|

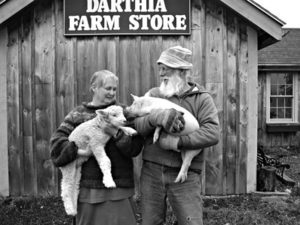

| Bill and Cynthia Thayer and two new friends pose in front of the Darthia Farm Store. Erin James photo. |

By Rhonda Houston

“Well, it’s pretty exhausting work,” say Bill and Cynthia Thayer after a moment of thought. A few days after I sat down with the Thayers of Darthia Farm in Gouldsboro, I can’t quite remember if they were referring to the vegetable patch, the Haflinger horses, the wood lot, the spinning and weaving, the sheep, the bagpipes, the funk band or the nearly 200 apprentices they have hosted over the last 25 years.

Regardless, after a morning of sitting around a table that’s big enough to hold a slew of summer help and those who keep returning, I see no sign of exhaustion in these perennial MOFGA farmers. Cynthia is taking a break from packing for her trip to Ireland with the Wednesday Spinners, a group she has been active with since its inception, and Bill is giving the horses a break from the woodlot to explain to me how he and Cynthia came to farming and what motivated them to play teacher, friend and surrogate parents to so many young people over the years. The story is never simple, never typical, but holds a common thread for many farmers.

It’s hard to find a farmer these days who actually grew up on a farm. Bill grew up in Massachusetts to become an insurance salesman, owning his own business. “I never liked that relationship that I had where people were prospective customers,” says Bill of the insurance trade. “I wanted to have real relationships, and so I grew to kind of despise the business, which is probably unfair,” he recalls, acknowledging that he and Cynthia have a lot of insurance. “Three of my customers were dairy farmers, the only farms in town, and they happened to be my favorite customers.” Those farmers, Bill says, probably had something to do with the abrupt changes he made in his life. Before farming, however, Bill returned to school to become a special education teacher – and that’s how he met Cynthia.

Cynthia, the daughter of an opera singer and a clothing designer, grew up in Nova Scotia. “Where I grew up, farming was something poor people did,” says Cynthia. “But, I always loved to play in the dirt.” Cynthia left Canada for Massachusetts to become an English and theater teacher.

|

| Building a hoop house is just one of the experiences that apprentices may have at Darthia Farm. Cynthia Thayer photo. |

Farm Animals: Better than Bureaucrats

In 1976, the Thayers found a farm for sale in Downeast Magazine. “Though I loved teaching, I hated what I saw in the public education system,” says Cynthia. “Dealing with sheep and chickens, rather than bureaucrats, just seemed like a good idea.” They left their jobs, bought the 150-acre farm on the ocean, and have been pulling weeds, digging holes, raising animals and sharing all they know with hopeful apprentices ever since. Selling Bill’s insurance business gave the couple seed money to buy the farm.

The unusual farm name had a spirituous origin. “One night almost 30 years ago over a glass or two of wine,” says Cynthia, “I called him ‘Darlie’ and he called me ‘Thia,’ and there you have it.

“We moved here with two goats, two sheep, two horses and a bunch of chickens,” begins Cynthia. “Of course, we had no cleared land. We worked from early in the morning to late in the evening, and then we’d go inside and read every book we could find on sheep and goats and vegetables, and then we’d get up and do it again.”

Regarding the horses, Bill explains that they “do whatever you want them to do. It’s just a matter of you being able to make them comfortable. The Haflinger’s are a product today of my mistakes.” The Thayers decided early on that they didn’t want Darthia run by a lot of machinery. Other local farmers, such as Bill’s good friend Paul Birdsall of Horsepower Farm in Penobscot, were using draft horses for farming and woods work. After working with ponies for several years, Bill decided to purchase the larger Haflingers.

“I made the stupid mistake of buying two colts and trying to train them together,” he laughs. With two broken legs behind him, Bill’s advice on working horses is a bit tongue in cheek. “I attempted to learn very foolishly, because I didn’t have anybody to teach me, and Paul (Birdsall) was just too far away.” After nearly 20 years with the troublesome colts, Bill thinks he might have it down. While he was conquering the art of horsemanship, Cynthia was cultivating her spinning and weaving skills. “Almost every apprentice who comes through here learns how to spin,” says Cynthia. Their sturdy flock of eight provides Cynthia and the apprentices with plenty of wool.

|

| The Thayers’ youngest “apprentice,” John, is actually the son of Darthia’s assistant managers. Cynthia Thayer photo. |

