|

| Paula and Sumner of Meadowsweet Farm in Swanville. Lamb photo. |

By Jane Lamb

Raising animals on fresh green grass is vital to Paula and Sumner Roberts at their Meadowsweet Farm in Swanville. Their philosophy is to “treat all animals with respect and allow them the fullest expression of their natures consistent with good husbandry… [This] includes freedom of movement, exposure to sunlight and fresh air, clean surroundings, a normal social environment, and food suited to their digestive systems. For sheep and cattle this means a grass diet with no animal by-products or added hormones, for chickens a mix of grain and free selection of green grass and bugs.”

Sumner grew up in Upstate New York dairy country, though not on a farm. His parents had a big organic garden and horses. The family moved to Camden when he was 12, and he spent a lot more time with boats than agriculture. Paula grew up in semi-rural Massachusetts and always had horses. She has a background in art and a master’s degree in environmental education, which she has taught in a lot of different settings, lately as science in Maine schools. She’s organizing a farm day camp for eight- to 12-year-old kids this summer. “I haven’t done much with art,” she admits, except for greeting cards that she takes to the farmers’ market, and the farm logo. She has done a lot with MOFGA, having served on the Board in the past and now as an active member of the Waldo County chapter.

Sumner and Paula got their first sheep, four ewes, in 1990, in Orrington, where they lived for seven years. They’d bought the house and 20 acres with enough room to raise chickens. They had horses and a few sheep to eat the grass. Sumner worked on a dairy farm for a while when he became interested in grass farming using pastures – a practice his employer did not use. Their own farm “was too small, the soil was clay and it wasn’t good for much. We looked for a bigger one everywhere from Vermont to Orrington. Most farms for sale didn’t have good soil and the woodlots were stripped off. We found this one by chance. We were lucky: 120 acres, nearly half open, and the woodlot hadn’t been cut over. The old fellow who owned it was too much of a miser to let anyone make money on it and too busy to do it himself.”

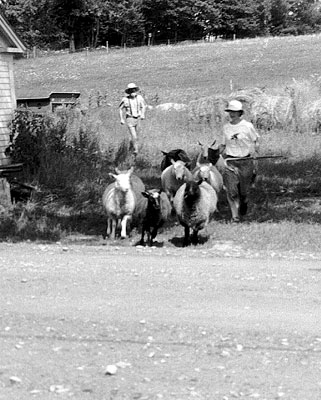

|

| Paula urges sheep to their new pasture – trailed by Pippin, the Australian Sheep Dog, who missed the photo op. Lamb photo. |

Sumner, who has a degree in wildlife biology and a master’s in sustainable agriculture, explains how grass farming affects not only the health of the animals, but that of human consumers. “Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) is known to be an important anti-cancer factor. It creates more muscle than fat and changes the way the body metabolizes fat,” he points out. “It only forms when animals graze green pastures. It’s higher in vitamins A and E, fat-soluble vitamins. It [also] turns out that all the horror stories about beef contaminated with [the virulent, 0157:H7 form of] E. coli [don’t happen with grass-fed animals]” because grass feeding creates a pH in the rumen that is unfavorable for the pathogen. In grain-fed animals, E. coli, which occurs naturally in beef animals, becomes acid-resistant, Sumner says. If meat is contaminated during processing, the human stomach, which is highly acidic, cannot deal with it. “They’ve actually found that being fed hay for just 10 days after a grain feedlot diet would clean animals of the acid resistant strain, but it’s not profitable. Animals coming off green grass pasture don’t have those problems.” The more mature animals that the Robertses sell have been on hay all winter, but are not slaughtered until July, when they’ve grazed for many weeks on good grass. Animals that are slaughtered in October and November haven’t been fed any grain since they were small calves.

Building Fertility

The fields at Meadowsweet, now luxuriant in red clover, had been hayed very hard or had been allowed to grow up to 6-foot-tall meadowsweet – hence the farm’s name. “It’s taken a lot of work to get them to look like this,” Sumner says. “Bush hogging, grazing, lime, fertilizer, manure. This clover is actually where I spread all last year’s cow manure when we cleaned out the barn.

|

| Paula and Sumner move sheep outdoors. Lamb photo. |

“The first year I spread a lot of manure and didn’t see much response, the soil life was so low. We still have a long way to go to get them as productive as we’d like.” Two 25- to 30-acre parcels, a rolling upland on one side of the road, a gentle meadow on the other, are devoted to pasture. Sumner buys all his hay in big round bales from local farmers. He rolls these out across the snow for bigger cattle that live outside all winter, a spread that gives all of them room to eat without fighting, he says. They have protection from the wind against the woodlot on the north and a brushline on the west. If the wind comes up from the southeast, he moves them across the farm to another shelter. They don’t need a roof. “Rolling spreads the waste hay across the field so I don’t have to spread it in summer. The grass comes in wonderfully.”

