|

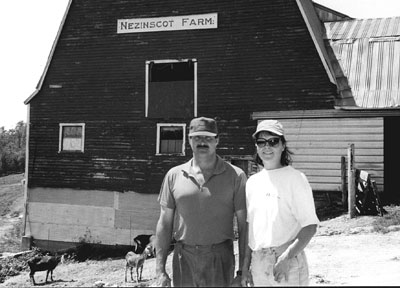

| Gloria and her husband, Gregg, raise many animals – including almost 50 organic milk cows. “Our goal is a totally organic herd,” says Gregg. Jane Lamb photo. |

By Jane Lamb

It’s one thing for back-to-the-landers to come to Maine to start a new life, as many of MOFGA’s founders did more than 25 years ago. It’s quite another for people with deep roots in Maine agriculture to prove that organic methods can also save grandfather’s farm. MOFGA’s original vision – to promote sustainable, healthful agriculture as a viable lifestyle – seems to have come full circle. As MOFGA moves into its new home and a new millennium, this is one more cause for celebration at the landmark 1998 Common Ground Fair, I reflected, after an inspiring morning last June in central Maine.

Cresting the hill on Route 117, a mile east of Turner village, the first thing that struck my eye was a big, old fashioned dairy barn – not looking neglected, no “For Sale” sign. Next I spotted a field full of cows. “Wow! Real cows, a real farm!” was my first joyous reaction. Cows have become a rare sight on Maine byways, where once there were ample playing pieces for roadside cribbage. They seem more endangered than ever by recent reports of consumer whining and congressional muttering about “unfair” price supports for New England dairy farmers.

Across the road from the barn, between a lush vegetable garden and a neat building marked Nezinscot Farm Store, a schoolbus was disgorging a flock of children for a farm tour. A front-end loader lumbered past the barn on some appointed errand. The woman I was looking for, Gloria Varney, climbed over the bank dragging a hundred feet of green garden hose. “Follow me,” she tossed over her shoulder and promptly disappeared around a comer.

|

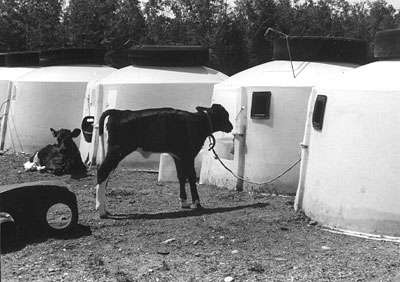

| Hutches give calves enough room to run around, and the penetrating sun keeps the animals warm and dry. The hutches also cut down on the spread of disease. Jane Lamb photo. |

“She’ll be right back,” her husband, Gregg, reassured me, taking a break from stowing hay silage. Gloria is hard to keep up – no question! Though he pleaded no time to talk, Gregg couldn’t resist adding that without Gloria’s multifaceted contributions, Nezinscot Farm’s 100-head dairy operation couldn’t survive. “It’s the only way we’ve managed to hold our own,” he said. “When we got married in 1987, all I had was dairy cows. Then Gloria started the smaller animals – sheep, goats, turkeys, ducks, chickens. They’re really more profitable animals [than cows].”

Diversification Is the Answer

“That’s when the diversification of the farm started,” Gregg continued. “Selling raw milk as well as pasteurized, [selling] milk products, opening the store, selling meat and wool. That’s what keeps us in business.” Gregg manages the dairy side of the operation, with its unique split herd of close to 60 “conventional” cows and 40 organic cows, as well as the 200 acres in corn and 300 acres in grass that feeds them. Except for the conventional herd (which the Varneys are gradually phasing out) and the free-range poultry, the entire farm and its products are MOFGA-certified.

Nezinscot Farm, on the Nezinscot River midway between Turner Village and Turner Center, has been in Gregg’s family for three generations. His grandfather owned it originally, and his father took over in the late 1940s. His parents went out of the dairy business with the dairy buyout in 1985 and were leasing the bam to an embryo transplant operation when, in 1987, Gregg bought the farm.

|

| Gloria Varney has brought diversification and value-added products to Nezinscot Farm to help the dairy farm remain a successful enterprise. Jane Lamb photo. |

Farming In the Blood

If Gregg felt compelled to continue the family farming tradition, Gloria had the same need. Settling in the shade of a picnic table umbrella, she continued relating the farm’s promising story. Gloria grew up on a sustainable farm in Livermore, one of 10 children of Francis and Alice Castonguay. “We always had a large garden that supplied our own food year round,” she begins. She graduated from the University of Maine in Farmington in 1988 with a degree in community health education and nutrition. “I worked off the farm for a year, and realized I wanted to be back on the farm, doing something,” she says. She had met Gregg when she was a junior at Farmington. He was running the farm and bringing animals to her parents’ custom slaughterhouse in Livermore. When Gloria moved to the farm with Gregg, she decided she didn’t want to be just a dairy farmer. “My philosophy had always been that in farming, you either get big, get out, or diversify and stay in at a medium size.” She began researching diversification in the farming context. “Basically, I started with what I enjoyed doing, which was crafts, at the time with wool,” she says. When an Auburn yarn shop, her main supply source, went out of business, she bought them out and started selling yarn from the farm. “I saw a need for that kind of wool supply in the central Maine area because the next nearest place was Portland.”

