by Larry Lack

Bonnie and Arnold Pearlman have been farming organically in Jonesport for 34 years. They can’t recall what year they were first certified by MOFGA, but Arnold says they were “among the very first.”

The Pearlmans found their 20 acres of woods and blueberry barrens in the mostly unpopulated interior of the Jonesport peninsula in 1969. Originally from Philadelphia, Arnold worked as a VISTA volunteer in Detroit’s black ghetto in the late 1960s. He met Bonnie, who was raised in New York City, when she came to visit a friend in Detroit. At the time, both were in their early twenties.

Soon after meeting they came across an ad in the Boston Globe for a $300, 5-acre piece of land in Milbridge. In midwinter they drove their VW bug to check out land in Maine. They decided against the $300 parcel in Milbridge, but located the 20 acres that became Crossroads Farm and bought it instead – for 800 dollars.

Building a Life

Their first home on the isolated, rough and rugged land they had selected was a mail van. They cleared land and built the home in which they still live, and cleared land for their first gardens and planted crops, initially just to feed themselves. “We did everything at once in those first years,” Arnold says. “We had to.”

|

| The Pearlmans built their home themselves and are still off the grid, using, instead, wind and solar power. Larry Lack photo. |

When they moved to Maine, the Pearlmans had no practical experience with gardening, carpentry, mechanics or other farm and homestead skills. They knew they wanted to grow food in harmony with nature, avoiding chemicals, which, Arnold says, “we wouldn’t have wanted on our land or our food even if we could have afforded them.” Instead of using chemicals, the Pearlmans control weeds and insect problems by careful crop rotation, companion planting, cultivation and continual rounds of manual labor.

To this day their wood-heated home remains unconnected to Bangor Hydro’s power lines. Power for lights and for pumping water from their hand-dug well to do laundry is generated by a windmill and several solar panels built and installed by Arnold.

Most of the cars and trucks parked at the farm are used for on-farm ferrying of crops and soil amendments, or else as sources of parts. “When it comes to vehicles, we’re major recyclers,” says Arnold, who does nearly all his own mechanical work.

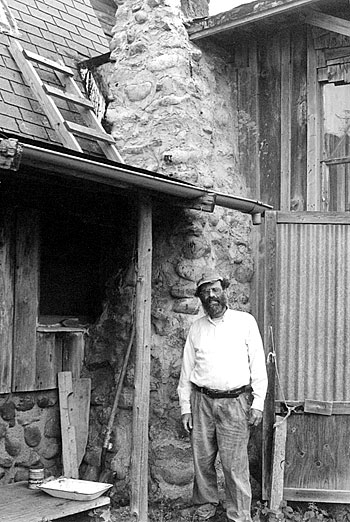

|

| Arnold Pearlman stands next to the stone chimney at his home. Larry Lack photo. |

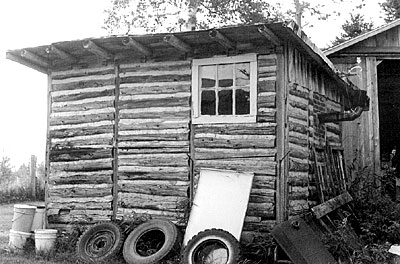

The house, barn and sheds of Crossroads Farm, mostly constructed of hand-hewn logs and boards from the farm, are simple, graceful and utilitarian. Some of their features and details, including cabinets, drawers and door latches, are reminiscent of traditional Amish craftsmanship. Arnold recalls that “we learned how to do things as we worked, drawing on the talent we have of being able to understand how things are made and how they work by looking at them.”

Diverse Crops from Humus-Rich Soils

As the first years passed, the Pearlmans planted an apple orchard, which now contains about 300 trees, and expanded their gardens into the woods and impoverished blueberry barrens of the farm. And as they brought land into production, relatively poor soils were conditioned and fertilized with manure cleaned out of old barns; with fish wastes and with seaweed from the nearby shores; and with wood bark and peat moss. Arnold explains that “we’ve worked to incorporate organic matter into the land, with the emphasis on fiber and carbon rather than quick nitrogen, so as to gradually convert poor soils into rich humus.” Building balanced, fertile soil, he says, “is an unending job” – but it’s one that seems to suit him as he forks seaweed from a farm truck onto asparagus beds in one of the large gardens at Crossroads Farm that together total about 6 acres.

The Pearlmans produce and market a myriad of diverse crops. Scores of different greens go into the salad mixes that are a major segment of the farm’s commercial output. In the week of my visit, the farm’s salad mixes included a dozen different mustards, a dozen lettuces, plus several kinds of kale and edible flowers. Beans, peas, onions, beets, carrots, squash, tomatoes, potatoes and herbs are among the other crops they grow and sell. Jerusalem artichokes are a specialty – about 800 pounds a year are marketed, mostly to a Maine wholesaler.

|

| An outbuilding made of logs from the Jonesboro property. Larry Lack photo. |

The orchard included as many as 80 apple varieties in years past, but now only about two dozen varieties are grown. Scab resistant ‘Liberties’ account for about a third of the trees, most of which are standards, as dwarf and semi-dwarf trees don’t seem to thrive here, according to Arnold. Although he and Bonnie keep some apples for winter use, most of the orchard crop is processed into organic cider. The orchard is protected from the hungry local population of deer and moose with fencing featuring homemade gates and posts from the farm’s woodlands.

