been able to borrow money for fertilizer and other inputs at a relatively low, fixed rate for three to six months. Those payments changed to floating rates in the late ‘70s, “so at the end of 90 days, what you couldn’t pay, instead of just renewing it, the interest went up. We went from 5 percent to 16 percent. That’s when we drove the tractors in the tractorcade.”

|

| Tractor convoy heads to Washington, D.C., Feb. 1979. Photo by J. Wooten, courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, image # 79-1709-17. https://siarchives.si.edu/. Used with permission. |

The Tractorcades

The American Agricultural Movement organized tractorcades in the winters of 1978 and 1979 – thousands of “farmers helping farmers,” said Nick, driving their tractors, sometimes thousands of miles, to Washington, D.C., to protest the fact that their input costs exceeded prices paid for their crops.

“From our county,” said Nick, “around 15 tractors left in a snowstorm. One of the men had a motor home; that was our kitchen. A dairyman donated milk for the trip. Oil companies donated oil. We had a tractor with a wagon, [with] 500 gallons of diesel on it.” They went from Michigan to Ohio, West Virginia, Maryland and then Washington, D.C.

“When we left Wheeling [W. Virginia], within an hour there was a terrific snowstorm,” so the farmers were unable to get to their planned destination that night.

“We’d stopped at a highway rest stop.” The county sheriff came along and said, ‘You can’t stay here tonight.’”

He guided them to Frostburg, Maryland, riding “right down into town, and they took us into the college – a small, small college – and we had 1,500 tractors. We filled the college parking lot, and the police had arranged for the residents to let us park in their driveways. We got up in the morning, we had a chill index of 50 below zero. I said, ‘We can’t start those diesels in that weather.’” The sheriff said they had to.

So they did, but the hill out of town was now ice-covered. The sheriff had the hill sanded and “we got out of Frostburg,” said Nick, “onto Highway 70 to Frederick, Maryland; in an hour we were driving tractors, with no coats on.”

Lois, then working in a St. Johns restaurant, recalls that some women came in and talked about “those tractors … all blocking the highway.”

|

“Do you ever think people understand farming?” asked Lois.

Not always. Nick said the farmers were seeking parity (getting at least break-even prices for their crops). “We were in the [USDA] building in Washington, D.C., and the elevator operator said, ‘I wish you’d hurry up and get your pear tree.’”

When the tractorcade was approaching the USDA building, the police ordered the farmers to park on the National Mall.

Nick said, “Wait a minute, you’ve got irrigation on it don’t you?”

“Ya,” the officer replied.

“I said, ‘Well, these tractors will tear it up.’”

“Oh they won’t hurt us,” said the officer.

Two days later, nationwide newspapers announced, ‘Farmers in Washington Tear Up the Park.’

Lois stopped trying to explain the tractorcade to people. They “just take it for granted: The food is there. They don’t know the work involved. Even today, even with modern equipment.”

Public sentiment about the tractorcade turned positive when a snowstorm hit D.C., said Nick. “We were going out and picking up doctors and nurses and taking them to hospitals by tractor. We’d load kids into the wagons and take them around the White House. A lot of them had never seen anything related to a farm. They were poor. They looked after our tractors – nobody would mess with them.”

The American Agricultural Movement continues to seek fair prices for and fair treatment of farmers. (See https://www.aaminc.org/history.htm)

Worldwide Connections

As their children grew, the Nichols family hosted exchange students from Germany, Japan, Argentina and Venezuela. “I wanted the children to know that there were other people outside of our own small community,” said Lois. Those relationships lasted; the Nichols’ grandchildren have visited the former exchange students in Germany.

Jim’s sisters Kathy and Joanne were exchange students in Japan. A grandson now speaks fluent Japanese, was a Fulbright scholar in Japan and currently teaches English there.