While Meadowsweet’s vegetable garden is MOFGA-certified organic, the animals aren’t, because “we buy our calves from dairy farmers and they’d have to have been raised organically, too,” says Paula. Also, they buy hay that is not organic, and they treat their lambs to prevent coccidiosis. Inside a big greenhouse – an unlikely clinic on a warm August afternoon – several dozen spring lambs bleat their protests and anxieties as Sumner and Paula herd them by fours and fives though moveable pens, chutes and gates to treat them for a sheep variety of coccidiosis. Young cousin Kellen Leon Atkins, vacationing from New Jersey, records their number tags and dosages.

|

| Sheep are moved across the road; the hillside pasture is in the background. Lamb photo. |

“We’re giving them a time-release bolus,” Sumner explains as he reaches out with his old-fashioned shepherd’s crook to snag a straying ram. “It’s not organic, but there isn’t an effective organic one. We’ve never had a lamb die of coccidiosis, but they could if it goes untreated.” Even a mild case impedes normal growth, he says. “Since we direct market all of our lambs in the fall, we need to keep them growing at a reasonable rate of speed.” (Ed. note: According to Eric Sideman, MOFGA’s director of technical services, organic growers who do not want to use such boluses can minimize problems with coccidiosis by using many of the other techniques that the Robertses do: using reasonable stocking rates, avoiding damp bedding and avoiding stress in the animals.) The young rams among the flock practice butting and try out their deeper vocal register, illustrating another growth-enhancing practice at Meadowsweet. “They’re a bit aggressive and lively,” Sumner adds, “because we don’t castrate ram lambs that we’re going to be selling at six months in the early fall. They grow faster and leaner that way.

“It’s too warm in here,” he continues. “They’ve just come in from the pasture and will go right back out to one that’s only been grazed by cattle this summer. It should be clean and free from coccidiosis.” Sheep, cattle and poultry are affected by different kinds of the disease, which do not pass from one type of animal to another, he points out, though the risk of infection of any kind is minimized by the Robertses’ intensive rotational grazing program. As the grass comes on in the spring, cattle go first to a hillside pasture, where they are moved regularly among small, polywire enclosures containing enough grass for one day’s grazing. By the time they return to that section, the grass has grown sufficiently for another day. After several rotations, they’ve consumed everything cattle want to eat, and the sheep move in with their closer grazing habits. Meanwhile, the sheep have been in a separate rotation on lower ground across the road, now dry enough not to be damaged by the heavier cattle, and the two sets of animals exchange pastures.

When is a Greenhouse Not a Greenhouse?

The classic 1880s Maine farm that the Robertses bought in 1994 has a cavernous barn attached to the two-story house, but their sheep and cattle don’t set foot in it. Like any century-old barn, it’s dark, damp and probably harbors more than a few pathogens. The 30- x 100-foot greenhouse has been, from the beginning, a “solar barn,” an unfamiliar concept to many. Sumner and Paula find themselves calling it a greenhouse for the sake of simplicity. A Harnois model from Greenhouse Suppliers in Brewer, it is designed to shed snow readily in northern climates, its double plastic covering inflated by a blower. It’s not heated, the ends are closed with shade cloth, so it has good air circulation, and the sides can be rolled up in warm weather. “Bright light and fresh air are much better for the animals,” Paula says. Calves are raised there in winter, it’s a lambing barn in the spring, and occasionally it’s a clinic.

|

|

The Robertses and cousin Kellen tend sheep in the “solar barn.” Lamb photo. |

The Meadowsweet flock last August comprised 45 ewes, 74 lambs and two rams, mostly North Country Cheviots, a few Dorsets, Coopworths and Jacobs. “One of the things I found really interesting,” Paula notes, “is that the Jacob cross show fewer signs of parasites. The old-fashioned breed seems more hardy and disease resistant.” All the lambs are sold except for those that are kept as replacement ewes and to continue increasing the flock’s numbers. The Robertses purchase day-old beef/dairy cross calves in winter, to be sold for beef. In 2000, they raised sixteen. “I usually sell a couple of heifers at auction, the ones we don’t need for market,” Sumner says. “Being a dairy cross, they make a good family milk cow where top production isn’t needed. We breed some of them, and when they calve and have too much milk for one calf, we put an extra calf on them to be raised for veal.” The calves purchased in winter when no fresh milk is available are started on milk replacer. “We’re hoping to get some extra whole milk from a local dairy. If we could get it consistently, it would be better. We believe that animals, like people, are healthier when they eat what they’re evolved to eat.”