Except for a few months when Arnold worked off-farm as a carpenter, the Pearlmans have made their living entirely from their farm for all of the 34 years that they have lived there. Their crops are marketed almost entirely in eastern Maine. At first, farmgate sales were their mainstay, and they still sell to dozens of neighbors and visitors who drive the long gravel road to their farm. But wholesale buyers, plus stores, restaurants and inns in Machias, Ellsworth, Mt. Desert Island and Blue Hill now buy much of what’s produced at Crossroads Farm. An employee delivers the harvest to these markets so that Arnold and Bonnie can focus on the work of farming .

|

| Rustic and modern wheelbarrows create a neat, artistic scene at Crossroads Farm. Larry Lack photo. |

The challenges encountered in managing so much land and so many different crops require the steady application of carefully planned, well-organized physical work. Much of the field work that the Pearlmans and their seasonal employees do at Crossroads Farm is accomplished with hand tools, although gas powered tillers, a tractor, a chisel point plow and a subsoiler are also used, and in very dry times water is pumped from a pond with a gasoline pump to irrigate some of the fields.

Except for very modest use of Reemay, no plastics are used on the fields of Crossroads Farm, despite the short growing season with which Bonnie and Arnold must cope. “We hate plastic, and we tend to concentrate on crops that can do well here without a lot of babying,” Arnold says. “You won’t see plasticulture here.”

Beginning in midsummer, harvesting consumes most of Bonnie and Arnold’s daylight hours from Sunday through Wednesday every week. Weeding, tilling and cultivating, fertilizing and other garden chores are tackled on Thursdays, Fridays, or whenever time can be found. Insect problems, including frequent infestations of Colorado potato beetle and striped cucumber beetle, are handled by hours of hand picking in hundreds of feet of crop rows. Dealing with problem weeds, including coarse grasses, dandelions, lambsquarter and the tenacious, difficult to manage weed called galinsoga, which arrived in Washington County a few years ago, also requires relentless effort.

During my visit to the farm in early August, Bonnie was weeding onions with a young employee, Kirie. Bonnie left answering my questions mostly to Arnold and, when Kirie paused to answer some questions I had put to her, Bonnie gently urged her back to the work at hand with a good-natured reminder: “Weed, Kirie – you know, you can answer questions and weed at the same time.”

Despite their long association with MOFGA, the Pearlmans have never been to the Common Ground Fair. Arnold explains that “it happens right in the middle of our busiest weeks at the farm. And going would keep us from observing our sabbath on the Saturday of the fair.”

Throughout the warm months of the year, with help from up to a half dozen employees – neighbors and summer visitors to Washington County – Bonnie and Arnold work almost continuously from dawn to dusk – except for Saturday, the Jewish shabbos (sabbath), when they do no work at all.

Rest and Reflection

“On Saturdays we take a complete rest. We study the Torah then, and go for a good walk,” Arnold says, adding, “We love the hard work we do, but like a lot of other people, we used to be addicted to work, to activity. It’s really hard at first to accept a day of nothing but deep appreciation and no worry. But after a while you find that when shabbos comes you leave a big burden behind, and you look forward to that all week. Of course we also learn all week long from the farm and the work we do here.” Smiling, he suggests that “a little bag of coriander seed probably contains more information than all the computers in the world, don’t you think?”

Both Arnold and Bonnie were raised in secular, nonpracticing Jewish families, and when they started farming they were not religious themselves. But despite their location in Downeast Maine, where almost no other Jews live, they have become deeply religious, observant Jews over the years that they have lived in Jonesport. They use their Hebrew names – Avraham and Dinah Bracha – with each other and when they meet and talk with other Jews. “We work here as servants of God,” says Arnold, “growing food for ourselves and others. In the Jewish tradition farming is a very respected calling, because the farmer is privileged to see the hand of God every day.”

When they began farming, he and Bonnie were already vegetarians for health and economic reasons. They now keep kosher, and abstain from eggs as well as meat. “We never wanted animals,” Arnold explains. “We thought it was enough of a challenge to feed ourselves.”

During his 34 years in Maine, Arnold has become a serious Talmudic scholar, a philosophic farmer who applies the ethical and spiritual principles of Judaism to his life and work. In winter he and Bonnie travel to Long Island for religious assemblies, and Arnold participates in a program of Talmudic study and interpretation over the telephone.

“We aren’t concerned with accumulating things,” Arnold says. “God takes care of us and gives us what we need. Once in a while, when we’re selling our crops, someone says they think our prices are too high. Then we ask them, ‘What do you think this is worth?’ and we sell to them for whatever price they think is fair.”

In spite of the tragic loss of one of their three children, a daughter buried at the farm who died 25 years ago at the age of seven months, felled by SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome), Arnold says farm life has blessed his family throughout nearly all of the years they have spent in Jonesport’s isolated puckabrush. He and Bonnie hear regularly from their grandchildren and the two adult children they raised here, a son who lives in New Jersey and a daughter in Ireland.

But the farm and the work of producing an amazing bounty of organic food are the root of the happiness that Bonnie and Arnold pass on to customers, friends and others who connect with them. “Believing Jews are commanded by our law to be happy,” Arnold says, “and to cherish their lives and enjoy being alive … In a sense we think we’re actually being very selfish, because what we do here makes us happy – working this farm, growing and sharing good food. We’re thankful for every day of the life we have here.”

About the author: Larry Lack is an organic farm inspector and a writer. He lives in St. Andrews, New Brunswick.