Jim also caught the travel bug. “When he was 18,” Nick said, “he wanted to take off. Finally we said he could go to Germany, stay with Hans [their former exchange student]. So he bought a ticket to Sweden, hitchhiked up across the Arctic Circle into Finland, back down to Denmark, went to Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, Greece and then Egypt, down the Nile River to Aswan. He went the first of October and promised us he’d be home for Christmas. The week before Christmas we got a phone call from him: He’d just left for Egypt. He spent a night with Turkish soldiers in Cyprus. Then he went to Israel. We got a letter from him – he was picking bananas in the Golan Heights. There was fighting in the Golan Heights. We called the kibbutz and asked him, ‘When are you coming home?’ He didn’t have enough money [with him] to get out of Israel.” So Nick got him a plane ticket to leave Israel, “and the next I knew he was in Yugoslavia and then Germany, and then he flew home. He was gone six months. He spent about $1,300.”

“He did a lot of walking,” said Lois.

Jim’s explanation: “As a kid I read National Geographic a lot.”

“In 1945,” said Nick, “when I was in combat, I never thought my children would be going to Japan, Germany.”

Today’s Farm Scene

In 1952, a big farm was 150 acres, said Lois. Now there’s an 8,000-acre farm in their area, and “Lansing is creeping out on us.”

Nick noted that farming has changed since Monsanto developed patented corn and soy seed. “Where the seed would probably [have] run us $20 a bushel, now it’s $100 a bushel. And you plant them, you have to sell back to the factory. You can’t replant them. I don’t believe in that. As far as I’m concerned, I bought it, it’s mine.” He laments that Monsanto “owns the world today.”

Nick said that 1,000-cow Dutch dairy farms are taking over where 30- to 50-cow herds once thrived. “The soil cannot absorb that,” he said. “The waste has to go back on the farm, and if you try to put it on 40 acres from 1,000 cows, you destroy the land.”

Lois noted the increased price of farmland as “the big farmers come in, and they’ll up the price” to rent the land – a price the smaller, local farmers can’t afford. Developers are also buying up land.

Lois believes that diversifying is one key to success. One of their nephews raises pheasant and bird dogs, and people come from town to hunt on the farm.

Also, “a lot of horse people are coming in,” said Lois. And “about 60, 70 miles north, there are a lot of dairy farmers, but they’re fourth generation, some of them.”

Continuing the Farm Influence

The Nichols’ influence over their children has persisted. “Jim has a huge garden now,” said Lois, “and we have a younger son – you can’t take the farmer out of him: He has 9 acres, four goats, some chickens.”

Jim came to Maine on a boatbuilding internship with Maine Maritime Museum. The area reminded him of family vacations in Minnesota – hearing loons on the lake, being in the woodlands and by the water – so he stayed.

In Maine, Jim worked as a house carpenter and still does some of that but focuses on his 1-1/2-acre Gander Gardens at Sandy Point, selling at the Bucksport Farmers’ Market and from a stand at his house. His hoophouse, funded partially by NRCS, produces “the tomatoes I ate as a boy,” said Nick. Jim grows other vegetables, herbs, cut flowers and wheat, and has sold to MacLeod’s, the Good Kettle restaurants and the Belfast Co-op.

Jim thinks growing up on a farm may cultivate an entrepreneurial spirit. His sister Kathy, when working as a guidance counselor, told kids, “Believe in yourself. Do not sell yourself short.”

His sister Joanna, while counseling abused women in Bosnia and Croatia, started running marathons to raise money to get a 13-year-old girl out of a refugee camp. Now the former refugee works for a pharmaceutical company and her sister just got her engineering degree. Joanna’s nonprofit Jericho Foundation continues to do relief work in Bosnia.

His brother Michael is a self-taught engineer and entrepreneur. He is a licensed professional diver who came to Maine and taught Jim’s two sons how to dive.

Similar to Jim, Scott strives to continue the independence he learned on the farm through gardening, maintaining his beehives, pressing cider and making cheese.

Lois, who has read many MOF&G stories about Maine organic farmers, said, “I give couples on small farms here a lot of credit. It’s hard, but they all look like they’re happy, and that’s what counts. I think we just have to shut out the outside world a little.”

While the extended Nichols family helped each other a generation ago, Jim thinks MOFGA helps provide community in Maine now. “A lot of the resources I’ve used have come from MOFGA,” said Jim. “If MOFGA hadn’t been doing it, all I would have would be a corporate model to turn to. From MOFGA, you know that someone else has done it, so you’re going to try it, too.”