Paula expands on the process: “Calves raised on milk replacer, usually in late fall or winter or early spring, go from milk replacer to grain before they go on grass. They need the supplementation because they haven’t had whole milk. Naturally a calf raised on its mother for six months is getting grass through her, but with milk replacement they get weaned in six weeks. They just don’t do very well if they go from six weeks just to grass. Our calves that were born here last summer and raised on milk and grass did much better than calves we started on milk replacer and grain.” Last summer there were three mothers, heifers they had kept and bred. One was a Lineback, a rare dairy breed that is typically brown with a white line down the back. This one was a color variant, white with dark ear tips, nose and feet. Her calf, sired by an Angus bull, had the typical Lineback coloring. The other two mothers were Hereford/Holstein crosses, one black with a white face and the other brindle. Each was feeding her own and a couple of orphan calves. The Hereford/Holsteins were purchased from a dairy farmer, who would otherwise have sent the unwanted calves to auction.

|

| Meadowsweet’s farm buildings are classic 19th century. Lamb photo. |

Meadowsweet Marketing

Meadowsweet Farm’s principal business is marketing grass-fed beef, veal, lamb and a few chickens directly to retail customers at the farm and at the Belfast and Orono farmers’ markets. It is slaughtered, packaged and frozen at Jason’s Butcher Shop in Albion or at Curtis’s in Waldoboro. Legally, Sumner can slaughter some only for their own use. Last year Paula charged $2 a pound for chicken, which gave her enough profit to pay for the cost of raising a few for themselves. “It’s an expensive way to pay for our meat,” she admits, citing the cost of the chicks, their transportation, and grain. “Some people are thrilled to buy chickens from me at that price. Others would be horrified because they can get it at the supermarket for 50 cents. They don’t think of the difference in flavor or the quality of life for the chicken or the impact on the environment. Or where the grain comes from, what else [the chicken is] fed, or the medication and hormones necessary to keep it alive [in the agribiz environment].”

“I was wondering,” Sumner puts in, tongue in cheek, “how much it would be worth to me to pay Paula to raise chickens for their fertilizer value. Instead of polluting Chesapeake Bay, hers have fertilized half an acre of pasture, which is growing beautifully right now.”

Going back to marketing, Sumner says he’s envious of people who have a greater demand than they have supply. “We’re not there yet. One of our challenges is to find the people who know that grass-fed meat is healthier. I want to find out how to get it to them. We’ve had calls from people in different parts of the country, but getting it to them would be too expensive. There must be people in Maine who would be happy to drive a couple of hours to come here to get a freezer full of beef. And again, I’m not eager to look for a national mail order business. People should be eating what grows locally. It’s not that shipping is so expensive. It’s not much more than loading two animals at a time to drive to Albion. It cost me $30 per animal last year, and only cost $40 per animal to send some extra ones to Pennsylvania, but that’s because someone put together a whole truckload. But [diesel trucking] is polluting. If we could have someone slaughter right here it would be better, less stressful, than getting them into a strange truck, even just for a 45-minute drive.”

While meat is the major item on the Meadowsweet farmers’ market stand, Sumner and Paula also sell sheepskins and blankets made from fleeces they send to the MacAusland Woollen Mill in Prince Edward Island – a rare, welcome find in this day of polar fleece everything.

The seedlings that Paula raises in a small greenhouse in their 100- x 75-foot organic garden, as well as cut flowers, surplus lettuce and a few other vegetables, go to market, although the garden is primarily for their own use. They’re considering raising melons and peppers for market well.

And There are Horses

Horses are still part of Paula and Sumner’s lives. Jason, a 31-year-old gelding that once belonged to Paula’s mother; Truce, a 16-year-old Percheron/ Morgan mare; her daughter, Sophie, whose father is a Morgan; and Joe, an elderly Percheron draft horse, live in the basement of the old barn, along with the chickens (when they want to come inside). The huge loft is stuffed with the winter’s supply of hay, and the main floor is filled with straw. Many more horses inhabit Sumner’s world. In fact, a good part of the farm’s income comes from the horseshoeing business he started 10 years ago. He studied at the Eastern School of Farriery in Virginia and traveled with a couple of other farriers before going on his own. Waldo County is home to a good many “backyard” and trail riding horses. In Brooks and Belfast, horse clubs sponsor low pressure horse shows where children and teenagers compete, and even a few serious horse owners travel to compete in dressage and the like. “There are a few work horses,” Sumner says, “but they’re not much of my business. It takes a lot more work to shoe a draft horse, so I charge more. That means that the old timers with draft horses are not going to pay my fee, so they do it themselves.” His own two draft horse crosses and old Joe, whom they bought to help train them, are more pets than workers. The woodlot maintenance they were originally used for has given way to long hours spent raising livestock. (They are hoping to have a MOFGA apprentice to help with the work load this summer.)

Though they both enjoy riding, Paula and Sumner seldom find time to get to it. What comes first is their devotion to the business of promoting the health of people and animals. As Paula puts it: “We feel very strongly about having the animals on pasture, improving and rotating pastures, and [all of us] living in the natural environment as much as possible.”

About the author: Jane Lamb is a long-time feature writer for The MOF&G.