Finding local markets was a challenge in the early years. The Thayers focused on selling meat to local retail outlets. Darthia Farm, perhaps best known today for its elaborate farm store that sells everything from veggies to hand-spun wool, and for its unique mail-order catalog, started with a small farmstand. As more customers started coming to the farm and seeing how their food was being produced, the farm stand grew into the farm store, and buying from Darthia became an experience rather than an errand. Once customers have been to the farm store, they’re likely to receive a catalog from the Thayers. Twenty percent of those who receive the catalog purchase from it. Such response is rare in catalog sales, but it’s an example of the kind of customers the Thayers attract and keep.

The farm store, the catalog, and the rest of Darthia Farm have had many more hands involved than Bill and Cynthia’s – nearly 200 sets of hands of all ages and walks of life. The Thayers may have left the public school system, but their passion for teaching didn’t leave them.

Apprenticeship Training Grounds

Their first attempt at hosting an apprentice came that first summer. “Oh, we just blew it with him,” laughs Bill. The apprentice, one of Cynthia’s former students who was having a bit of trouble, came to Gouldsboro in the spring but was gone before summer. Though the young man was not cut out for farming, this experience did not stop the Thayers from looking for other apprentices. Through MOFGA’s new apprenticeship program (started by Chellie Pingree and later run by the Thayers), the couple found two young women from College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor. Those women, and subsequent apprentices in those first years, had different experiences than those who work at Darthia today.

“For the first several years, our apprentices worked when we worked,” says Cynthia. “But then we got old, and I started writing and playing the bagpipes, and Bill pulled his drum set out of the attic, and we backed off from farming a bit. You can’t ask apprentices to work more than you’re working.” Apprentices at Darthia today generally work from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., with Saturday afternoons and Sundays off. “We’ve talked about how we’re misrepresenting farming to the apprentices at this point,” says Bill, but the apprentices keep coming, and some don’t seem to leave.

“There are 15 former apprentices living within 20 miles of us.” Bill explains that the apprentices aren’t much competition. “They’ve learned from being here that they don’t want to farm,” laughs Cynthia – but that isn’t exactly true. Many of the apprentices are gardening, spinning, weaving or doing carpentry, skills they learned from Darthia. “The guys that went on to be carpenters are far better carpenters than I’ll ever be,” Bill points out. The Thayers have also noticed the matchmaking capabilities of their farm, as many former apprentices are married to one another. Though they don’t advertise the farm as such, the hours spent pulling weeds and tending chickens seems to have a cupid affect on young farmers. “Whether they go on to be farmers or not, they finish the apprenticeship realizing that they can take care of themselves in a number of ways, and that’s very empowering for young people.”

|

| Whether at Darthia or at the Common Ground Country Fair, where he volunteers many hours, Bill Thayer can often be seen driving a wagon load of visitors. Cynthia Thayer photo. |

The Thayers see similar qualities in apprentices who have gone on to become successful farmers. “You have to be devoted to this lifestyle, really devoted,” says Cynthia. “And crazed, you have to be crazed.” While most of the apprentices who have walked across the front porch of Darthia farm may have had dreams of becoming farmers, Bill and Cynthia hope all of them left knowing they could change dreams midstream. “I think it’s really scary that young people at the age of 21 or 22 are worried about making the wrong decision,” says Cynthia. “They’ve been fed [the idea] by someone that unless they make a decision early in their lives, they’re going to fail.” Whether the apprentices have gone on to farm or not, they return to Darthia often. “They keep coming back, and with more kids,” says Bill. “It’s like having a second set of grandchildren.”

“I think our ex-apprentices own the town of Gouldsboro,” Cynthia laughs.

After 25 years with apprentices, the Thayers have no plans for slowing down. They have apprentices this summer and, in March, were looking for a full-time assistant to help coordinate all aspects of the farm. “We have five children between us, and none of their interests lie here,” says Bill. As their interests move beyond the farm, the Thayers are looking for a person or couple to take the next step beyond an apprenticeship and settle into a more committed role. With the offering of a cottage on the ocean and a lifestyle that, according to Bill, is guaranteed to make you healthier, the Thayers probably will have no problem filling this position.