Meanwhile, Gloria was raising some of her own animals and a small garden. “My yarn customers started showing an interest in meat back in 1989 and ’90. That’s when I got the idea for a farm store that featured a little bit of everything. I opened a small shop in the kitchen, initially. I looked into organic certification because of consumer interest. Actually we were farming organically anyway. The land had been chemical-free since 1960. And it’s grown from there.”

Getting people closer to the source of the food they eat is one of Gloria’s goals. She offers a full range of organic vegetables, meats, milk and other dairy products, along with home-baked breads, home-canned relishes, pickles and jams and frozen meals, all produced at Nezinscot Farm, as well as organic teas and spices, cosmetics., yarns, knitted and woven items and more. She goes to farmers’ markets in Auburn, Winthrop and Farmington, helped by a young woman during school vacation. What she doesn’t sell is processed into value-added products. Organic milk is sold in the store and, along with bread, is wholesaled to a few stores that pick it up at the farm.

Value Added: The Way to Go

“Diversification is what saved us,” Gloria points out. “This farm could never keep going on just dairy with wholesale prices. When they tell you it costs $15 to make a hundredweight of milk and you get paid $13 or less, it’s not long before the farm starts going backward. It takes two incomes, whether one spouse works off the farm and brings in income, or stays on the farm and starts doing something there. This is just my part of what I bring to the farm. Value-added is what brings the best income.” Gloria adds to the value of milk from cows and goats in her 15 x 13 state-licensed cheese plant where she produces cheddar – plain and smoked, soft cheeses, feta and chevre blends. Her eight goats – Nubians, Alpines and Toggenbergs, each produce about a gallon a day. All their meats – beef, veal, pork, lamb – are organically certified. Chickens, ducks and turkeys are the exception, but as free-range birds they get a 30% grass diet supplemented by hormone-free commercial grain. Animals are commercially slaughtered. Older customers are delighted to find stewing chickens – mature roosters – and oxtails, no longer seen in supermarkets. “They want a stew like their grandmother used to make,” Gloria explains. The meat is packaged and sold frozen, directly from the farm. Value is added to the meats as well, in the form of ‘frozen dinner entrees as shepherd’s pies, stews, turkey and beef enchiladas and lasagna. “People can pick them up, take them home and put them in the oven frozen to bake,” says Gloria. In addition, customers can order custom sandwiches to eat at a small table in the store, at a picnic table outside, or take home. Soups, chowders and quiches are also on the eat-in or take-out menu.

Gloria gets up at five in the morning to start baking and by eight o’clock, 40 or 50 loaves of bread in half a dozen nutritious variations are being packaged by Gloria’s full-time store helper, Joanne Blue, or are about to come out of the 18-loaf convection oven or the 10-loaf gas oven. Joanne also keeps an eye on Mackenzie, a year old this month, the Varney’s youngest girl while Natasha, seven-and-a-half, and Samantha, six, are at school. Gloria spends much of her summer time with her animals, in the vegetable garden and marketing.

Fitting It All In

“I do a little bit of a lot,” Gloria says, describing her active life. “The key is finding ways to simplify my tasks. I’ve spent maybe two hours in the vegetable garden so far this year.” The miracle of thriving, weedless stands of garlic, greens, peas and beans is accomplished by the uncomplicated method of sowing clover between all the rows. Gloria keeps it to a reasonable height with a quick pass of the weed-whacker. The thick green clover mulch keeps soil moisture at a level that doesn’t require irrigation. An overhead sprinkler system is in place, just in case. Gloria uses it occasionally when plants are first set out, but once the clover comes up, she rarely needs to water, even in a really dry summer. She has about an acre under cultivation, which includes the established roadside bed and one she’s developing at the back. Another acre of sweet corn and squash grows down by Gregg’s silage corn field. A greenhouse, under construction, will provide fresh greens throughout the winter. Half is floored with a cement pad, the other half is planted to oats to build up the soil and get rid of weeds. She’ll plant greens directly in the ground and run some animals, probably chickens, on the cement side to help heat the greenhouse in winter.

The Nezinscot broiler flock is mostly Rhode Island Reds. The girls had fun picking out different breeds for the next flock of layers, which of course had to include some “rainbow chickens” as they call Araucanas, for their green eggs. Gloria raises and markets about 300 turkeys every season as well. Her flock of sheep includes 20 ewes – Corriedale, Romney and Lincoln crosses – and pure Cotswolds and Corriedales. She markets lambs for meat and sends fleeces to Green Mountain Spinnery in Vermont. “I get my own wool back in three-ounce skeins. It doesn’t get blended with anyone else’s. It makes a good knitting blend, says Gloria. Some of the better fleeces go to the Ohio Valley, where the wool gets carded, washed, picked and put into roving for spinning. Gloria and a couple of other ladies who like to knit in the wintertime make socks, mittens, hats and vests, a few sweaters, but mainly smaller items that work up quickly to meet customer demand. They also do some weaving and felting. “We try to do as much as we can with what we’ve got, she says.