The summer apprentices had already started arriving at the time of this interview on a bone-chilling March afternoon. Amanda Caron, a young woman from New Hampshire, found out about the Thayers through their website and decided to spend the spring helping Darthia farm wake from its winter nap. “I’m interested in farming because of the idea that it’s an occupation that’s not just a job, but a job you can be dedicated and passionate about,” explains Amanda. She didn’t gush on about wanting to be a farmer someday; instead she described a goal that the Thayers say is one of the best goals to have when coming to Darthia or any apprenticeship: “I would like to have some element of self-sufficiency.” Asked what she would tell the other, soon-to-arrive apprentices, she laughed. “I guess to keep a sense of humor, especially with Bill, and stay flexible and laid back.” The Thayers quickly agreed with keeping a sense of humor, always, and of course staying flexible, but they hesitated on Amanda’s advice to stay laid back. “We had one apprentice who was a great kid, but when he was supposed to be weeding he’d look at the weed, philosophize about the weed and forget to pull the weed out.”

For farmers who are considering hosting apprentices, Cynthia says, “You teach them what you know. As a farmer, you’re just providing a vehicle for learning.” The vehicle, according to the Thayers, is as meaningful if you’re a farmer just starting out or one getting ready to retire. The lessons are simple, the time is invaluable. “The relationships we build with apprentices,” muses Bill, “that’s what’s really important.”

|

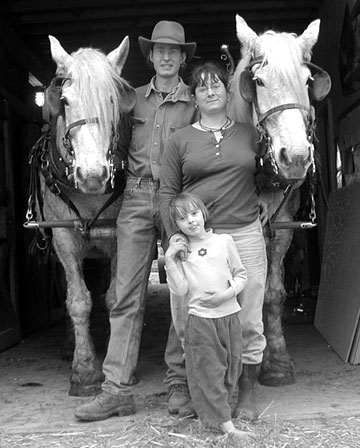

| Michael Glos is a former Darthia Farm apprentice who, with his wife Karma and their daughter, Rosie, have a successful farm in New York where they raise vegetables, herbs, pastured poultry and more. Photo by 5-year-old Jasper Pitney. |

An Apprenticeship Success Story

When the Thayers list you as one of the best apprentices they’ve had in their 25 years of hosting hopeful farmers, it may be time to put down the shuffle-hoe and pat yourself on the back. Former Darthia apprentice Michael Glos and his wife Karma receive the Thayers’ admiration, a compliment in the highest regard.

“Michael was one of the most disciplined apprentices we ever had,” Bill recalls. Bill credits this discipline, which could be seen in everything Michael attempted – including a diligent hour a day practice schedule for his trumpet – with his current success in farming. “He would jump right into something and give it everything he had,” says Bill.

Michael didn’t exactly jump right into farming. A scientific mind, a quality the Thayers also noted, brought Michael, as well as Karma, to jobs with the Forest Service in the Northwest. Then they decided to head back east and start a farm. Michael, armed with his experience at the Thayers, and Karma, with her own apprenticing background, found a rocky hillside in Berkshire, New York, to try their hand at farming. That same scientific mind kept the Gloses out of debt and on track to make their hillside a profitable enterprise. After seven years of operating Kingbird Farm, Michael and Karma have created a small, diverse, organic, horse-powered farm that mirrors the Thayers in many ways, but is, of course, a creature of its own kind.

Kingbird Farm focuses on diversity, a quality Michael learned from the Thayers. With NOFA-NY certified organic meats, produce, herbs and eggs, the Gloses have found year-round markets in a typically seasonal business. They do some on-farm selling but focus much of their energy on the Ithaca Farmers’ Market, where Karma gets away from the farm. “We just don’t have a lot of outside interests,” explains Karma. “Most of our other interests are part of farming.” And this is the way they want it.

Karma worked full time on the farm from the beginning, while Michael took a job at Cornell University and focused his weekends on the farm. Karma also was quite occupied after the birth of their daughter Rosie. “Having a child in our first year of farming was one of the best things, because it changed the pace of everything,” says Karma.

|

They experimented with lots of different techniques while slowly building their farm infrastructure. “We did everything slowly, because we didn’t want to get in over our heads,” explains Michael. “A lot of people who go into farming aren’t thinking of it as a business,” and this is where Michael sees many farms fail. “We gave ourselves five years to make the farm profitable,” and in the meantime Michael kept a full-time job to support the growing farm and family. “The things that made us the most successful are that we went slow and didn’t go into debt,” says Karma. “Karma is what made this farm what it is by being here while I worked off-farm in the early years,” Michael adds. He scaled back his off-farm employment gradually as the farm grew and still works for NOFA-NY part time.