And CSA, Too

Nezinscot Farm runs its own version of Community Supported Agriculture, as well. “Typically,” says Gloria, “CSA members get a bag of whatever is allotted them every week. Ours is different. People buy a share and get to use it on anything we make or produce here, year round. If some weeks they just want some beef, or some vegetables, they can get that. It’s appealing because they get to choose, rather than in the spring getting a big bag of greens they can’t use up, and that’s all. They can get bread, milk, butter, cheese. They can join any time of the year. This year we have about 20 people signed up.”

Though it would hardly seem necessary, Gloria also has an exercise program. “People laugh, but I’m a firm believer in an hour of play every day and I make sure I get out either for a walk or a run, or ride the horse. Normally, the girls get on their bikes, I put the youngest in a buggy and off we go for about three miles a day.”

Making Dairying Work in Maine

“There are a lot of dairy farmers in the Turner area, and they’re stuck,” says Gloria. “The average farmer is in his mid- to late 60s or 70s. They’re too old to start diversifying or try something else and they can’t afford to get out. The children are gone. They don’t want anything to do with farming.” Gregg and Gloria have found a way to work dairying into the diversified organic farming mix that so far has kept them ahead of the disastrous, below-production-cost, wholesale price of milk. Even though organic grain costs $3 20 a ton compared with $180 a ton for commercial grain, Gregg figures going entirely organic will pay off in the long run. One advantage is that organic milk sells for a predictable $20 a hundredweight, while the commercial price fluctuates between $12 and $16. “You always know what your milk check will be. It makes financial planning a lot easier,” he says. All the organically-produced milk that isn’t sold in the store or used for cheese goes to Stonyfield Farm yogurt producers in Londonderry, New Hampshire. The conventionally-produced milk is sold to AgriMark.

Managing a Split Dairy Herd

The Varneys have been MOFGA members since they became certified growers six years ago. They were the first producers of organic milk in the state; now there are about twenty. Their two dairy herds, one conventional and one organic, differ not only in the way they are managed, but in composition. The 54-head conventional herd are all black and white Holsteins or red Holsteins. They have a pasture-size exercise paddock where they graze and get additional hay when the grass gets low. After morning and before evening milkings, they go in and out of the bam at will to get their feed of grain. The 45-head organic herd, half Jerseys, a quarter Holsteins, and a quarter Jersey-Holstein crosses, go out to pasture for 10 hours a day. When they return to the barn for evening milking, they get some hay and corn silage and organic grain. Unlike the conventional cows with their one big paddock, the organic cows are grazed intensively on a series of four lanes in succession, rotating about once a week.

Except for the fact that they get non-organic grain and can be treated with antibiotics if necessary, the conventional cows enjoy most of the same perks as the organic ones. All their pasture and silage is organic. “If an organic cow gets sick and we can’t cure her homeopathically, she goes into the conventional herd, where we can treat her with antibiotics,” Gloria explains. “She stays there for the rest of her life.”

Nezinscot beef cattle – black- and white-face Holstein-Hereford crosses and Limousines – stay in their own pasture around the clock in seasonable weather. Veal calves are raised on their mothers until they’re “of size.” All the heifer calves are raised for dairy replacement in curious little white plastic, pill-box-shaped shelters called calf hutches. Ten feet wide and 51/2 feet high, each is like a little greenhouse, Gloria says.

“The calves aren’t tethered or restricted in any way. They have enough room to run around and the sun penetrates through and keeps them warm and dry. They’re great. If a calf gets sick, it doesn’t spread disease to others.” Calves are usually born in the early spring or early fall and are taken off their mothers in a couple of days, to be bottle fed when the mother returns to the dairy herd. They remain in the hutches for two-and-a-half to three months, tethered outside the open doors if the weather gets too warm. The few summer-born calves aren’t usually put in the hutches.

Organic Farming Works

Gloria and Gregg Varney are well on the way to proving the advantages, economical as well as philosophical, of organic farming over conventional. Like Peter Bondeson in New Sweden moving from conventional to organic potato production (The MOF&G, December, 1997), they are phasing out their conventional dairy herd on a schedule. A year ago they had 25 organic milkers. Now they have nearly doubled that number. “Our goal is a totally organic herd,” says Gregg. “The most important part of the farm is our land,” he continues, warming with pride. “The 75-acre intervale runs for over a mile along the river. That’s one of the first reasons we started to go organic. Everything is close to the water. We don’t have to use any chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, hormones. The river was there [maintaining a water table that requires no irrigation] and we just started cultivating, using our own manures. We’re just awfully pleased with the way our land looks.” The perennial attraction of lush green river bottom is undeniable; an archeological dig on the bank is uncovering evidence of a 10,000-year-old culture!

For Gloria, the ever-growing diversity and the ability to find a market for every new thing the farm produces are exciting. “When you get to retail so many products, and have customers appreciate it, it means a lot,” she says. “It’s nice to see people coming to the farm to get their food.”

About the author: Jane Lamb, formerly of Brunswick, Maine, is now retired in California.