The Gloses also stress the need for diversity. “We found things that grew well and grew them,” says Michael. Over the years they pared down the offerings to vegetables that grow well on their hillside and that they both enjoyed cultivating. That diversity extends to their meat offerings as well – Karma’s specialty. “If Karma wasn’t here, all the animals would die,” Michael offers, though he’s quick to point out that the farm may be broke if he weren’t around.

With their own farm slowly establishing, the Gloses decided to invite apprentices to lend a hand. “I never think I have anything to offer until I sit down and start talking to a new apprentice,” laughs Karma. While Michael looks back fondly on his time at Darthia Farm, Karma’s apprenticeship elsewhere was monotonous. She was seen more as cheap labor and less as a student. Thus, “I was hesitant to get an apprentice until we had a lot to offer them,” says Karma.

Michael, on the other hand, says, “When I was at the Thayers’, I learned so much so quickly. Of course, I worked a lot harder for the Thayers than I do for myself.” This may be a bit of an exaggeration, as the Gloses have been featured in local papers frequently, have written several papers themselves, and Michael has been active with NOFA-NY’s Public Seed Initiative.

The Public Seed Initiative, a collaboration of NOFA-NY, Cornell University, Oregon Tilth and the USDA, brought Michael and Karma to the 2002 Common Ground Country Fair, as Michael informed Maine’s farmers of the work to bring the right seed to the right farmer. The project has three components: seed trials, seed cleaning and breeding workshops. The workshops teach growers how to adapt the right varieties to their farms. As organic growers are introduced to new varieties, many of which were sitting dormant on laboratory shelves, the Initiative and Michael are making a lasting difference.

The Gloses are preparing to welcome their second apprentice from an agricultural university in France. “We have knowledge to give them now,” says Karma. “They won’t just be used for weeding.”

|

Recipes for Successful Farms: The Success of Diversity

We believe that diversity is the foundation of short- and long-term success of any farm. This means having a mix that spreads out the work as well as the risk. I would prefer to be planting something different every month rather than trying to get all my crops in in May and harvested in September. Our gross income distribution now is 55% from meat and eggs; 25% from veggies and herbs; and 20% from value added products, feed resales (we buy and resell bagged organic feed) and grants (SARE, USDA, Soil and Water Conservation District). Our actual, net income is probably more like 40% from meat and eggs; 40% from veggies and herbs; and 20% from other. We make less per dollar with the meat, because we have more money invested in it. Most of what we have in the herbs and veggies is our time (which we need to get paid for). Part of our diversity includes me bringing in some money by working on the Public Seed Initiative. We don’t like to have our eggs all in one basket!

– Michael Glos

For more information about Kingbird Farm, see www.kingbirdfarm.com.

A Fabulous Lifestyle

Farming and writing make a great combination, because much of my writing I can do in the winter. I have a yurt down by the water that I use half days the rest of the year. Writing novels needs more time than just the winter months. If you can get some other time regularly, it will work. If you’re writing articles or nonfiction, I think farming and writing can be a great marriage.

My writing money, the mail order, and money that we have from previous businesses enable us to make it financially. Farming, unfortunately, is not very rewarding financially. The rewards need to come in the form of a fabulous lifestyle. Although we don’t have off-farm jobs, we do other things. I do a lot of teaching of writing and teach in other areas. Bill sells pulp wood. We try to take a farm product as far as possible – i.e., value added. We make jams, jellies and herbal vinegars. We mix and wash salad greens for our customers and for Mama’s Boy Bistro in Winter Harbor. About half of our farm income comes from the mail order business, which we do in the fall for the holiday season. Of the seasonal farm income, probably well over half comes from the value added items, such as salad greens, yarn, jams and pesto. This year we’re doing free-range chickens, which bring in a fair amount. Just selling plain carrots doesn’t bring in enough money. Unfortunately, most Americans are after cheap food and spend far less of a percentage of their income on food than people do anywhere else in the world.

Expenses for farming are very high. Although we pay only a stipend to the apprentices, we do pay for their food, phone and electricity – which can be quite a bit when you have four apprentices.

– Cynthia Thayer

Cynthia’s books, which have a strong Maine flavor, are A Certain Slant of Light and Strong for Potatoes, both published by St. Martin’s Press, N.Y. Cold Crossing is being marketed by her agent. For more information about Darthia Farm, visit www.darthiafarm.com.